Eighty tonnes in a single scoop: Mega-mining iron ore

- Published

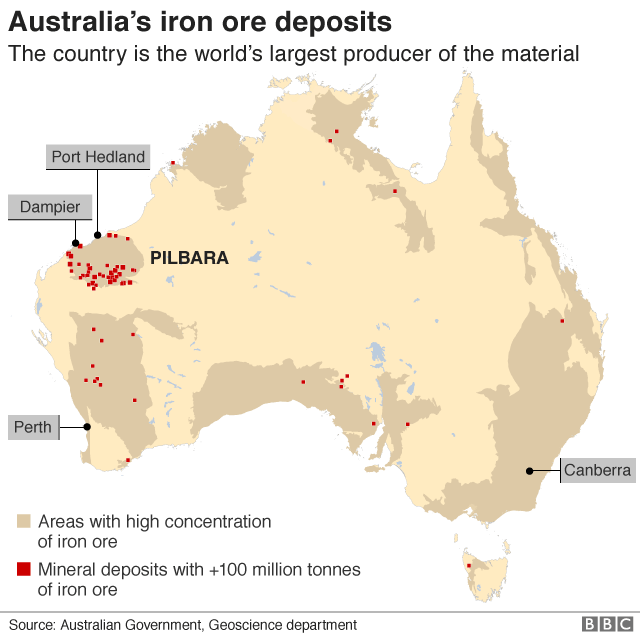

Australia is the world's largest producer of iron ore

It is the rock that has fortified Australia's recession-defying economy.

Iron ore has helped to raise living standards in the country, supercharge pension funds, and bankroll governments. It is the key ingredient of steel, and is Australia's most lucrative export.

Last year, the trade, mostly to China, as well as South Korea and Japan, was worth 63bn Australian dollars ($45bn; £35bn).

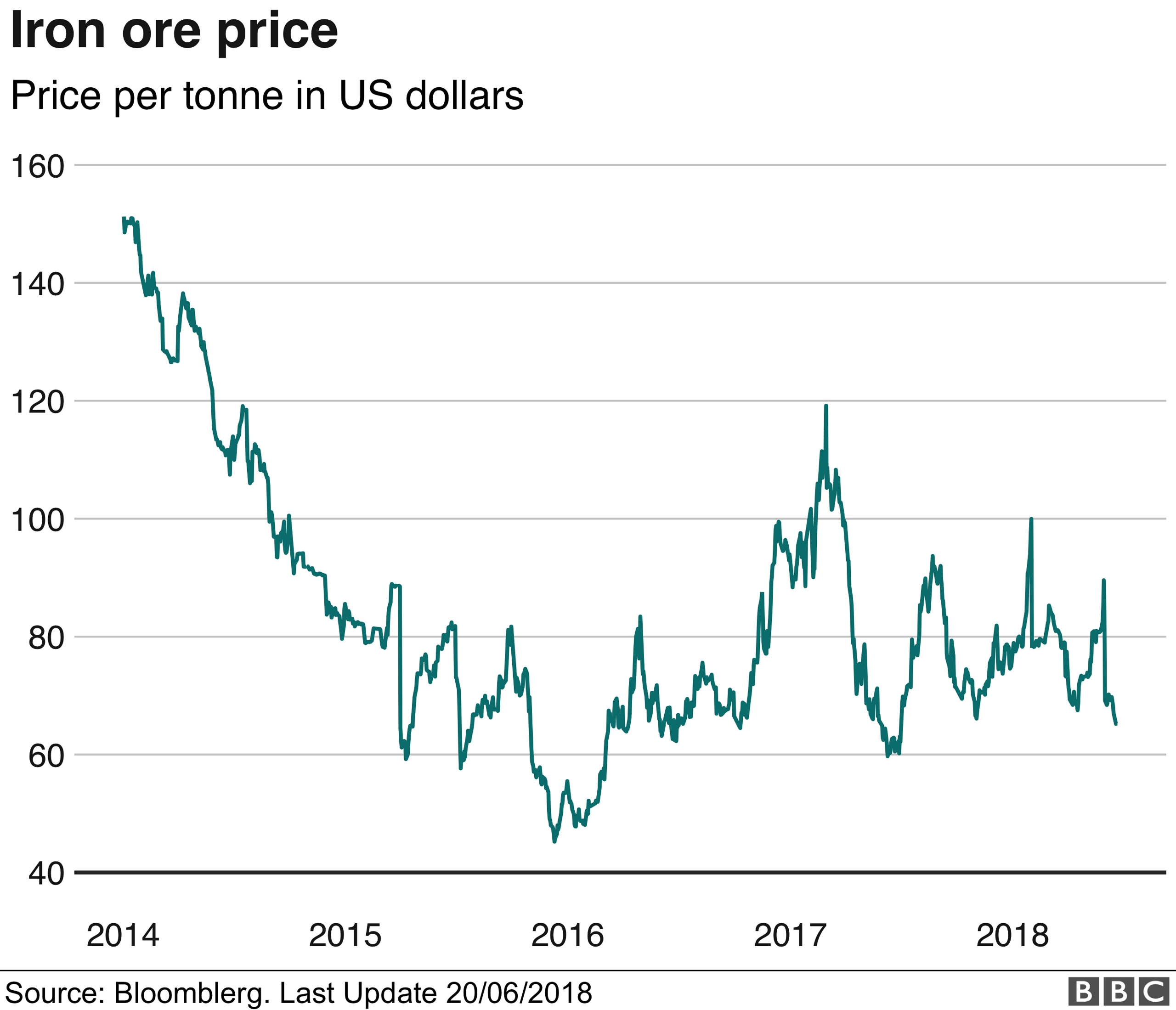

Over the past decade booming export volumes have soared by more than 200%. It is without doubt an economic colossus, and Australia is the world's largest exporter of iron ore. But given that global iron ore prices have fallen sharply over the past decade, should Australia try to move away from the sector?

The heart of iron ore extraction in Australia lies in the red, dry dirt of the Pilbara, a sparsely populated region in the north of Western Australia, more than 1,000km (621 miles) from Perth, the state capital.

The Australian iron ore industry is vast in numerous ways

"Our capacity to function as a government is directly connected to the success of the iron ore sector, so is the entire nation," says Bill Johnston, Western Australia's Minister for Mines and Petroleum.

"It is genuinely transformational. The iron ore expansion in Western Australia is simply breathtaking."

Iron ore mines are invariably far from the coast, and the resources companies have built railway lines to transport their rich quarry to Port Hedland, the world's largest bulk commodity terminal, and Dampier, another port to the west.

Excavators can shift up to 80 tonnes of earth in a single scoop, and trains taking the ore to the coast can be up to 2km long.

"The infrastructure required for this industry is on a scale that is almost impossible to understand without physically looking at it," says Mr Johnston.

"Just the export of iron ore through Port Hedland is 2.6% of Australia's GDP. This is just so fundamental to the success of Australia."

Iron ore is mined around the clock

The nation's earliest iron ore mine dates back to the 1870s in South Australia at the aptly-named town of Iron Knob in the Middleback Ranges, which is still in production.

But it was the legendary exploits of the so-called "flying prospector" that put the industry indelibly on the map. The story goes that in late 1952, mining entrepreneur Lang Hancock's plane encountered a heavy thunderstorm, and was forced to fly low under the clouds.

Navigating through a gorge in the Hamersley Ranges of the Pilbara, Hancock reportedly saw torrents of rain tumbling down its rusty red cliffs that were said to have resembled "walls of iron".

He bought the leases to the land and his iron ore legacy lives on. His daughter, Gina Rinehart, is Australia's richest woman, and remains executive chairman of Hancock Prospecting, the company her father founded.

The ore is transported to the coast by train

The rocks on which they have grown ultra-wealthy extracting are ancient, dating back to Precambrian times - specifically the Archean eon - and are about two-and-half billion years old. There are two basic types of iron ore - hematite (the more preferred) and magnetite, which can be processed into valuable metallic iron or steel.

"The big deposits are fortunate for Australia. They are a few hundred kilometres from the coast. It is pretty flat country," said Richard Blewett, the general manager of mineral systems at the government agency Geoscience Australia.

"Some of these ores are such high grade and such quality they are called direct shipping ores. You basically dig them out the ground, you put them on the ship and you truck them straight into a blast furnace and you make steel."

Thanks to Lang Hancock and others, Australia has been selling iron ore overseas for over half a century - first to Japan in the 1960s to support its post-war recovery, and in more recent times, to China.

Port Hedland is the world's largest bulk commodity terminal

China's voracious appetite for iron ore means that the country buys 80% of Australian exports of the raw material, which has helped Australia to avoid recession since the early 1990s.

"Each year the iron ore industry generates around $3.8bn in royalties for the state government of Western Australia," said David Byers, the interim chief executive of the Minerals Council of Australia.

"And major iron ore producing companies (BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue) pay around $2.25bn in company tax each to the federal government, again depending on commodity prices."

But while volumes of Australian iron ore exports have risen constantly since the start of the new millennium,, external the price of the raw material is now way below the highs of a decade ago. The global price of iron is currently around $64 a tonne, compared with a peak of $197 a tonne back in 2008.

This fall has led to some asking if the golden days of Australia's iron ore exports have come to an end.

Fariborz Moshirian, a professor of finance at the University of New South Wales Business School, thinks they have, and that Australia is looking elsewhere to safeguard its prosperity.

"I would say the resource boom is over," he says.

"To some extent the Australian economy is... adjusting to other sectors such as telecommunications, education, financial services and natural gas."

Global trade

More from the BBC's series taking an international perspective on trade:

He also points out that while iron ore production is a welcome earner for the Australian economy, "the size of the tax revenue is frankly not that significant when you look at the overall tax revenue".

Indeed, the Australian government gets most of its tax revenues from the services sector, which makes up 61% of the country's economy, and is growing strongly. By contrast, the mining sector - which includes iron ore extraction - accounts for 7%.

Most of Australia's iron ore exports go to steelworks in China

Meanwhile, a number of Australia's largest iron ore producers have announced in recent years that they are diversifying their businesses. Fortescue Metals is now looking at mining copper, gold and lithium, while Atlas Iron is also now targeting manganese.

However, mining officials believe the show is far from over, and point to more than 65 years of easily-mined iron ore reserves that are still to be exploited in Australia.

"2017 was the best year ever for the Western Australian iron ore sector," says Bill Johnston. "The best days of the iron ore sector are ahead of us."