In Nigeria this baby kit bag is saving mothers' lives

- Published

Peju Jaiyeoba has distributed half a million maternity kits across Nigeria

"Sometimes I just really hope that one day our work will no longer be needed." says Adepeju Jaiyeoba, the Nigerian founder of the Brown Button Foundation.

Seven years ago Adepeju, or Peju for short, ditched her well-paid job in law to train traditional birth attendants across Nigeria to deliver babies.

She then developed a cut-price bag of essential sterile medical kit that has sold across rural Nigeria saving thousands of lives.

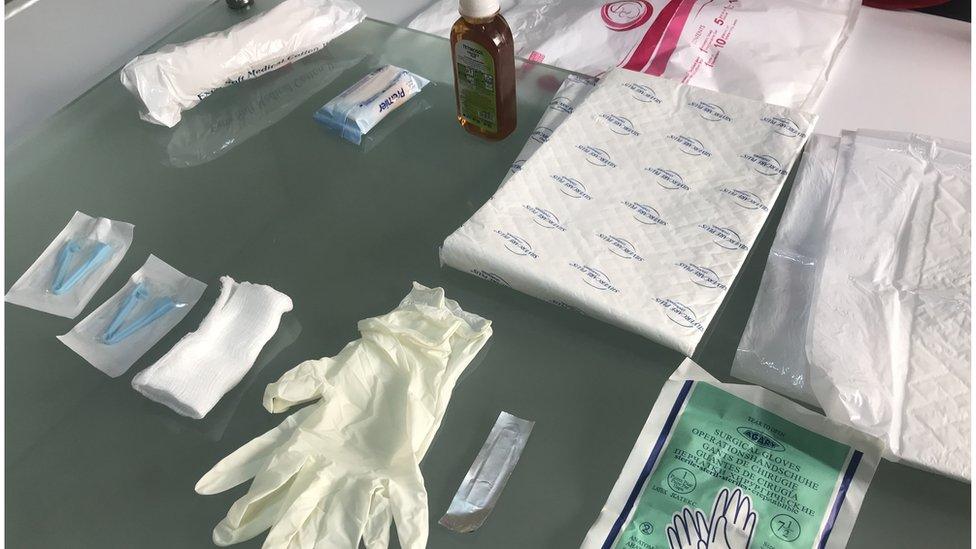

Costing around $4 (£3) the kit contains items such as disinfectant, sterile gloves, a scalpel to cut the umbilical cord, a mat to lie on during labour and tablets to reduce bleeding after birth.

Her friends and family tried to dissuade her from leaving her job but she says the death of a close friend in childbirth left her with no option.

"My friend was educated and it made me sit down and wonder that if someone who is financially solvent can die at childbirth, what is happening in rural areas where they do not have the facilities?

A baby is born on a mat from one of medical kitbags sold by the Brown Button Foundation

"I was really desperate I didn't want to lose anybody else. I do not think the process of bringing life should cause the death of another person," she says.

Along with her brother - a doctor himself - she decided, to find out for herself the reality of how women in rural areas of Nigeria were giving birth.

What she found was deeply disturbing.

"We saw women giving birth on bare floors, we saw nurses using their mouth to suck out the mucus of newborns to prevent asphyxia," she says.

"We saw birth attendants severing umbilical cords with rusty blades and glass, exposing newborns to neo-natal tetanus - and many of them dying.

"Basic things like washing your hands is a problem, and putting on a glove is a big deal."

Expectant mothers learn about the kits when they go for ante-natal checkups

Each day in Nigeria, 118 pregnancies end in death. The country has one of the highest numbers of maternal deaths in the world.

Giving birth is so risky, says Peju, that it has taken on a spiritual dimension - and women are far more likely to go a traditional birthing clinic where herbal remedies and prayer are more common than sterile equipment.

In response, she set up the Brown Button Foundation to train traditional birth attendants in modern methods of delivering babies.

Little did she realise at the time that while she was doing this, it would later provide a ready-made distribution network for her medical kit bags.

The contents of the kitbags are for one use only, so as to limit infections

"I realised that things we buy in Lagos are much more expensive in the north. A glove for example can be three times more expensive."

They did an initial run of 30 packs, negotiating with manufacturers for the cheapest possible prices - cheaper than the cost of the items in Lagos and far cheaper than the cost of the products in rural areas.

"Some people told us they would still not be able to afford the cost of the kit" she says.

"But they have a nine month period to contribute towards the kit. If at every antenatal they gave a contribution, then by the time they came to delivery it would be paid for."

Women can pay for the kit in instalments during their pregnancy

In the past four years, the Brown Button Foundation has distributed around half a million delivery kits.

The combination of training and delivering the packs has reduced deaths by bleeding after birth by a quarter in areas where they are used, says the foundation.

"The main thrust is in preventing infection in both the mother and the baby when it's born, and that's a good idea because infection is one of the causes of maternal mortality." says Bosede Afolabi, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Lagos University Teaching Hospital.

"If you have clean gloves, a clean area to deliver in and clean implements to cut the placenta and umbilical chord then you are likely to have a reduction in infection rates."

Peju's picture of her meeting with President Barack Obama has pride of place on her desk

One day Peju arrived at her office to a phone message from someone from President Barack Obama's White House.

She went home and told her husband about it and they agreed it was a probably a phone scam.

"Don't give anyone your pin number or your account number!" he told her.

But it really was an invitation from the White House. They were inviting an entrepreneur from each continent and Peju had been singled out as the person to go from Africa.

"I remember walking into the White House and it feeling like a dream" she says. "We talked about investment in Africa and health care. It marked a turning point for the work I was doing."

The BBC's Innovators series reveals innovative solutions to major challenges across South Asia and Africa

Learn more about BBC Innovators.

This BBC series was produced with funding from Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation