Social site terms tougher than Dickens

- Published

Children are baffled by Instagram and YouTube terms

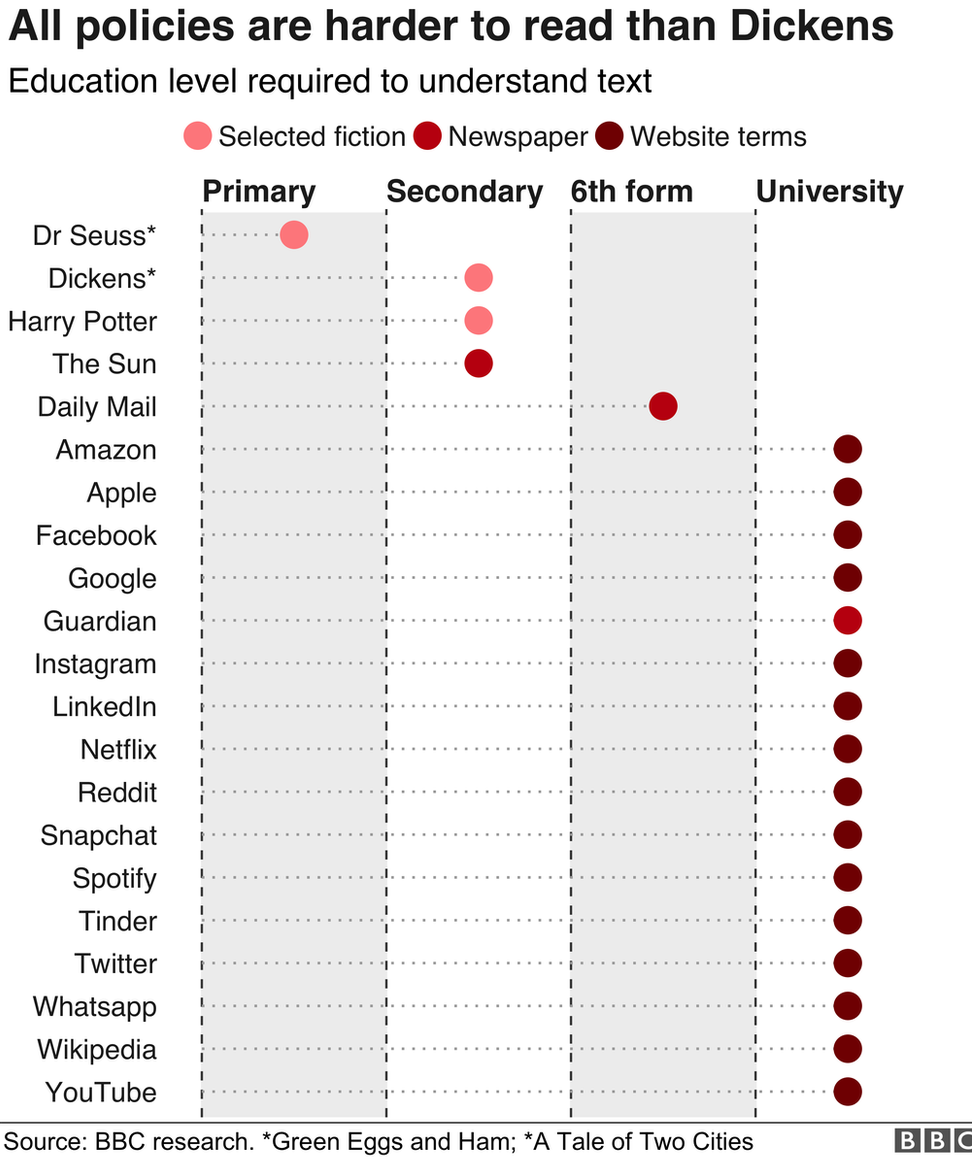

Children may be signing up to apps with terms and conditions that only university students can understand, BBC research reveals.

The minimum age to use apps such as YouTube and Facebook is 13.

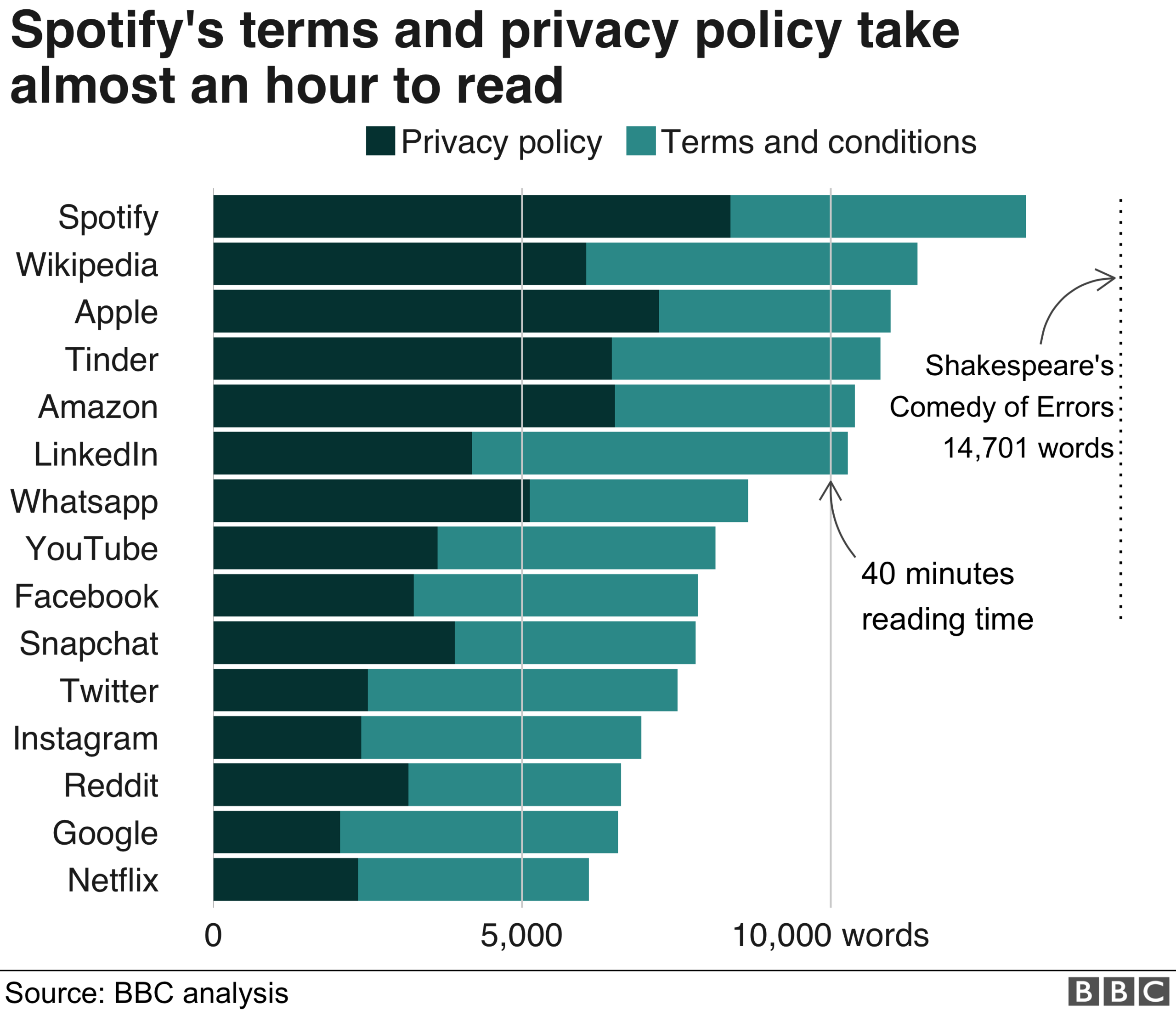

As well as using complex language, the BBC found that reading the terms of 15 popular sites would take almost nine hours in total.

Firms could be breaching European data rules, which require them to clearly spell out how they use personal data.

In response to the findings, MP Damien Collins accused tech companies of using terms and conditions to "exploit" users' data.

But several companies responded by saying they were working on improving the legibility of their legal documents by introducing easy-to-read summaries.

Facebook tracks you even if you don't have an account

LinkedIn scans your private messages

Tinder shares your data with other dating sites

How hard are they to read?

When using websites or apps such as Facebook, YouTube and Instagram, users must sign up to the company's terms and conditions, which include agreeing to be bound by a privacy policy.

According to Ofcom, more than eight in 10 children aged between five and 15 used YouTube last year.

The BBC carried out a readability test to work out the education level required to understand these policies. All 15 sites had policies that were written at a university reading level, and were more complicated than Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities.

This is despite the fact that YouTube, Twitter, Snapchat, Google, Instagram, Facebook, Reddit and Apple can all be used by children aged 13.

Mr Collins, who chairs the House of Commons Culture Committee, criticised the use of complex and lengthy terms.

"It's not enough to print a load of gobbledegook, that you know no one will ever read, and say: 'Aha, we've got the right to do it because it says so in here'," he said.

"You have got to make sure people are fully informed of what their rights are and why their data is being given away.

"We should make it a requirement of the tech companies to spell out in plain English what their users can do if they want to protect some of their data."

What does the law say?

The findings come as the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), which regulates how companies deal with personal data, says it plans to develop an Age Appropriate Design Code.

It says that this would mean those who design online services used by children, "know what we expect from them".

However, there may also be further consequences for companies who do not clearly explain how they use users' data.

The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force in May, says that companies must be clear about how they use personal data.

Article 12 says that communications to individuals about their data must be "concise, transparent, intelligible and [in an] easily accessible form, using clear and plain language, in particular for any information addressed specifically to a child".

Ailidh Callander, legal officer at Privacy International, a charity, says that companies have a legal responsibility to make policies concise and clear.

"The fact that privacy notices are still so hard to read raises concerns about whether these companies are complying with the law," she says.

How long are they?

As well as being hard to understand, some of the terms and policies take almost an hour to read.

Spotify had the longest combined policies at 13,000 words, just shy of Shakespeare's shortest play Comedy of Errors. Their terms would take an average person 53 minutes to read without breaks.

Netflix had the shortest combined documents, while Google had the shortest privacy policy - yet even this would take the average reader eight minutes to read.

To read all of the documents we looked at would take the average reader 533 minutes - or around nine hours, without breaks.

What do the companies say?

Several of the companies that responded to the BBC emphasised that they were constantly working on improving the legibility of their legal documents.

Google, Twitter, Facebook, Amazon and Wikipedia all pointed to their bespoke privacy centres or easy-to-read summaries, where users can find out more about how their data is used. Google, Twitter and Facebook said additional controls for limiting how user data is shared were easily accessible within their apps.

However Google maintained that the use of certain terminology in its legal documents was unavoidable, and Netflix said it was "legally bound to include certain wording and information".

Methodology

Our readability score takes an average of five different common readability measures. We analysed the policies as they stood on 15 June 2018.

For the news story comparison, we looked at two weeks' worth of front page stories from the Guardian, the Daily Mail and the Sun.

- Published6 July 2018

- Published3 July 2018

- Published2 July 2018