CO2 shortage: Why it really matters for the UK's food and drink supply

- Published

A shortage of CO2 gas is starting to bite. From pig processors to beer firms, the lack of carbon dioxide is hitting production. Booker, a wholesaler to bars and restaurants, is rationing sales. And soft drinks giant Coca-Cola says its UK bottling plant was interrupted by the shortage.

Trade journal Gas World, which first revealed there was a problem last week, said it was the "worst supply situation to hit the European carbon dioxide business in decades".

What is CO2 used for?

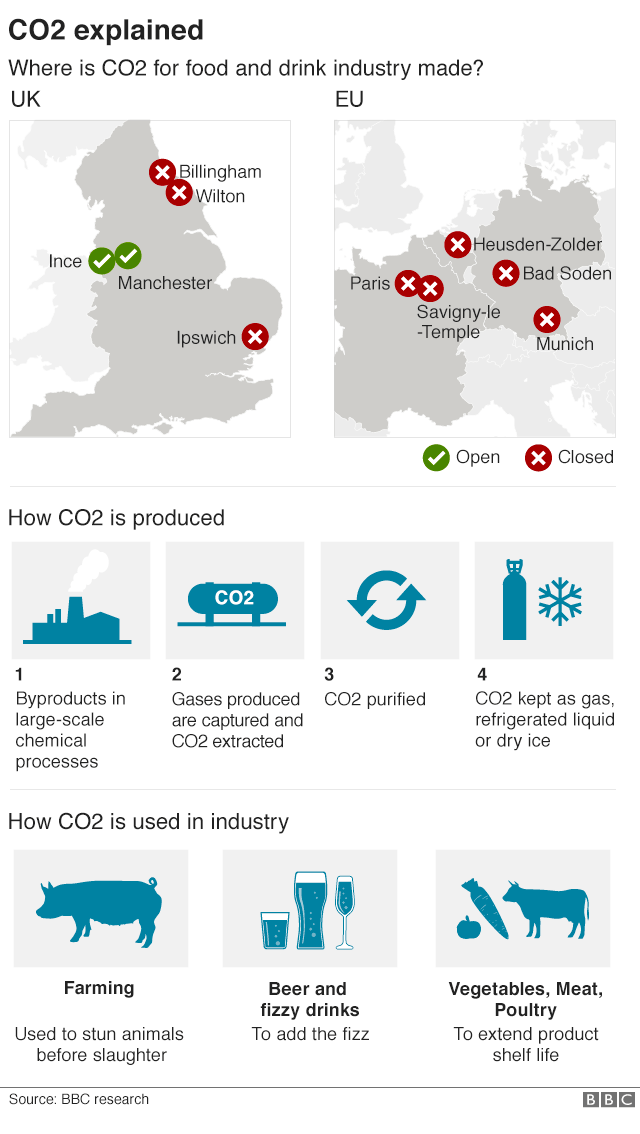

CO2 is widely used in the food processing and drinks industries. It puts the fizz into beer, cider and soft drinks, and is used in food packaging to extend the shelf life of salads, fresh meat and poultry.

The gas is also seen as the most humane way to stun pigs and chickens before slaughter.

Carbon dioxide is also needed to create dry ice, another product extensively used in the food industry to help keeps things chilled in transit.

The gas is also widely used outside the food and drinks sectors. CO2 is needed for certain medical procedures, and is used in the manufacture of semiconductor devices and by oil companies to improve the extraction of crude.

Why is there a shortage?

A lot of CO2 is, simply put, created as a by-product from ammonia production that is used in the fertiliser industry. Other sources are bio-ethanol plants.

However, a number of big mainland European fertiliser plants closed down for routine maintenance. And in the UK, only two of five plants that supply CO2 are operating at the moment.

Peak consumption for fertiliser is the winter, so chemical companies have traditionally scaled back production as summer approaches. Also, the current low price of ammonia means producers have little incentive to restart production quickly.

It's a case of bad timing that several plants wound down operations together, just as demand for food and drink was being ramped up by the good weather and football's World Cup.

Who has been affected?

The impact has been felt from the big drinks companies to the small bottling firms. Heineken said its John Smith's Extra Smooth and Amstel were hit, while Coca-Cola production was interrupted until fresh CO2 supplies arrived.

Tesco-owned Booker, a big supplier to restaurants and bars, has started rationing customers to ten cases of beer. And Ei Group, Britain's biggest pub operator, said some beer brands were in short supply or not available.

Scotland's biggest abattoir - which handles 6,000 pigs a week - has temporarily closed, with animals being sent to England for slaughter. But that is only a temporary solution, as these abattoirs, too, are also low on carbon dioxide.

Small UK bottling firms have also been hit. In the West Midlands, Holden's, which has 80 customers, shut down last Friday until further notice. "I'm left with people sitting around doing nothing," said operations director Mark Hammond.

Also in the West Midlands, a firm called The Beer and Gas Man, which provides CO2 to 750-plus pubs which use the gas to force drink through pipes and taps, has run out of supply.

Will we run out of beer and meat?

We seem to be a long way from this, although food and drink trade groups say much depends on how long the CO2 shortage continues.

The British Poultry Association say its members are "living day-to-day" in order to conserve dwindling CO2 supplies.

Morrisons supermarket has suspended online deliveries of some frozen foods due to a lack of dry ice (created from CO2). Ocado has done the same.

The Scottish Pigs Producers' co-operative is not ruling out meat shortages and higher prices, but does not want to be alarmist. And British Meat Processors Association chief executive, Nick Allen, said the situation was getting "pretty tight".

What is the government doing?

There seems to be very little activity at the moment.

The Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) says it "is aware that there are reports of a CO2 shortage", and is in contact with the industry and gas suppliers "to understand the implications of the situation".

That prompted one food trade body to tell the BBC: "They (Defra) will certainly have to wake up soon if this shortage continues for much longer".

However, there is very little the government can do to force CO2 suppliers to ramp up production. The situation is, said a government spokeswoman, "still industry-led".

Is there an end in sight?

There have been suggestions in the industry that supplies could start returning to normal in early July. Trade journal Gasworld reported that the shortage is likely to continue for the next week at least.

However, trade groups for both the food and the drinks sectors have criticised CO2 suppliers for a lack of communication, leaving them unable to plan for the future.

It's also likely that some companies will be given priority as supplies return to normal. Meat producers have asked for priority treatment, given that the welfare of animals is involved.

And smaller companies fear they will be put at the back of the queue as CO2 companies satisfy the demands of their biggest customers first.

- Published26 June 2018

- Published26 June 2018

- Published21 June 2018