Turkey accuses US of 'stab in back' as currency woes persist

- Published

Moves to ease Turkey's economic woes have failed to stop market turmoil as the country's row with the US deepens.

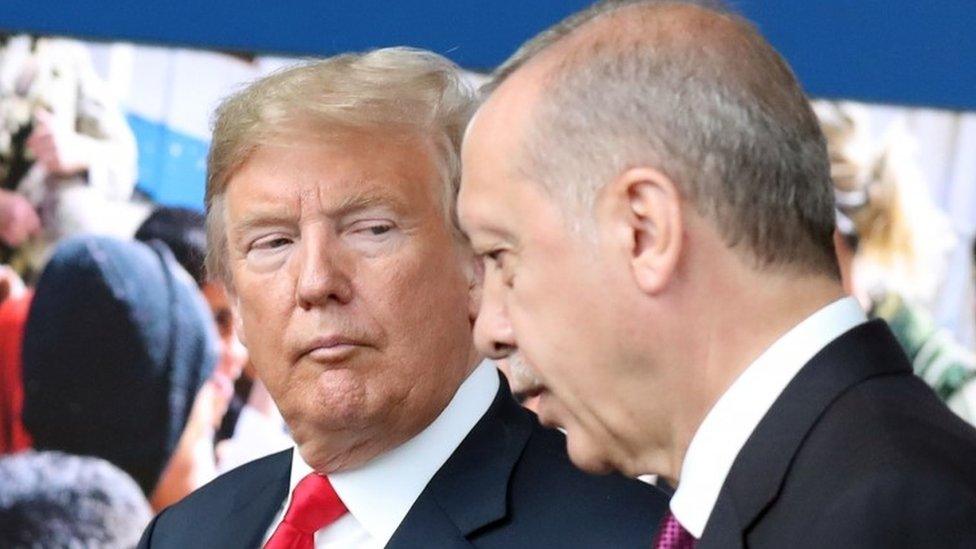

Turkey's President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, said on Monday that the US was seeking to "stab it in the back".

The US last week imposed sanctions on Turkey over its refusal to extradite a US preacher imprisoned in the country.

The sanctions caused market turmoil, which the central bank attempted - but failed - to soothe with a series of market-boosting measures.

Mr Erdogan told a news conference in the Turkish capital, Ankara: "You act on one side as a strategic partner, but on the other, you fire bullets into the foot of your strategic partner.

"We are together in Nato and then you seek to stab your strategic partner in the back."

The pastor is only one of a number of issues dividing Mr Trump and Mr Erdogan

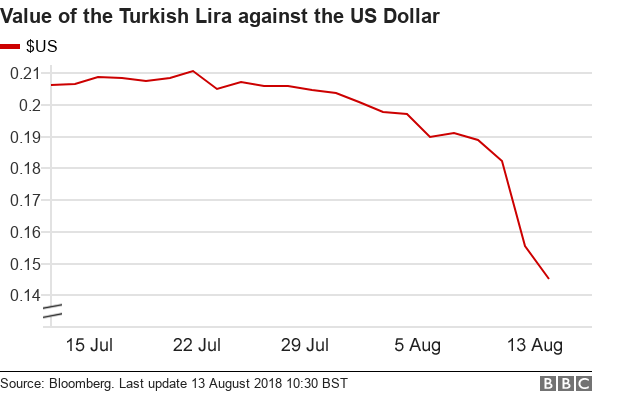

As the crisis deepened at the end of last week, the lira and the Turkish stock market slid sharply. Mr Erdogan, who has presided over soaring inflation and borrowing levels, says the lira's fall is the result of a plot rather than prevailing economic conditions.

Turkey's interior ministry said it was taking legal action against 346 social media accounts it claimed had posted comments about the weakening lira "in a provocative way".

Why are Turkey and the US at odds?

The dispute centres on Turkey's refusal to release American pastor Andrew Brunson.

Mr Brunson has been detained for nearly two years, accused of links to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers' Party and the Gulenist movement, which Turkey blames for a failed coup in 2016.

The Turkish president is angry that the US has not taken more action against the Gulenist movement and what he said was a failure "to unequivocally condemn" the 2016 coup attempt. The US has refused to extradite Fethullah Gulen, who lives in Pennsylvania.

Pastor Andrew Brunson was moved to house arrest last month due to health issues

US support for Kurdish rebel groups fighting Islamic State (IS) fighters in northern Syria is another major difficulty, given Turkey's battle against a Kurdish insurgency in its own country.

Mr Erdogan has also been getting closer to Russia. That creates an awkward triangle, given that Turkey is a Nato member, Russia is Nato's number one threat and the organisation is obliged to defend any member that is attacked.

Nato uses the Incirlik Air Base in Turkey to fight against IS and there has been some domestic pressure on Mr Erdogan to close it.

What is happening to the lira?

The lira's worst day was Friday, when US President Donald Trump approved the doubling of tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminium, following Turkey's refusal to free an American pastor who has been in detention there for nearly two years.

Experts have blamed the drop in the Turkish lira on fears that the country is descending into an economic crisis.

Turkey's stock market has also fallen 17%, while government borrowing costs have risen to 18% a year. Meanwhile, inflation has hit 15%.

Investors are worried that Turkish companies that borrowed heavily to profit from a construction boom may struggle to repay loans in dollars and euros, since the weakened lira means there is now more to pay back.

More than a third of Turkish banks' lending is in foreign currencies, according to Reuters, external.

Although the lira rose slightly after the central bank's move to support the economy, it still hit a new record low against the dollar.

Investors globally fear the damage spreading and have been prompted to sell riskier assets, including other emerging market currencies.

What are Turkish officials doing about the lira?

The Turkish Central Bank announced on Monday that banks would be given all the liquidity - help to keep money moving - they needed.

But the bank did not increase interest rates, which would help contain inflation while supporting the lira.

It is not clear if this comes after Mr Erdogan's pressure. The president is famously averse to interest rate rises.

He has dismissed the fall of the currency as "a storm in a tea cup" and urged Turks to sell dollars and buy lira to help boost the currency.

Analysis:

Andrew Walker, BBC economics correspondent

President Erdogan sees Turkey's problems as the result of a plot rather than economic fundamentals. That kind of talk might play well politically with some audiences in Turkey, but it won't wash in the markets.

Turkey has underlying problems in the form of a fairly large international trade deficit, high levels of foreign currency debt owed by the private sector and a persistent inflation problem.

Certainly the situation has been aggravated by the deterioration in political relations with the United States and the higher tariffs that Turkey now faces on its steel and aluminium sales in the US. But the scale of the apparent impact was due to the fact that Turkey was already economically and financially vulnerable.

What do people in Turkey think about this?

Business executive Kemal, who lives in Istanbul, said: "It is not unusual or unexpected to see some companies go under when there is such a sudden devaluation of the currency. However, I do not believe it will crumble the economy."

British holidaymaker Paul Fothergill, who is staying in Dalyan, says he has been holidaying in Turkey for the last 30 years. He said: "Since we arrived on Thursday the Turkish lira has nosedived. It's very sad for locals and investors, but incredibly good for us, the Brits.

"You can imaging how cheap our evening meals and trips have been. The most expensive meal, including drinks and tip, so far was £12 for me and my wife."

Heather, a Briton who has lived in Turkey for 15 years with her family, said: "This last year has seen ridiculous price rises and price differences in shops and supermarkets. Prices of basics like butter, cheese, fruit and vegetables are so expensive that we think twice about putting them in our baskets.

"Petrol and utilities have also seen price rises. Wages have not gone up, so we worry about where this will end. It may be beneficial for those with pounds, dollars or euros but rest of us are struggling."

- Published13 August 2018

- Published10 August 2018

- Published10 August 2018