How did Coca-Cola put fizz into its World Cup sales?

- Published

Coca-Cola was an official partner of the 2018 Fifa World Cup in Russia

Have you ever wondered why the products you see on supermarket shelves occupy the positions they do, and how retailers manage their stock levels? This is the science of shelf management and technology is playing an increasingly important part in it.

Following this year's Fifa World Cup in Russia, Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company (CCH), a major bottling partner for the global drinks brand, reported a 6.4% jump in revenues for the first half of 2018.

The football competition, warm weather and new product launches helped boost sales, the company said, but new technology also helped, in the form of sophisticated image recognition and data analytics.

CCH implemented a new system operated by tech firm Trax which digitised the previously manual stock-taking process.

When you have 200,000 retail customers across a geographically vast country like Russia, relying on pen and paper stock records that then had to be inputted into a computer was hardly ideal. It led to delays in replenishing empty shelves, which is not good for business.

Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company owns 10 bottling plants in Russia

Running out of stock costs retailers more than $634bn (£494bn) a year in lost sales, according to a report by retail analysts IHL Group.

And with the summer's World Cup attracting 4.5 million visitors, "it was highly important for us to get the right stocks in place," says Aleksandr Makarov, project manager for CCH Russia.

Implementing the Trax system resulted in a 63% reduction in "out-of-stock" occurrences and audit times that fell from 20 minutes to two minutes, says Mr Makarov.

"We achieved 99.5% product availability in stores three hours before the games started."

So how exactly did CCH achieve this?

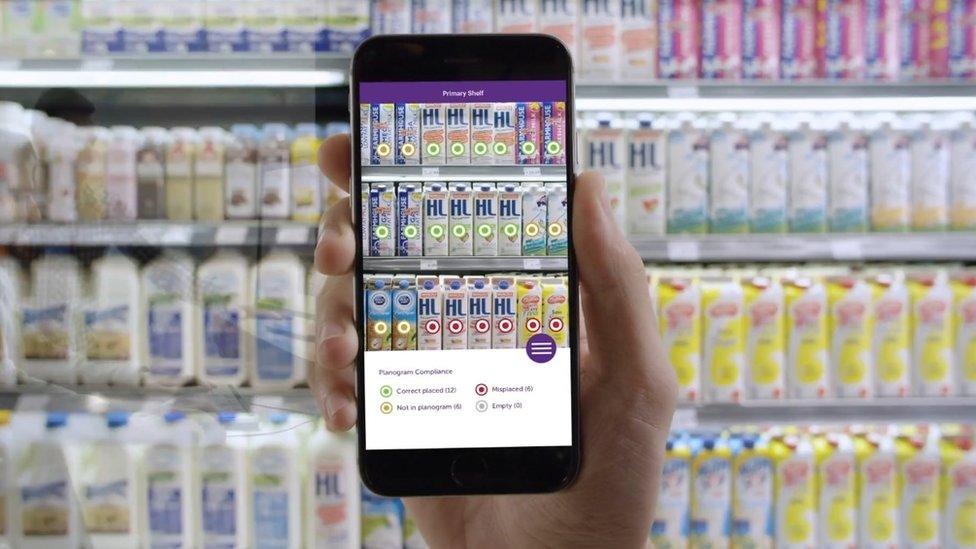

Trax uses on-shelf and smartphone cameras to analyse the position and availability of products

Using shelf-mounted cameras and augmented reality on smartphones and tablets, Trax's image recognition system monitors all the products on open shelves and in coolers, understanding how they differ in size, shape and colour.

A "panoramic stitching engine" pieces together the in-store images to recreate the full shelf, while analytic software recognises each product. The supermarket is instantly alerted if brands are out of place or missing from the shelves.

But, as Trax chief executive Joel Bar-El explains, "many products look the same but are in different sizes, like fizzy drinks, for example. So we've created an extra layer, understanding the physical layout of the store and looking at the price to help us work out the likely size of the product."

Shelf-mounted cameras monitor product position and stock levels in real time

The firm is identifying 250 million products a month and providing real-time data to 170 retailers and brand manufacturers around the world, says Mr Bar-El.

As bricks-and-mortar retailers face the growing challenge of online, a number of tech companies are springing up offering digital stock management and data analytics services to retailers - Planorama, TransVoyant and MetaMind to name but a few.

Shelf science

Supermarkets devise planograms - organisational charts - of where their tens of thousands of brands should go on shelves or in fridges and freezers. This helps store workers put things in the right place, because when it comes to grocery retailing, position matters.

Broadly speaking, premium products go on the top shelves, cheaper items on the bottom shelves, leaving the middle shelves for the best-selling mid-range products.

According to consumer organisation Which?, it's this "sandwich effect" that makes the profitable mid-shelf items seem more appealing. Clever packaging can subtly suggest that cheaper brands, placed near premium brands, are just as good.

Image recognition must differentiate between products that look similar but are different sizes

Brands pay handsomely for the right to occupy the best shelf positions, so they want to make sure retailers are doing what they promised to do. Sometimes they don't, whether through human error or poor planning. So real-time monitoring helps address this.

And they also want to make sure there's enough of their product in stock so there isn't a yawning gap on the shelf for very long.

"Retailers are out of stock about 8% to 12% of the time at the moment," says Mr Bar-El, "but systems like ours can reduce that to 3% or 4%.

"We alert them immediately. It normally takes three to four hours to replenish shelves today, but we've reduced that to 20 minutes in many cases," he claims.

Toby Pickard, head of insight for innovation and futures at retail analysts IGD, says using technology to ensure real-time stock management is becoming crucial for companies.

"As retailers increasingly match each other on price and range, excellent in-store service and product availability will become more important in terms of enabling retailers to stand out from the crowd and drive footfall to their stores," he says.

But, as Patrick O'Brien, UK retail research director at GlobalData, points out, "this is not exactly rocket science".

"Existing technology and shop floor staff should be able to maintain shelf stock, so it comes down to whether or not these providers can actually prove a return on investment," he says.

More Technology of Business

Data analytics is also revealing what's actually happening. And some of the findings are surprising.

For example, one pet food maker assumed that having its product positioned next to its main competitor wouldn't be good for sales. But it was. Why?

"We are not bothered by explaining why, we're just following the data," says Mr Bar-El. "It could be about colour, brain psychology, but we don't know. Our conclusions are evidence-based."

Online grocery shopping is growing quickly, with IGD forecasting 48% sales growth in the UK by 2022, 286% growth in China, and 129% growth in the US over the same period.

Won't this be a threat to in-store tech providers?

Chinese online retail giant Alibaba is integrating tech into supermarkets

"There is no question that online grocery will continue to grow and will undoubtedly become a main focus of both retailers and brands," says Mr Bar-El.

"But this increase in online sales is far from being the end of bricks-and-mortar stores. Online presents us with a far greater understanding of customer behaviour... the amount of data and insight that can be generated will help improve customer experiences, sales and overall understanding of every aspect of the business."

He envisages a hybrid world - a blend of online and physical, as evidenced by Amazon's bricks-and-mortar Amazon Go stores and Alibaba's "new retail" concept, which aims to combine the convenience of online ordering and home delivery with the fun of in-store shopping and eating.

"The future of retail is all about data, and the companies of the future are the ones who are learning to use it across all platforms - both digital and physical," he concludes.

So the next time you casually pluck that fizzy drink from the supermarket shelf, consider the science behind your decision.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external