Will we ever get self-healing smartphones?

- Published

The BBC's Circular Economy series highlights the ways we are designing systems to reduce the waste modern society generates, by reusing and repurposing products. This week we look at the prospects for hi-tech materials that can heal themselves.

You don't have to be a liquid metal cyborg assassin from Terminator 2 to know that the ability to self-heal can be pretty useful. After all, our bodies do it all the time, so what if our phones, prone to cracks and scratches, could do it too?

In January, tech giant Samsung filed a patent for an "anti-fingerprinting composition having a self-healing property", external and there's been speculation that such a coating might give its next smartphone the S10, which comes out in early 2019, the ability to self-heal small scratches too.

Although a patent is by no means any guarantee that a certain product will make it to market, this one has captured the attention of smartphone fans who have long yearned for more damage-resistant devices.

There has been speculation that Samsung's next smartphone may include self-healing technology

So how can an inanimate object possibly heal itself, and is it really likely that we will see self-healing phones, or other products, on the market any time soon?

Research in the world of materials science is often a lot slower and more sober than certain headlines would have you believe.

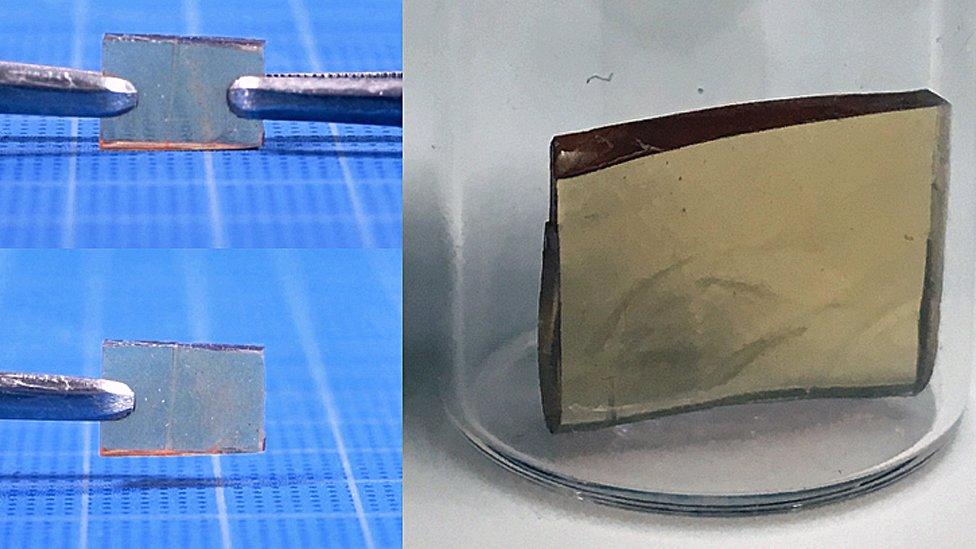

Take for example the self-healing polymer, a string of grouped molecules, reported in Science late last year, external. Discovered by accident, the polymer is able to self-heal when a small crack forms thanks to a substance called thiourea.

Takuzo Aida's team is working on these self-healing polymers

It contains hydrogen atoms that create new bonds with each other in a subtle zigzag pattern when the damaged material is squeezed gently. The zigzag repair line avoids crystallisation - which helps to keep the material rigid.

This was reported by lots of news sites as a potential smartphone screen material, but Tokyo University's Prof Takuzo Aida, one of the report's authors, tells me he doesn't think this particular polymer would be suitable. It's not necessarily strong enough to withstand the pressures of daily outdoor use, he explains.

"I think that the first application should be a device used [indoors]," he says.

Similarly, a self-healing polymer developed at the University of California, Riverside, external, has been touted as a potential phone screen saviour - but so far it has only been tested in artificial muscle models in the lab.

Self-healing polymers are likely to be first used in indoor devices, says Prof Aida

A self-healing screen is still possible but it may be a few years before you can buy one yet. Future phones may heal themselves in other ways, though. Internal circuitry could be resistant to damage thanks to self-healing conductive composites, external like the one being tested at Carnegie Mellon University.

"The idea of having electric circuitry that can repair itself without any human interaction or intervention does have potentially huge applications," says Rian Whitton at research firm ABI. But the people most likely to benefit from this technology may be those who need it for more specialised applications.

"Perhaps in high-risk situations involving first responders or military," suggests Mr Whitton.

To return to polymers, those in the know say that this class of self-healing material is reasonably well-developed, in fact some products do already contain them.

"You can already find some coatings, some car paints that include self-healing," says Sandra Lucas at Eindhoven University of Technology.

More car manufacturers will be using these self-healing coatings in the near-future

Indeed, US firm Feynlab has developed a coating for use on cars that contains ceramic polymers able to fill in small scratches, external.

"Imagine nano-sized magnets attached to the end of the durable ceramic chains, creating a memory-polymer," explains the company website. "The memory polymer recovers to its original (cured) state when heated."

How to heat your car? Leave it in direct sunlight - or pour hot water over the affected area. There are some eye-catching demonstrations of the coating instantly fixing itself, external online.

Surface scratches are one thing, but what if materials could heal deeper flaws too? Research into self-healing metals, a completely different material, is also yielding promising results at an early stage. The idea is to create metals that can better cope with the repeated pressures of daily use, known to cause structural failures.

"We know now that these cyclic stresses, although they do not cause shape change, they cause tiny cracks in the microstructure of the metal," explains Prof Cem Tasan at MIT.

Cem Tasan is investigating metals containing structures that can resist the growth of tiny cracks

More commonly known as metal fatigue, it is one of the suspected causes behind the catastrophic engine failure that hit a Southwest Airlines flight in the US in April, external. The US National Transportation Safety Board has said it found six crack lines on the fan blade that broke apart in mid-flight. It broke a window, almost sucking a woman out of the plane. The woman died of her injuries.

Circular Economy

More on the Circular Economy.

Prof Tasan and his team are investigating metals containing tiny structures that resist crack growth in each stress cycle. "It transforms to a new type of crystal but the new crystal is larger in volume," he says.

This wouldn't fill in gaps visible to the naked eye, but it could stop the proliferation of those micro-cracks behind metal fatigue, at the nano-scale.

Despite the many challenges involved in developing these technologies, the tantalising prospect remains: a future in which our phones, vehicles and buildings are safer all thanks to the power of self-healing.

- Published12 September 2018