How did the financial crisis affect your finances?

- Published

Ten years after the financial crisis, and the shockwaves are still being felt on people's finances.

Personal debt levels are at record highs and our banks are fast disappearing from the high street.

Low interest rate have left savers enduring a decade of paltry returns, but it's never been cheaper for mortgage borrowers.

In the changed financial environment, the question to ask is: "Are my finances fit for the next decade?"

Here, we examine four personal finances areas - homes, savings, borrowing and banking - to discover the lasting legacy of the financial crisis.

1. Homes

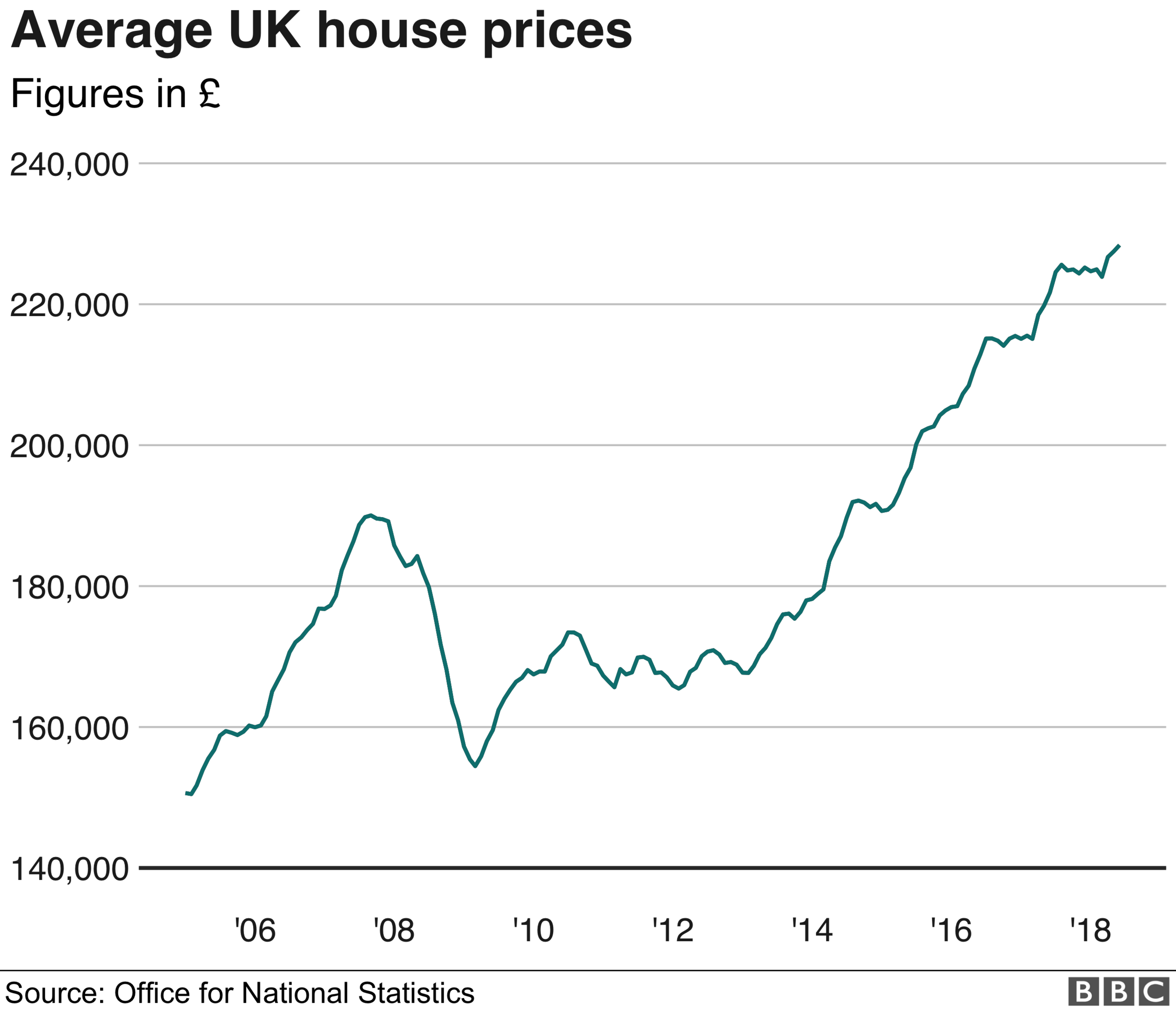

The average UK house price fell from a pre-crisis peak of £190,032 in September 2007 to a low of £154,452 in March 2009, according to data from the Office for National Statistics and the Land Registry. Since then, the price of an average house has recovered to £228,384.

Is that good news for homeowners? Not necessarily. There's no such thing as an average house, and for homeowners there's been a real north-south divide in the last decade in terms of property prices.

Londoners and those in the south-east have seen prices soar, but elsewhere in the country, the picture is much different.

Richard Donnell, insight director at Hometrack, said: "Although a decade has passed since the crash, house prices have still not recovered back to the levels seen in 2008 in many markets across Britain.

"Northern Ireland and parts of northern England, Scotland and Wales are the areas most affected. House prices continued to fall in the markets most affected for up to four years after 2008 as demand for housing was impacted by tighter credit availability and weak economic growth."

In the capital, house prices started to bounce back strongly in 2010 on rising employment and increasing numbers of overseas investors, he said. It means the whole of the London housing market has house prices that are more than 50% higher than 2008 levels.

What will happen next? Experts reckon prices will continue to rise but by less than in the last decade, and much less so in London.

The UK Office for Budget Responsibility has predicted property price growth will fall to 2.4% by the end of 2019, while estate agents Strutt & Parker have predicted a 2.5% rise a year over the next two years.

Meanwhile, accountants PWC have forecast that average UK house prices will rise by 4% a year until 2025.

2. Savings

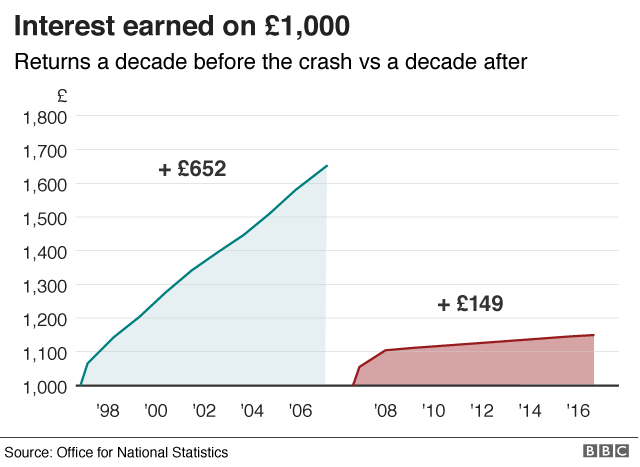

For Britain's savers, the last decade has been a disaster, especially those that had enjoyed decent returns in the years before.

In fact. £1,000 tucked away in a savings account a decade before the crash would have yielded a healthy £652 in interest. But anyone who stashed £1,000 in an account in the last ten years would have earned interest of just £149.

That's because in September 2008, the average deposit account paid interest of 3.1%, according to Bank of England data. That now stands at 0.43%.

Ten years ago you could get 5% on instant access savings, more than 6% on a one-year bond and 7% on a five-year bond from well-known established high street names.

Now the best rates are nowhere near as generous, with just 1.35% offered on instant access, 2.05% for one year and 2.70% for five years.

According to James Blower, founder of The Savings Guru, around 30 new banks and 40 new providers have entered the savings market since the crash. "The best interest rates almost entirely come from these new providers," he said.

Yet the traditional big financial institutions still hold around 85% of savings in the UK, with many savers' loyalty repaid by getting little or no interest on their nest-eggs.

Hargreaves Lansdown analysis suggests there has been a huge rise in the amount of money held in accounts paying no interest in the last decade, from £48bn in September 2008 to £164bn today.

"While the value of the savings market has continued to grow around 5% a year to more than £1.5tn, the new entrants have taken much of the growth in the market, rather than make significant progress against the big players," said Mr Blower.

But things could improve soon, predicted Sarah Coles, personal finance analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown.

"At this point, savers have reason to be marginally more optimistic about the future," she said. "That's because the regulator is looking more closely at how the industry functions, in an effort to protect savers from the lowest rates."

3. Borrowing

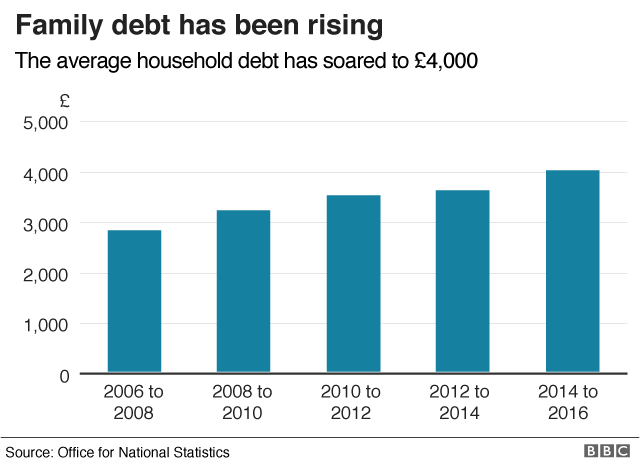

Average household debt has climbed from less than £3,000 to £4,000 in the last decade. There are lots of reasons for this, not least the easy credit that is available through plastic cards.

Credit card companies have been competing to offer ever-longer interest-free periods to attract customers.

In 2008 the longest 0% balance transfer was 15 months. Today, it is 36 months, although at one stage it reached a record high of 43 months.

Analyst Andrew Hagger, of Moneycomms,co.uk, said: "I'm not sure this is a good thing for all. Some savvy customers have moved balances around and paid little or no interest but others have struggled to repay their debt when their 0% deal ended - so are now being charged 20% APR or more."

He said it was one reason why personal debt levels have risen. "It's been easy and cheap money a-plenty over the last decade but paying it back will prove to be a long and costly struggle for some."

Overdrafts have also changed in the last decade. Most banks have changed the way they charge, moving from charging by a traditional interest rates to either daily or monthly fees.

"Providers have proclaimed that daily fees are easier to understand," said Mr Hagger. "That may be true, but at the same time they are also much more expensive for customers and a big profit driver."

The simple truth is that the way to reduce debt is to pay it off as quickly as you can and ignore the temptation of easy credit. With interest rates on the rise, what seems manageable debt now can quickly spiral into problems.

4. Banking

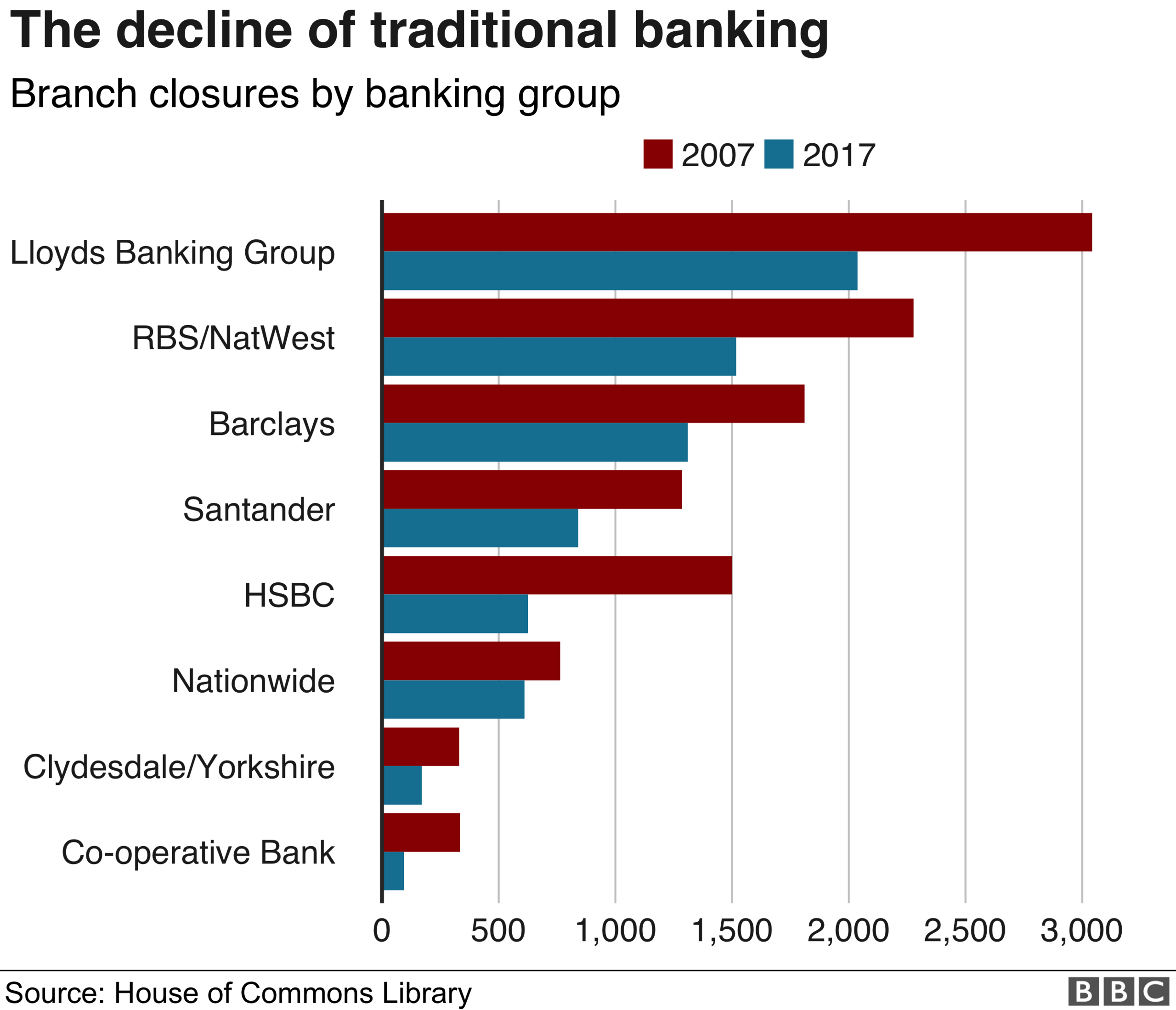

There's a completely different banking landscape from 10 years ago, not least because traditional players have been busy closing branches.

But at the same time the crisis marked the beginning of the entry of a whole new range of challenger banks.

Back in 2008, the most likely challengers looked set to be the supermarkets, Tesco and Sainsbury's. Now the biggest challenge to traditional banking comes from branch-free app banks, such as Starling or Monzo.

Julian Skan, senior managing director in banking at Accenture Strategy, said: "Wider competition is now coming from platform players, which didn't exist ten years ago, and who have greater opportunities to bite at banking revenues."

But he warned that computer attacks are likely to increase in the years ahead, bringing a fresh challenge. "Resiliency in the face of growing cyber risks is the new threat," Mr Skan said.

But there also needs a change in outlook, according to Bevis Watts, managing director of ethical challenger Triodos Bank UK.

He said: "The pace of change has been far too slow and more needs to be done to re-purpose banking for good, through greater transparency on how money is used, carbon disclosure, impact reporting and using risk capital weightings to account for environmental and societal risks."

In other words, banks need to respond to the changing demands from customers in the next decade.

- Published12 September 2018

- Published12 September 2018

- Published12 September 2018