Has 'dieting' become a dirty word?

- Published

Fay Marshall says losing weight has changed her life

Fay Marshall used to weigh 21st 5lbs (136kg). In two years she lost 8st 8lbs (54kg) and since then her entire life has changed.

The 24-year-old has moved from London to Lancashire for work, regularly goes out with friends and has even done a sky dive.

"I've completely overhauled my life. There were so many barriers through being overweight."

She had tried "every diet going" to lose weight since the age of 13, including counting calories, drinking shakes instead of meals and Weight Watchers. In the end, she says it was joining Slimming World that worked.

The weekly sessions involved being weighed privately followed by group meetings that included healthy cooking lessons and discussions about the difficulties of losing weight.

She joined after twice being offered seats on the Tube by people who had assumed she was pregnant.

Unsurprisingly, Fay explicitly joined Slimming World because she wanted to lose weight.

Britain is ranked as the sixth fattest nation in the world, according to research firm Mintel, and like Fay many people want to be slimmer.

Yet wanting to lose weight is increasingly seen as old fashioned, and anti-feminist even in the #MeToo era.

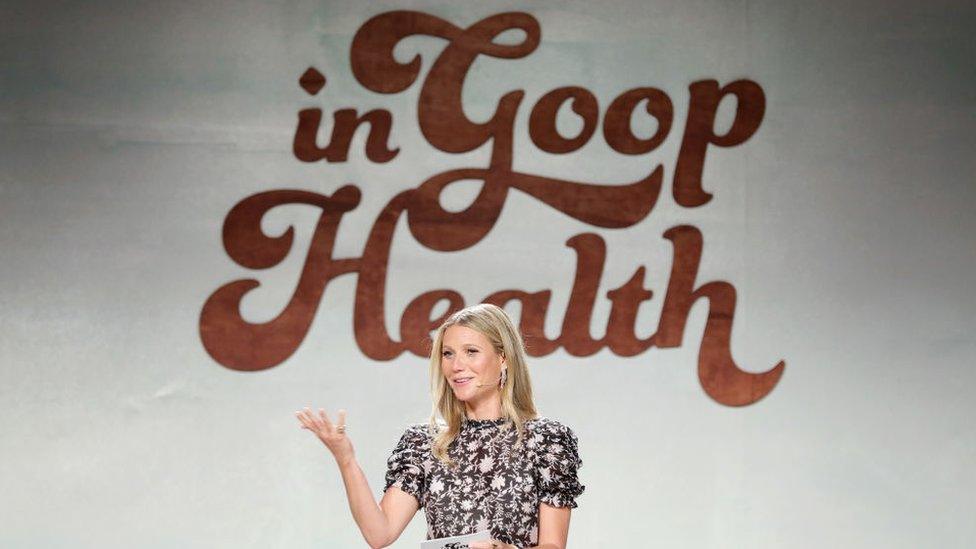

Goop has been criticised by doctors and scientists who allege that it uses pseudo-science to peddle products

Just this week Weight Watchers announced it was ditching the word "weight" from its name to rebrand as WW. Chief executive and president Mindy Grossman said the change reflected the company's broader focus on "wellness".

A day later, Oscar-winning actress Gwyneth Paltrow brought her wellness brand Goop to the UK, opening her first shop in Notting Hill, west London.

"Wellness" is the new industry buzzword, a handy catch-all encompassing good mental and physical health and the promise of something more than just a smaller dress size.

A diet that boosts energy levels is now almost as attractive to people as one that results in a healthy weight, according to a recent survey by Mintel.

Shedding pounds, bikini bodies and fat shaming are out, while body positivism and social media hashtags such as #StrongNotSkinny and #FitNotThin are in.

"If I saw a body like mine on this magazine when I was a young girl, it would have changed my life," Tess Holliday said of her Cosmo cover

Cosmopolitan magazine's decision to chose American model Tess Holliday, who is a UK size 26, as the cover star for its recent issue illustrates this growing acceptance that women come in all shapes and sizes. But the move was also condemned by many for encouraging obesity.

This is the dilemma. While words such as "dieting" and "losing weight" may seem outdated, many people do still want to be thinner and being overweight can have negative health implications.

So is embracing body positivism and wellness really the right approach?

Awkward conversations

Dr Matthew Capehorn, a GP based in Rotherham who also works as a medical director for commercial weight loss firm Lighter Life, says the danger of talking about wellness without focusing on weight is people may overindulge on healthy food and continue to gain pounds.

"At the end of the day, if someone is overweight they need to lose weight."

He points out the NHS's National Child Measurement Programme, which weighs and measures schoolchildren, uses "very overweight" to categorise clinically obese children. He says this can lead to awkward conversations with parents who don't realise the seriousness of the issue.

He says medically a patient's overall health is the priority. "We don't want to see lower numbers on the scale for the sake of it. If [overweight] people lose weight then they inevitably become healthier," he says.

But he warns that most commercial weight loss firms lack the expertise to make much difference to people's health other than weight.

In contrast, he says specialist weight management services from the NHS can encompass the physical, metabolic and emotional perspective of weight loss because they have the professional knowledge, equipment and medicine to do so.

At Slimming World, exercise is called "body magic"

Nonetheless, Helen Barrett, a specialist mental health dietician for the NHS, says changing how we talk about weight loss can be effective.

She says the word "diet" has become "a very negative term" despite it simply meaning the food that we eat.

With her patients she focuses on what they want to achieve by losing weight, rather than the weight loss itself.

Wanting enough energy to play with their grandchildren, is an example she gives. "Weight is connected in there, but it's not the primary driver," she says.

This is important because it also takes into account people's mental wellbeing, often overlooked in weight loss, she says.

"Losing weight won't make someone happy. You will probably still feel sad inside, potentially even more so because it raises questions over your identity," she says.

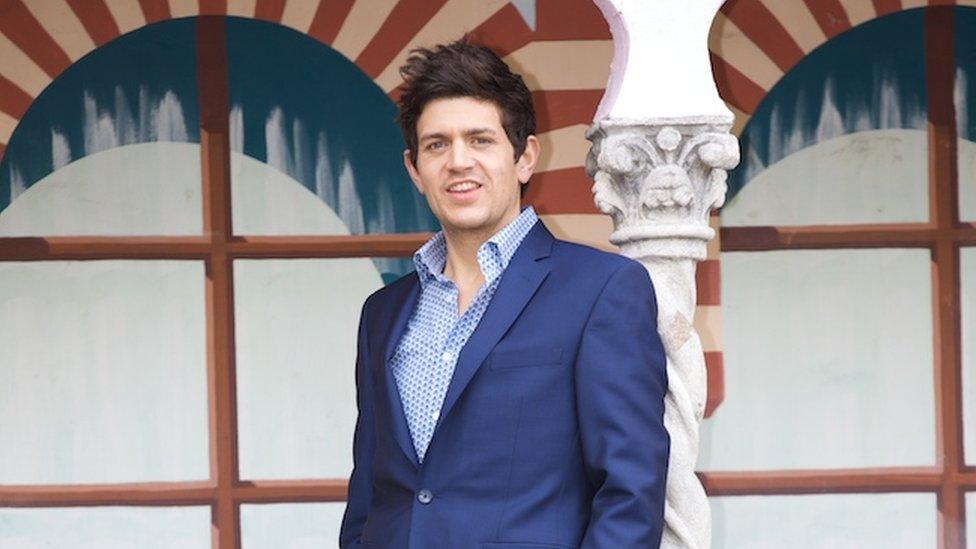

Matt Briggs lost 17-and-a-half stone in just over two years

It sounds counter-intuitive. Fay says for her losing weight was always the goal. Before Slimming World, she felt stuck in an unhappy cycle, eating junk food, getting bigger, not wanting to go out because she was bigger and then comfort eating to cheer herself up.

She credits losing weight with giving her the confidence to do things she felt she couldn't do before.

"If I was starting again I would still focus on the weight aspect," she says.

'Elephant in the room'

Matt Briggs, a consultant for Slimming World who leads group sessions, agrees. He lost 17-and-a-half stone in just over two years through the programme and says for him too weight was the starting point.

"To not discuss it is the elephant in the room," he says.

Yet for many people overeating is not just about food - there's often a psychological reason behind the extra pounds. If this aspect of being overweight isn't addressed then the danger is that people simply return to their old habits over time.

Matt links his own weight issues to his mother having multiple sclerosis (MS) and comfort eating to help him deal with it.

The weekly group sessions, he acknowledges, touch on these types of issues.

For example, one of his group members has reached her target weight, but hasn't accepted it yet and doesn't feel happy. With her, he says, they avoid talking directly about her weight, instead focusing on what she's done that week.

"You have to be able to unpack something. If we just focus literally on weight you probably wouldn't get through the levels of it all," he says.

'Body magic'

Slimming World also uses some language tricks to try to make dieting less daunting.

Exercise is called "body magic", for example, to avoid intimidating members who are new to physical activity. And while the firm doesn't use calorie-counting in their weight loss plans, calorific foods are labelled as "syns" and limited.

Of course changing your language to embrace the latest dieting lingo is a savvy marketing move. It opens up a broader range of potential customers enticed by the prospect of more than just a lower number on the scales.

But unless it is accompanied by a genuine attempt to help deal with people's psychological complexities and embrace a healthier lifestyle in the long term, then really it's just dieting in disguise.

- Published24 September 2018

- Published25 September 2018