Sky battles: Fighting back against rogue drones

- Published

A New Orleans police officer shoulders a drone capture "gun"

Rogue drones have nearly caused air accidents, have been used as offensive weapons, to deliver drugs to prisoners, and to spy on people. So how can we fight back?

This summer a packed Airbus A321 came within 100ft (30m) of disaster after encountering a drone at 15,500ft.

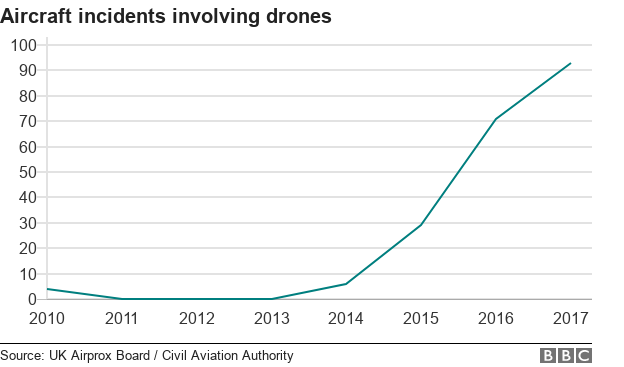

And the number of near-misses of this sort has trebled over the last three years, with 92 incidents reported last year in the UK alone. Dozens were classified as involving a serious chance of a collision.

"We are seeing an increase in reported incidents," says a spokesman for the UK's Civil Aviation Authority (CAA).

"A lot tend to be away from the airport, but some are very close, and we see them particularly around London."

Drones are also being used by so-called Islamic State in Syria and Iraq as offensive weapons. On one occasion, a small number of drones carrying hand grenades were able to take out an entire Russian weapons depot.

And criminals and their associates have been using them to smuggle drugs and phones into prisons in the UK.

So what can be done to prevent drones from flying places they shouldn't?

Several companies, including Droptec, OpenWorks Engineering, and DroneDefence have developed hand-held or shoulder-mounted "guns" that fire a net to trap a suspect drone.

The weighted net entangles the drone and brings it to the ground

They've already been used to protect heads of state on foreign visits and other dignitaries at international meetings.

For example, Droptec's kit was used to protect US President Donald Trump on an official visit to Switzerland earlier this year - although the authorities won't say whether it saw any action.

OpenWorks has also developed an automatic mounted gun that can identify, track and capture drones that fly within a prohibited area.

OpenWorks Engineering's anti-drone gun can be operated remotely...

...and automatically tracks a suspect drone before capturing it in a parachute-equipped net

Other security firms have installed net capture tech into interceptor drones that can lock onto a rogue drone and disable it in mid-air. This type of system was deployed at the Winter Olympics in South Korea in February, and has been used by police in Tokyo for the last three years.

But such net capture guns are more useful if used in conjunction with other detection technologies.

Earlier this summer, Southend Airport trialled a drone detection system called Skyperion developed by the UK's Metis Aerospace, which uses a combination of radio frequency detection and optical sensors to spot unauthorised drones.

"The trial was useful," says Damon Knight, the airport's head of air traffic services. "The manufacturer discovered a lot about the environment they would have to work in, searching for a wi-fi signal in an area that's very hot in terms of wi-fi use."

In other words, identifying a specific wf-fi signal coming from a drone and its controller in an area packed full of other wi-fi signals being accessed by phones and broadband routers is no easy task.

Metis Aerospace boss Tony Burnell says: "We're looking at the protection of privacy and illegal and nuisance drones around football stadia, sports events, music venues and so on."

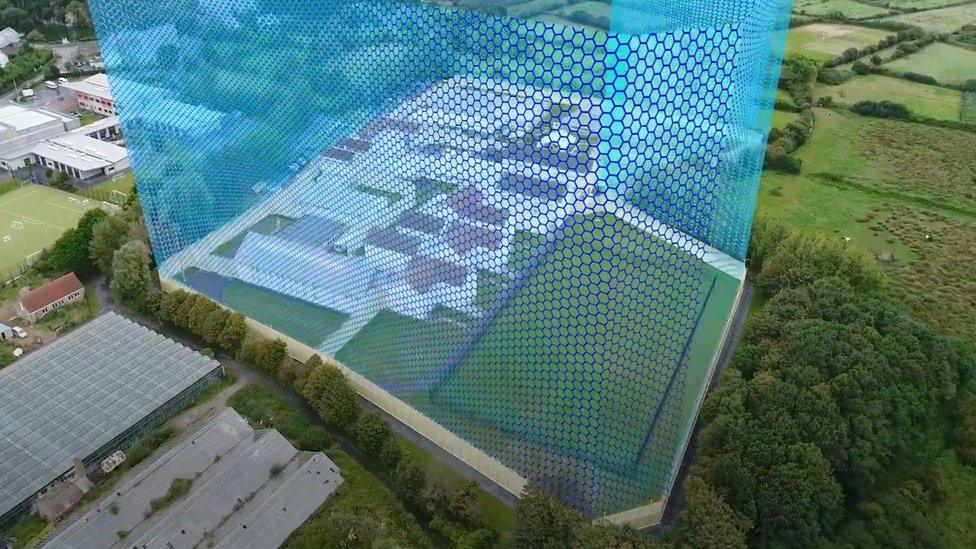

Once a drone is detected, SkyFence uses signal jamming to disable the intruder

Last year, Les Nicolles Prison in Guernsey installed a system called SkyFence developed by tech firms Drone Defence and Eclipse Digital Solutions.

A series of sensors around the perimeter of the prison identify any incoming drones. Once alerted to an intruder, the system fires up multiple radio transmitters that emit a signal designed to overwhelm the drone's radio transmissions.

This interrupts the connection with the operator and stops the drone proceeding any further.

And as most drones are programmed to return to their last point of control if the signal is lost, it gives law enforcement a chance to track the drone and trace the operator.

But one problem with all these drone detection and neutralisation systems is that they require a high level of technical competence on the part of the operator. Outside the military, this isn't always easy to achieve.

The SkyFence creates a protective wall of radio jamming signals around the perimeter

"Drone detection is a requirement of many agencies that can't afford to have trained experts with knowledge of these systems," says Mr Burnell.

"They want automatic detection... and to do that needs a lot more automation and understanding to get a high level of detection and a low level of false alarms."

The answer, he says, is to train the anti-drone system using artificial intelligence (AI).

"The AI is machine learning, training the computer to learn rather like a human does," he says.

Tempting as it might be, civilian organisations aren't allowed simply to shoot down nuisance drones - in the UK at least. That's left to the military.

"There's a lot of legal issues - notwithstanding the danger of a drone crashing to the ground and potentially injuring somebody," says Mr Knight.

For its part, the industry is doing what it can.

For example, most major drone manufacturers incorporate geo-fencing - the ability to recognise no-fly zones and avoid them using a combination of GPS and Local Radio Frequency Identifier (LRFID) connections, such as wi-fi or Bluetooth.

Meanwhile, larger drone users are required to register in the US, the UK and some other countries. But neither of these measures is terribly hard to bypass.

Instead, governments around the world are considering whether to allow anti-drone systems to be installed more widely, not only at prisons and airports, but also at large public events.

Come in rogue drone, your time is up.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external