IMF World Bank: What the economic outlook holds for Asia

- Published

Clouds on the horizon. Dark undercurrents in the global economy. Trade tensions. Vulnerabilities in the global financial system.

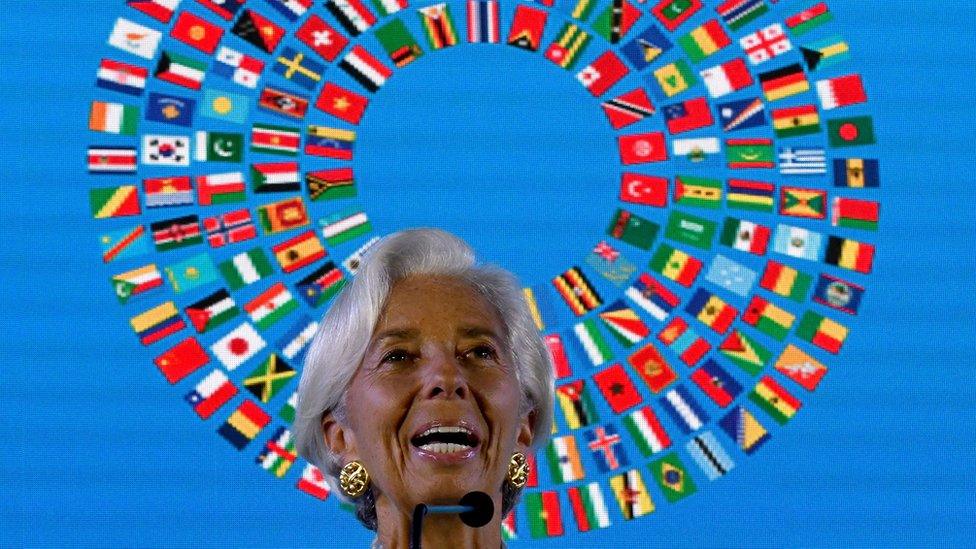

You wouldn't be blamed for thinking the annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank in Bali last week were full of doom and gloom.

So how worried should we be about Asia's economies?

Here are some of the key risks I'm watching:

Emerging market contagion

Turkey and Argentina were highlighted as key risks, according to the IMF. There have been worries those troubles would infect Asian economies too, in particular countries like Indonesia and India which have seen their currencies fall to near record lows recently.

But one of the key themes I heard repeated consistently by fund officials was that while there are vulnerabilities in emerging markets, the IMF doesn't see risk of a spillover just yet.

There are countries that are more vulnerable than others as David Lipton, first deputy managing director of the IMF, told me. But for now the IMF is monitoring the situation rather than switching into panic mode.

The comparison for some countries, including host Indonesia, is that the weakness in their currencies could lead to a massive outflow of funds the way we saw during the Asian Financial Crisis. At the time, sharp recessions occurred and many countries had to turn to the IMF for help - including Indonesia.

But as this data from the Institute of International Finance shows, external, Asian emerging markets are much stronger now than back then.

Systemic risk is lower than in 1997, but as the data shows there is one possible currency risk. That comes in the form of being exposed to any devaluation in the Chinese yuan as a result of trade tensions between the US and China.

China is the biggest trading partner for most Asian countries including Indonesia. This means that if the Chinese currency gets weaker, that puts pressure on Asian currencies and makes their goods more expensive versus Chinese goods - leading to more pain.

China worse off in trade war

Both China and the US saw their growth outlook trimmed because of the trade war, but China was likely to be worse off, according to data from the IMF.

China is expected to grow by 6.6% this year, but next year sees a reduction to 6.2% - shaving 0.2% from the IMF's original forecast.

The fund also said in a report that if not for Beijing's recent actions to try and boost growth in the face of the trade war, the outlook for the mainland could be even worse.

One of the ways that some analysts have anticipated China could mitigate the risks of the trade war is by devaluing its currency.

But in a statement released on Saturday, external, the fund members agreed to "refrain from competitive devaluations" and not to target exchange rates for "competitive purposes".

According to media reports, China has agreed to this in principle - but the Chinese currency has lost close to 10% of its value this year, and many analysts are pointing to more depreciation ahead.

Key to watch will be how much the Chinese allow their currency to fall, and whether the US Treasury calls Beijing a currency manipulator in a report due this week, external - which would ratchet up tensions even further between the two superpowers.

Pakistan bailout

During the meetings, Pakistan formally asked the IMF for financial assistance, a process which will now include negotiations and talks to determine the size and scope of the help they will need.

The Pakistani economy has reached emergency-status and some reports say that it will need close to $15bn (£11.4bn) from the IMF as a bailout. But this money won't come for free.

The IMF will insist on financial reforms, and it is also being reported that Pakistan may have to reveal the amount of debt it is taking from the Chinese government for the Belt and Road programme.

Beijing started the $62bn programme in Pakistan three years ago to build roads, power plants, a port and other infrastructure.

But recently there's been a growing backlash against taking on Chinese debt to fund infrastructure, in what the US has been calling Beijing's "debt diplomacy."

Whether Pakistan will shelve or have to trim back on China's Belt and Road initiative will be watched closely as a sign of the pushing back on Chinese influence in the region.

- Published7 September 2018

- Published5 July 2018

- Published9 September 2018

- Published10 August 2018

- Published21 August 2018