Budget 2018: Why is it so hard to spend money on roads and rail?

- Published

It's not easy getting big infrastructure projects finished, or even started.

There have been discussions for decades on what to do about the volume of traffic on the A303 going past Stonehenge in Wiltshire.

Proposals for a tunnel under the World Heritage Site were made in the mid-90s, with plans for a tunnel approved by the government in 2002, external.

After years of protests, a public inquiry and spiralling costs, the plans were scrapped by the then transport secretary in 2007, external.

In the Autumn Statement in 2013, the then chancellor George Osborne resurrected the plans with a feasibility study, and there was an announcement in 2017 that there would indeed be a tunnel.

It's possible that work on the tunnel will begin in 2021, external. Thirty years is not a lot compared with the 5,000 or so years that the stones have been there, but it illustrates how difficult it is to carry out this sort of work.

Crossrail was first proposed in a Greater London Council rail report in 1974

Paul Johnson, head of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), told a committee of MPs, external last year: "I was in the Treasury in the early 2000s when investment spending was rising. Literally, the underspends were multiple billions every year, because it could not get out of the door, and quite a lot of what got out of the door was not terribly well spent."

Sir John Armitt, chairman of the National Infrastructure Commission, told The House magazine, external last week that the key to speeding up large infrastructure projects in the UK was to reform the way that compensation is paid to those affected by them.

Everyone thinks infrastructure spending is a good idea. At the 2017 election, the Conservative manifesto, external included infrastructure in the first of its "five giant challenges" and mentioned infrastructure 26 times, while Labour pledged, external to spend an extra £250bn over 10 years on infrastructure.

But successive governments have not been very good at putting the amount into capital investments that they say they are going to. Reality Check approached the Treasury to ask why, but did not get a response.

The bit of government spending that includes infrastructure is called Public Sector Net Investment (PSNI). It includes infrastructure projects such as roads and train lines, research and development, IT equipment and property.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, which assesses the government's Budget plans, is currently forecasting that over the next five years the government will invest £17.5bn less in capital projects than it has said it will (see table 2.19 of this spreadsheet), external.

A report by the IFS, external found that between 2010 and 2016, PSNI had been on average 8% lower than the government had said it would be. This compares with an average of 13% between 1998 and 2010.

Unusually though, in 2008-10, the Labour government actually managed to spend more than it had said it would. That was because investment had been brought forward from the following year as the government tried to deal with the impact of the financial crisis.

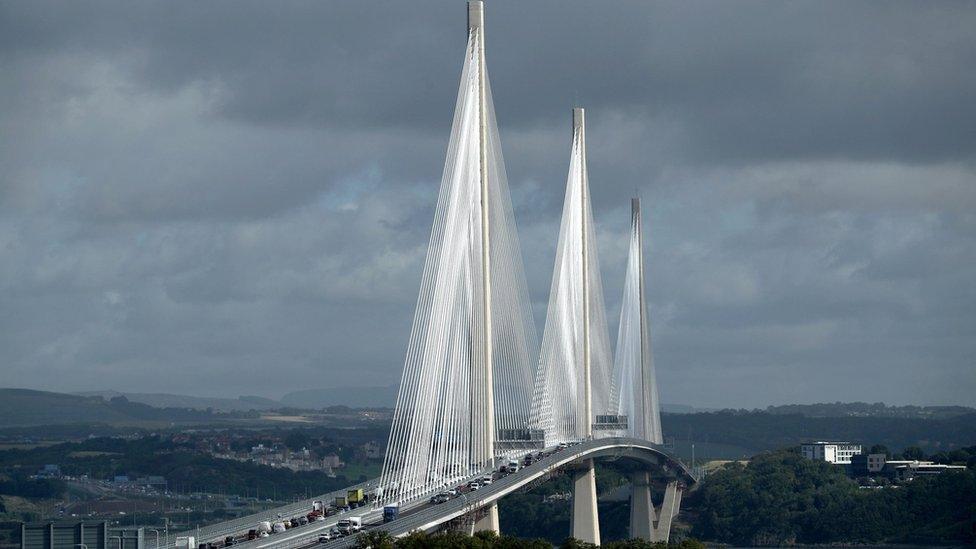

The Queensferry Crossing opened last year - the idea of a second Forth Road bridge was proposed by the Scottish Office in 1992

There are several reasons why governments generally spend less than they planned to on capital investments.

The first is the obvious one - getting projects off the ground means having teams in place to implement them, getting planning permission and all sorts of possible delays such as archaeological objections, as happened with the A303.

Another thing to remember is that PSNI is a net figure - it's the amount spent on capital investment minus any assets that have been sold off. So, for example, if the government sold off some its land or property it would reduce PSNI for that year.

In recent years, there have been some examples of public services taking money that they were supposed to be spending on investment and using it for day-to-day spending instead.

This year, for example, the Department of Health and Social Care switched £1bn, external from the money it was supposed to spend on capital investment and used it for day-to-day expenses "to meet spending pressures".

Local authorities have also been allowed, external to make "flexible" use of funds earmarked for capital spending.

Finally, there are sometimes changes in what counts as public sector investment spending. For example, since the reclassification of housing associations as part of the private sector (except in Northern Ireland), money spent on affordable housing would no longer count as part of PSNI.

23 October update: This article previously stated the selling of government shares would reduce PSNI. This has been amended to reflect that a reduction in PSNI would only apply to the selling of physical assets (eg land and property).