Brexit: Can firms stop stocks running low?

- Published

Stockpiling is moving up the agenda as Brexit approaches. Concerns about shortages of food, medicines, car parts and much else as the UK adjusts to life outside the EU are growing. Premier Foods, the company behind Bisto and Mr Kipling, is the latest firm to say it will build stocks of raw materials. It sounds simple. But in an era of cross-border supply chains, it isn't.

What's the issue?

Unless you've been living on Planet Zog, you'll have noticed that Britain plans to exit the European Union - at 11pm UK time on Friday, 29 March 2019, to be precise. What's spooking many business leaders is that the UK risks leaving without a deal on future trading relations. The smooth transition of goods into - and out of - the UK will be severely disrupted, they say. Frictionless trade is essential to keeping supermarket shelves well stocked and factories ticking over. "Nothing but scare-mongering," shout the critics. "Just Project Fear". There is, though, no question that the number of companies making contingency plans is rising.

Who's stockpiling - or thinking about it?

Just about everyone who imports into the UK from the EU will be giving it some thought. Premier Foods says it's simply making contingency plans for a range of Brexit scenarios, adding that it has had a team in place for months keeping things under review. But now Premier has moved from the review stage to taking active steps. The company estimates stockpiling could cost it up to £10m.

Mondelez, the owner of Cadbury, is stockpiling ingredients, chocolates and biscuits. Meanwhile, Airbus, which makes aircraft wings in the UK, has asked suppliers to build up inventories. Carmakers are doing similar things. Jaguar Land Rover has warned of huge costs, disruption and job losses if there is no deal.

In the UK government's regular worst-case planning updates to business, pharmaceutical firms were advised to keep six week's worth of drugs in stock. AstraZeneca is increasing its drugs stockpiles in Europe by about 20% in preparation for a no-deal.

So food supplies will be OK?

Not necessarily. For many business leaders the impact on the food chain is the most worrying part of leaving the EU without a deal. It's one thing stockpiling metal components, but perishables are entirely different. Just over 40% of UK food is imported, with about 30% coming from the EU.

Mike Coupe, chief executive of Sainsbury's, says the sector can keep about one week's worth of food in cold storage. "It's straightforward - perishables can't be stockpiled," he told the BBC. If delivery lorries face increased customs checks and start backing up at ports the whole system breaks down. The food sector, just like the manufacturing sector, operates to just-in-time schedules.

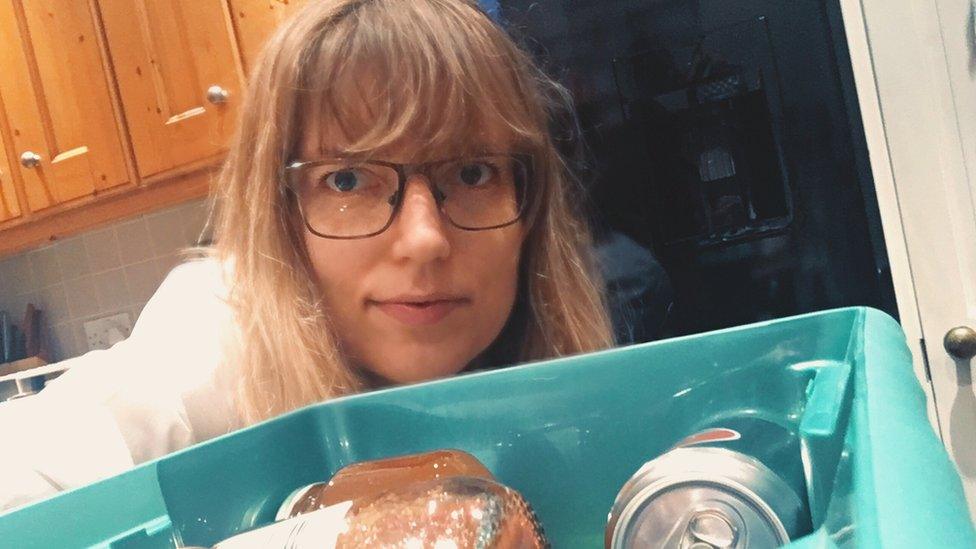

That said, Mr Coupe thinks a Brexit deal will be done and that the industry will cope. But it hasn't stopped anecdotal evidence that individuals have begun stockpiling their favourite foods. There's even a Facebook group called the 48% Preppers - named after the proportion of people who voted to remain in the 2016 referendum - that advises consumers on stockpiling.

It doesn't sound like there is real cause for alarm

Publicly, the supermarkets are cautiously optimistic. But Tim Lang, professor of food policy at London's City University, says "supermarket bosses are a bit more concerned than they are letting on".

He told the BBC: "We tend to focus on the supermarkets because most food is bought via the supermarkets. But there is a vast structure to the food industry. It's a hugely complicated system." Never mind the big players, it's the small food packaging firms or sandwich makers that could really suffer.

There are not enough warehouses in the UK, Prof Lang says. "There are some people I talk to who are already at the limits of what they can do. There's no storage left, there's no chilled storage, no frozen storage," he says. "Are we right to be worried? Yes. Panic? No."

Can't we just build more facilities?

One company trying to address the issue is Wild Water, which stores imported raw ingredients and finished food. It has rented extra space, and is building a large facility at Aberbargoed, in Wales. Customers were "ultra-concerned" about food being held up at ports, says managing director Ken Rattenbury. "We're turning businesses away every day, every single day."

Companies are freezing ingredients, he says. "They're worried about the raw ingredients to be able to make ready meals, they're concerned about flour, they're concerned about juices. Everything you can think of that we use for food. Everybody is looking to stockpile."

That's OK for frozen produce, but consumers often want fresh. Besides, there's a fear that the UK has left it too late to build the necessary facilities, not just for food but for stockpiling generally.

Peter Ward, chief executive of the UK Warehousing Association, wrote recently that he'd been "warning for two years [that] fit-for-purpose, appropriately located warehousing is in desperately short supply in the UK".

If we rely solely on UK production we wouldn't be able to eat strawberries year round

Can stockpiling be all bad?

That depends on whether you have the warehousing space, a supply chain able to cope with new demands, customers willing to adapt, and money to invest in buying additional stock up-front. And to repeat, a lot of food can't be stored for longer than a couple of days.

However, the CEBR economics think-tank says there could be a short- term economic boost. It estimates that of the £260bn worth of goods imported from the EU last year, about £100bn were raw materials and semi-manufactured goods. If companies want to build up, say, a three or four month buffer, that would imply up to £40bn in unplanned extra purchasing and boost the GDP figures.

Financing this stockpiling may be manageable for a big multi-nationals, but perhaps not for small widget makers operating on wafer-thin margins. And there will be a hangover, the CEBR says, as companies begin to run down inventories in the following months.

What does the government say?

It was only a few months ago that Dominic Raab, the Brexit secretary, insisted that he would ensure the UK had adequate food supplies, suggesting that it could be stockpiled. Critics ridiculed the idea, saying he misunderstood the food chain.

But the Department for Exiting the European Union is adamant that people shouldn't be concerned, saying that the government is preparing for all eventualities but had no plans to stockpile food and people should not do so either.

A spokesman told the BBC: "The UK has a strong level of food security built upon a diverse range of sources including strong domestic production and imports from third countries. This will continue to be the case whether we leave the EU with or without a deal."

- Published13 November 2018

- Published24 August 2018

- Published9 November 2018

- Published9 November 2018