Thomas Cook: What went wrong at the holiday firm?

- Published

- comments

It's been a long journey for travel firm Thomas Cook since its formation in rural Leicestershire during the early Victorian era.

Founded in Market Harborough in 1841 by businessman Thomas Cook, the fledgling company organised railway outings for members of the local temperance movement.

Some 178 years later, it had grown to a huge global travel group, with annual sales of £9bn, 19 million customers a year and 22,000 staff operating in 16 countries.

Thomas Cook had a chequered history, including being nationalised in 1948 - when it became part of the state-owned British Railways - and owning the raucous Club 18-30 youth brand, which it recently closed after failing to find a buyer.

However, just as the travel world had progressed from temperance day trips, so the modern business and leisure market was also changing, and at a far faster pace than in previous decades.

The firm's fate was sealed by a number of factors: financial, social and even meteorological.

As well as weather issues, and stiff competition from online travel agents and low-cost airlines, there were other disruptive factors, including political unrest around the world.

In addition, many holidaymakers had become used to putting together their own holidays and not using travel agents.

"The company has had troubled for a long time," said John Strickland, an aviation analyst who provided evidence to a government inquiry into the 2017 collapse of low-cost airline Monarch, external.

As for Thomas Cook's recent attempts to restructure itself, "it looked to me very much like too little too late," he said, adding that a move into the package holiday market by low-cost carriers EasyJet and Jet2 piled on the pressure.

Tim Jeans, a former managing director of Monarch who left long before its collapse, told BBC 5 live Thomas Cook had "an analogue business model in a digital world".

Now chairman of Newquay Airport, in Cornwall, Mr Jeans was an executive at MyTravel, which owned AirTours and was bought by Thomas Cook in 2008, an investment that was recently written off.

Much of the value of the business was perceived to be in its brand and the loyalty of its customers, accounted for in its books as goodwill.

The firm had very little in the way of tangible assets, such as planes or hotels. So, when customers left for online competitors or to book their own flights and hotels, the value of the firm plummeted, said Mr Jeans.

Thomas Cook's airline had 94 planes

Last summer, shares in Thomas Cook were trading at just below 150p. But after a series of profit warnings, the price had fallen to just a fraction of that. Earlier this year, analysts at Citigroup bank described the travel firm's shares as "worthless".

In May, Thomas Cook reported a £1.5bn loss for the first half of its financial year, with £1.1bn of the loss caused by the decision to write down the value of My Travel, the business it merged with in 2007.

However, it warned of "further headwinds" for the rest of the year and said there was "now little doubt" that Brexit had caused customers to delay their summer holiday plans.

The company then put its airline up for sale in an attempt to raise badly-needed funds.

Thomas Cook later announced it was in advanced talks with its banks and largest shareholder, China's Fosun.

The troubled operator hoped to seal a rescue led by Fosun, but the creditor banks issued a last-minute demand that the travel company find an extra £200m, which it was unable to do.

2018's summer heatwave in the UK was blamed for falling bookings

The company's boss, Peter Fankhauser, said the firm had "worked exhaustively" to salvage the rescue package and it was "deeply distressing" that it could not be saved.

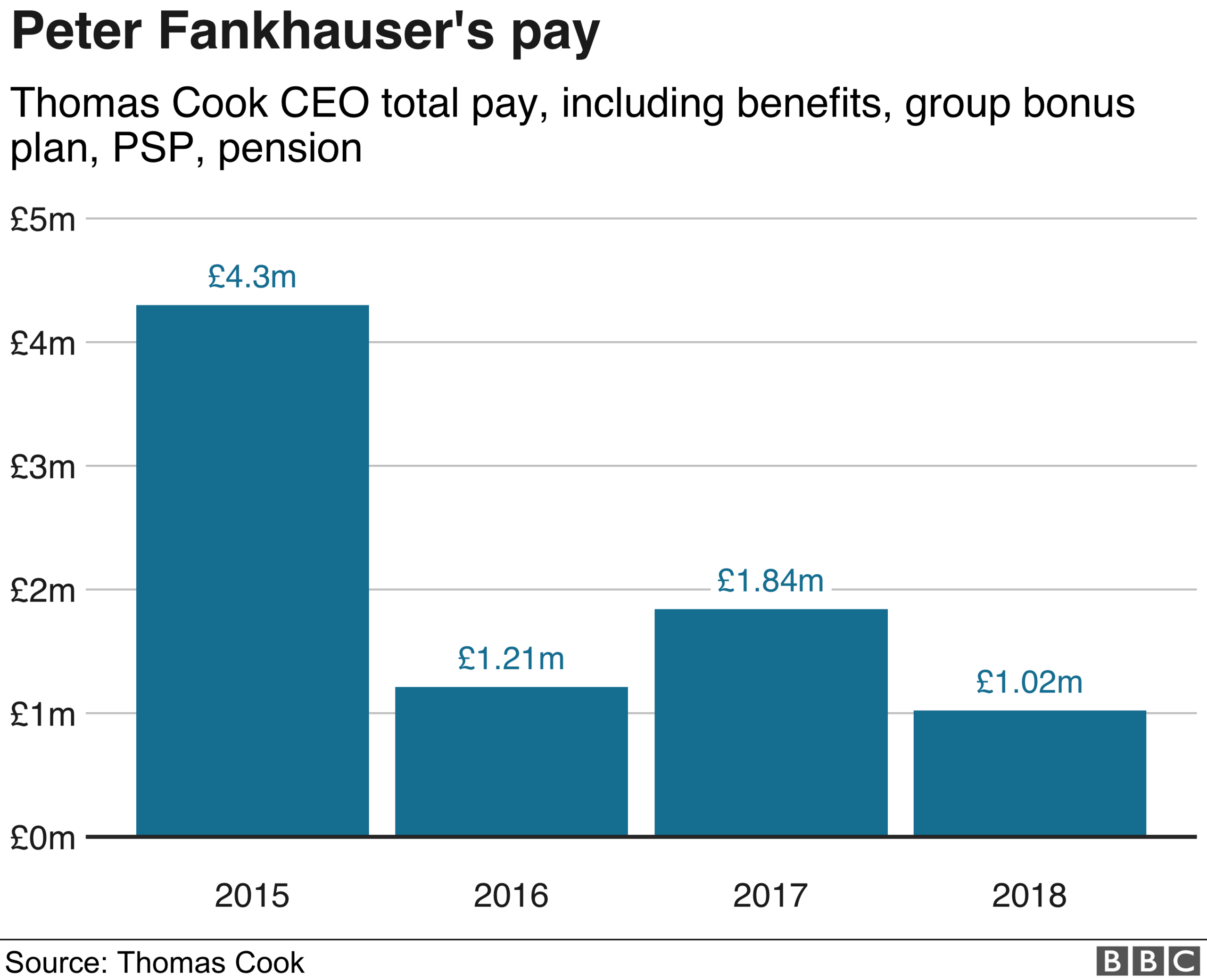

He and other executives received millions of pounds in bonuses, salary and other perks to retain their talents.

Investors, lenders and staff may be wondering precisely how wisely this largesse was calculated.

For Thomas Cook's unfortunate staff, customers and shareholders, history has come full circle.

Eight years ago, the company lurched perilously close to the edge of insolvency after trading turned sour. It was pulled back from the brink by an emergency loan from a group of banks, led by Royal Bank of Scotland - ironically the same bank whose demand for extra money appears to have sunk the company this time.

As well as weak trading, the company's big problem in 2011 was too much debt - about £2bn when the pension deficit was included. It tried to put its borrowing problem behind it in 2013, with a £425m fundraising from shareholders.

Fast forward six years and Thomas Cook is back where it was. All the rescue money is gone and the debt pile is back to £1.6bn. Again it has been thumped by poor trading and a series of one-offs, notably weak sterling and a summer heatwave that led to a downturn in demand.

But there is evidence of deeper problems, as well as a lack of management control. The company stopped paying dividends to shareholders in 2011 as the previous crisis hit, but resumed them in 2017 and again last year - an odd thing to do if trading, and solvency, was tight.

The company's results were marked by exceptional, one-off items, always a red flag for analysts, while the negotiations over the restructuring plan have been chaotic.

After the immediate repatriation and staff problems have been resolved, one question remains: will Thomas Cook live on in some form?

The obvious buyer would be Fosun, the Chinese conglomerate that was the British company's largest shareholder. But they, and other buyers, may conclude the messy nature of the weekend's collapse may have blighted the brand irretrievably.

The package holiday share of the market has remained broadly unchanged.

One reason for this is that most air package holidays sold by travel companies based in the UK have ATOL protection, external.

This protection means that if the business collapses while travellers are away on holiday, they will be able to finish their trip and then travel home.

If a business folds before someone's trip, the scheme will provide a refund or replacement holiday.

Mr Strickland, the analyst, said a tax was suggested by his panel to fund repatriation of customers of failed travel companies, reducing the risks to the taxpayer.

However, airlines argued that more successful airlines should not be punished for the failure of competitors, he said.

Mr Jeans, the former Monarch executive, said aircraft flights will have been managed to bring them back to the UK and avoid them being seized by creditors.

"It's very important they get back to their home base, in this case the UK, so that things can be sorted out more simply."

- Published21 September 2019

- Published28 August 2019

- Published12 July 2019