What can New Zealand teach us about Brexit?

- Published

New Zealand's economy was forced to diversify after the UK joined the European Economic Community

Brexit is, to put it mildly, an unusual event.

But there are precedents for some aspects of it.

New Zealand provides one example. The country faced a sudden, adverse change in access to a key export market when the UK joined the European Economic Community (EEC), as it was then, in 1973.

When countries have changed their trade arrangements through negotiation in recent decades it has usually been to reduce barriers to cross-border commerce.

We don't know exactly what Brexit will bring, but it certainly could - or perhaps we should say probably will - mean more barriers to trade between the UK and EU.

And it could all happen very quickly, especially if the UK does leave the EU without a Withdrawal Agreement in March next year.

There aren't many precedents for that.

What happened to New Zealand in 1973?

New Zealand is a case that does have some relevance.

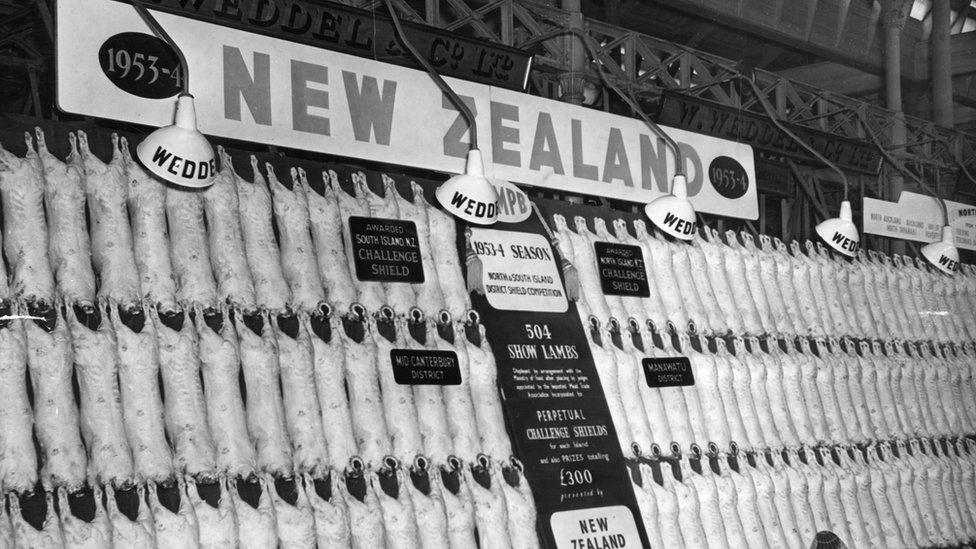

The UK was the major destination for New Zealand's main exports, such as lamb and butter, before 1973

In the aftermath of British accession to the EEC it lost preferential access to the UK market, something which was a legacy of its history in the British Empire and then the Commonwealth.

The Bank of England took a close look at the example when it tried to judge the likely economic consequences of various Brexit scenarios, external.

Before the UK joined the EEC in January 1973, it was the destination for 30% of New Zealand exports, amounting to 8% of the country's economic activity or GDP.

But from that point, New Zealand exporters faced the EEC's common external tariff. Agricultural exports are very important to New Zealand - most famously lamb, although dairy produce is now the country's biggest export earner. Food sales also had to contend with competition from subsidised European farmers.

Total export earnings fell in the first two years, investment grew more slowly and then declined from 1975. The economy went into recession in 1974.

After its exports to the UK faced higher tariffs, New Zealand focused on boosting tourism

Of course New Zealand was not the only economy to have a torrid time in the mid-1970s. There was a global recession linked to a rapid in rise in oil prices and disruptions to the international currency system.

So was anything different about New Zealand?

The Bank of England compared New Zealand with Norway and Austria. They had similar energy import needs (this was before Norway became a major oil producer) but they were not exposed to the fallout from the UK's accession to the EEC.

The Bank says GDP growth did not fall as far in either country and nor did inflation rise so sharply.

The Bank concludes that the evidence, "could therefore suggest the UK's accession to the EEC itself had a significant impact on the New Zealand economy".

How did the country respond to the turbulence?

Eventually New Zealand did find new markets. But overall economic growth did not return to pre-1973 rate until the 1980s.

New Zealand was the first Western economy to sign a free-trade deal with China

Today, the UK remains an important export destination for New Zealand. But it now comes behind Australia, China, the US and Japan. The most recent figures show the UK accounting for 4.4%, external of New Zealand's exports of goods and services.

Germany is also an important market for New Zealand, but for the most part its exports now go to countries in Asia or on the Pacific rim, countries that are relatively close (certainly closer than the UK).

What are the lessons for the UK?

New Zealand is just one case, so it needs to be viewed with some caution.

But it certainly does suggest that the sudden loss of preferential access to an important market can have very significant economic costs.

Of course there are differences between the situations faced by the UK after Brexit and New Zealand in the 1970s.

The share of exports facing possible challenges is greater for the UK (47% of goods exports last year) than for New Zealand in 1973 (30%). Including services brings the UK figure down to 43%

The "gravity effect" is the economic theory that countries trade more with their closest neighbours

The markets that New Zealand turned to after 1973 are closer geographically than the UK, where businesses faced new restrictions. In the case of Brexit the opposite will be true. Any markets that might offset any setback in commerce with the EU will be further away. That may make it more challenging.

The evidence does suggest that countries tend to trade more with economies that are closer or larger. It is known in economics as the gravity model and it has been described as "one of the most robust empirical findings, external in economics".

That said, there are economies outside the EU that are currently growing faster and are large, including the US, which is already an important trade partner for the UK. China and India are large and growing strongly although they are currently much less significant as British export markets.

And trade barriers now are generally lower than they were in 1973.

Does distance still matter for economic growth?

There are also some economists, notably Prof Patrick Minford of Cardiff University, who argue that the gravity model "does not fit the UK's trade history at all well, external". That, however, is a minority view.

The City of London is the major hub of the UK's financial services exports

The UK is also more of a services exporter than New Zealand. In 1972, services accounted for less than 15%, external of New Zealand exports. The figure for the UK, external now is 45%.

Some argue that selling services is less affected by distance - that the "gravity effect" is not so strong as is the case for goods. To the extent that is true, it could mean the fact that new markets for Britain will be more distant might not be quite so critical. That said, there is plenty of support, external for the idea that "gravity" does matter for services.

The UK today is obviously a substantially different economy compared with New Zealand's more than 40 years ago. The experience nonetheless provides some pointers about one of the issues the UK could face outside the EU.

- Published30 July 2019

- Published13 November 2018

- Published11 December 2018