Does the EU need us more than we need them?

- Published

"They need us more than we need them," has been a recurrent theme in the Brexit debate.

After the referendum, the idea has been used to suggest the government could have taken a tougher line in the negotiations over the terms of the UK's departure from the European Union.

Before the vote, it was used to suggest that the UK would have no difficulty retaining full access to the EU market, because it was in the EU's interests to allow it.

German carmakers were often invoked as likely allies in achieving that goal.

In early 2016, David Davis, then a Conservative backbench MP who was later the Cabinet Minister for Brexit, said, external: "Within minutes of a vote for Brexit the chief executives of Mercedes, BMW, VW and Audi will be knocking down Chancellor Merkel's door demanding that there be no barriers to German access to the British market."

What is the balance of trade between the UK and EU?

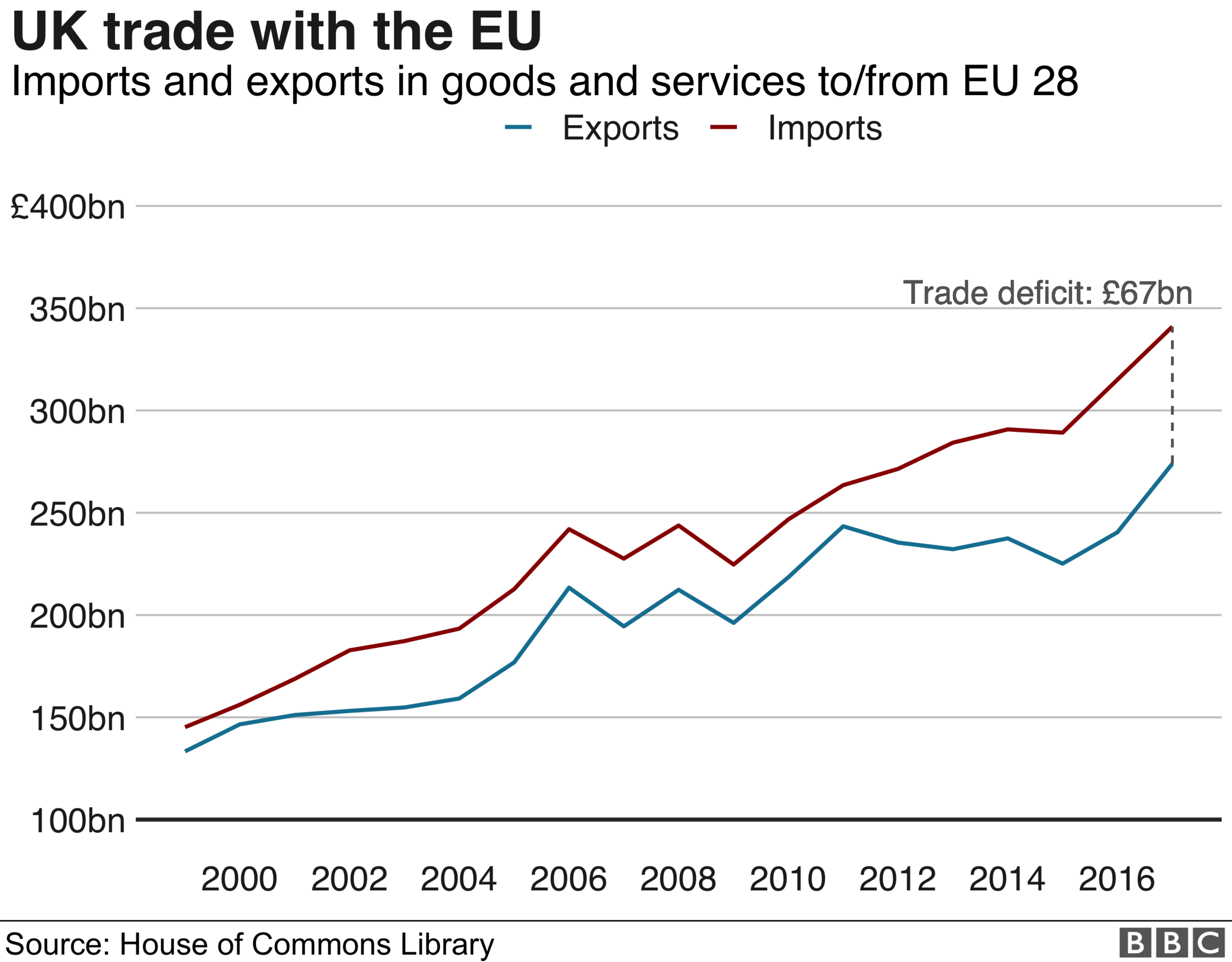

One central element (though not the only one) in the argument is the fact that the UK has a deficit in its trade with 27 EU member countries.

That is: they export more to the UK than the other way round.

So if there were new barriers to trade, the 27 have more sales of goods and services at risk than the UK does.

New barriers could arise as a result of a no-deal Brexit in the near term, or in a negotiated future relationship that gives less market access than currently prevails.

Even the much vaunted "Canada deal" with additions would involve some new hurdles for exporters to jump.

Depending on exactly what deal, if any, is achieved those barriers would include some combination of tariffs (taxes that are applied only to goods traded across borders), customs procedures and regulatory barriers, such as product standards and authorisation to provide services.

The basic facts of the trade balance are that yes, the UK certainly does buy more from the 27 than the other way round.

The UK had a bilateral trade deficit to the tune of £67bn in 2017. That breaks down to a larger deficit of £95bn for goods, but a surplus of £28bn for services.

So in total, the amount of exports potentially at risk from new trade barriers is greater for the 27 than for the UK.

But that is a rather crude measure of how much each side has to lose.

Let's take another example to illustrate the point.

What does Andorra have to do with Brexit?

The EU - with a population of more than half a billion and an annual economic activity or GDP of around £15 trillion - has a trade surplus with Andorra, external, which has a population of about 80,000 and GDP of less than £3bn.

Does that mean that the EU needs Andorra more than Andorra needs the EU? It would, of course, be an absurd suggestion.

Why? Because the EU's economy is so much larger.

For sure, disruptions to that trade would be a serious problem for some Spanish and French businesses and jobs near the border. But for the EU economy as a whole the impact would be tiny.

Now to state the obvious, the UK is not Andorra. It matters far more to the EU as an export market than Andorra does.

That said, a more revealing measure of what is at stake is to look at the amount of trade exposed to some risk of new barriers as a percentage of either a country's total exports or GDP.

Take goods first, as goods and services data is generally collected differently and is often published separately.

The EU 27 accounts for 48% of UK exports of goods, and 8% of GDP (in 2017, from the European Commission database, external).

When we look at the share of the EU's exports going to the UK there is a choice to make about whether to include trade among the remaining 27 EU countries in total goods exports. If we do include it, the UK share is 6.2%; if we don't it's 18% of the total. UK exports account for 2.3% of the EU 27 GDP.

You sometimes hear the suggestion that these figures miss an important point because the two biggest players in the EU, Germany and France, are the true political driving forces in the EU. So are they any more reliant on the UK market than the EU average?

For Germany, the figures are 6.6% of goods exports going to the UK, accounting for 2.6% of GDP. The latter figure is slightly above the EU average.

For France, the equivalent figures are 6.7% of exports and 1.4% of GDP, the latter comfortably below the average for the EU as a whole.

The countries that do have a relatively large exposure to the UK are Ireland, Belgium and the Netherlands.

And what about Germany's carmakers? They didn't show up for battle in the way David Davis hoped. The head of Germany's car industry association Matthias Wissman said, external last year: "however important the United Kingdom is to us as a market, the cohesion of the EU 27 and their single market are even more important to our industry".

That said, the UK would be a leading export market for the EU 27. For goods in 2017 it was very slightly behind the US, but well ahead of the next largest China. But it is important to remember: internal trade within the EU is really big for the 27.

Could the 'Rotterdam effect' complicate the picture?

There is a significant complication underneath these figures, sometimes known as the Rotterdam effect.

Exports are generally recorded as going to their first destination. So if a container goes initially to Rotterdam in the Netherlands (or Antwerp in Belgium or some other ports) and is then transferred for onward transport to somewhere else, it is nonetheless recorded as an export to (or an import from) the Netherlands (or another EU country).

It has proved impossible, external to quantify this effect with any real precision. It affects figures for trade going into the UK and out.

But even if we make some fairly extreme guesses about its magnitude, the UK still exports more as a share of its own GDP to the EU 27 than the other way round.

What about services?

For the services trade, external, the case is even clearer.

The UK economy is both smaller than the EU's and has a services trade surplus.

In 2016, services exports to the EU were 7.2% of UK GDP; for the EU 27 services exports to the UK were 1.1% of their GDP.

All these figures point in the same direction. The UK looks more exposed in the event of disruption to trade relations.

That is not to say the impact on the EU would be trivial, far from it.

The EU 27 would undoubtedly face significant economic harm from major disturbances to their trade with the UK. But on the basis of the trade data, the "they need us more" claim looks very shaky.

One point to add about the data. You may see figures elsewhere that are somewhat different. , external

There are inconsistencies in the way trade data are put together in different countries.

Some of the figures involve converting currencies and exchange rates vary. And there variations from year to year.

- Published19 December 2018

- Published14 December 2018

- Published20 December 2018