Energy price cap comes into force

- Published

A new energy price cap has now come into force - but householders can still get a better deal by shopping around, consumer groups say.

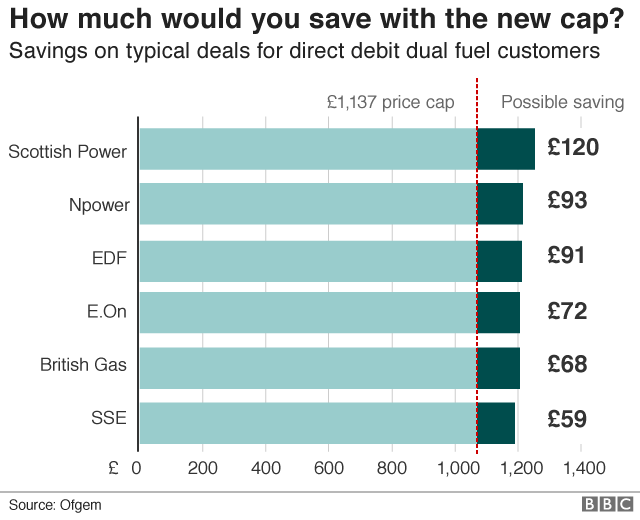

Regulator Ofgem has estimated that the new cap will save 11 million people an average of £76 a year.

Typically, the cap means that typical usage by a dual fuel customer paying by direct debit will cost no more than £1,137 a year.

Consumer organisations say that people could save more by switching suppliers.

"The introduction of this cap will put an end to suppliers exploiting loyal customers. However, while people on default tariffs should now be paying a fairer price for their energy, they will still be better off if they shop around," said Gillian Guy, chief executive of Citizens Advice.

"People can also make longer-term savings by improving the energy efficiency of their homes. Simple steps, such as better insulation or heating controls, are a good place to start."

How the cap works

Households in England, Scotland and Wales on default tariffs - such as standard variable tariffs - should be better off after the cap is introduced. Consumers in Northern Ireland have a separate energy regulator and already have a price cap. Those on a prepayment meter already have a price cap in place. Those who chose their tariff are ineligible.

Savings depend on how much energy is used in the household and how the bill is paid. The cap is per unit of energy, not on the total bill. So people who use more energy will still pay more than those who use less.

The cap is on the unit price of energy, and the standing charge. So the cost of electricity - for those on default tariffs - is capped at 17p per kWh. Gas is capped at 4p per kWh.

Dual fuel users will pay no more than £177 a year for a standing charge; electricity-only users will pay no more than £83, and gas users £94.

Ofgem will review the tariff in February, and then adjust it in April and October each year. It has said that the level of the cap is likely to rise in April 2019, to reflect the higher cost of wholesale energy. As a result, the average annual saving in 2019 is likely to be lower than £76.

The regulator will then judge the effect on the energy market in 2020, and the secretary of state will then decide whether to extend it by another year, or whether to end it at that time.

"The energy price cap can only be a temporary fix - what is now needed is real reform to promote competition, innovation and improved customer service in the broken energy market," said Alex Neill, from Which?.

What do the suppliers think?

Some have already changed the way they organise their tariffs.

Centrica - which owns the largest UK supplier, British Gas - has said that it will mount a legal challenge to the way the cap has been calculated.

It is applying for a judicial review against Ofgem, saying the regulator had set the threshold too low.

"Through this action Centrica has no intention to delay implementation of the cap, and does not expect the cap to be deferred in any way," the company has said in a statement.

"As we have previously said, we do not believe that a price cap will benefit customers but we want to ensure that there is a transparent and rigorous regulatory process to deliver a price cap that allows suppliers, as a minimum, to continue to operate to meet the requirements of all customers."

Will the cap lead to less switching?

Those who have argued against the introduction of a price cap have said it will be counter-productive, as it will lead to fewer people switching - where the potential savings are greater.

Which? has argued that some of the cheapest deals on the market have already disappeared, as suppliers needed to make up some of the money lost as a result of the cap.

It analysed deals priced at £1,000 a year or less for a medium energy user at the beginning of the year compared to now, and found there had been a sharp drop in availability.

- Published7 August 2018

- Published20 December 2018