Sweets industry stands firm against sugar backlash

- Published

The fair is the same size as 15 Wembley Stadium football pitches

The world's biggest trade fair for sweets is a Willy Wonka-esque display of tempting indulgences, but how is the industry adapting to a growing backlash against sugar?

Suddenly the nougat-covered pretzel I had for breakfast doesn't seem like such a good idea. It's 10:00 and I'm standing in the middle of a Technicolor palace of sugar.

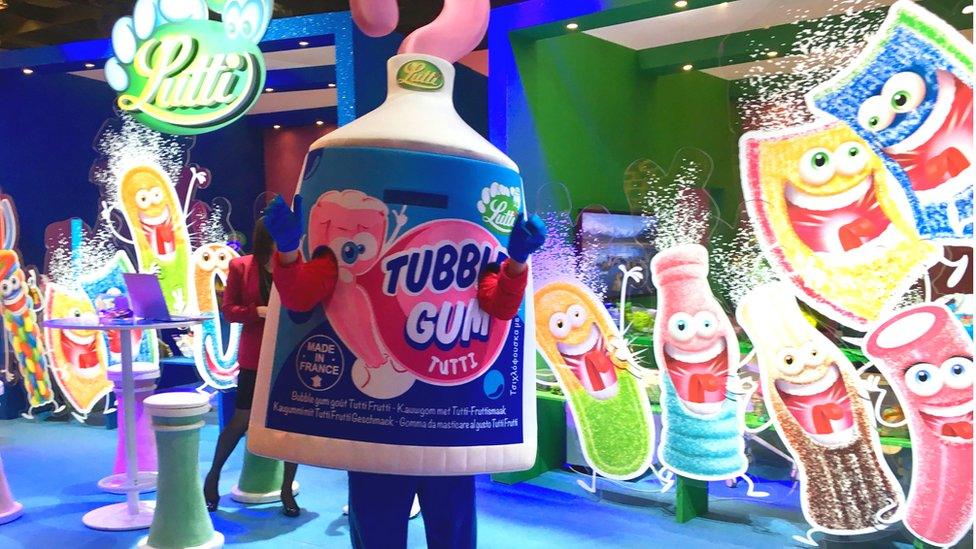

A human-sized fizzy bottle wiggles past, proffering a bottomless bucket of sweets but before I can take one, a man in a dark navy suit grabs a handful and then furtively glances around to see if anyone has noticed.

You could eat sweets for breakfast, lunch and dinner if you so desire

With 1,656 exhibitors there are plenty of different sweets to sample

He needn't worry because for four days, this nondescript convention centre in Cologne, Germany is home to the ISM sweets and snacks fair, the biggest of its kind in the world, which means it's candy for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

In what is now an annual homage to confectionery and snack foods, there are 1,656 exhibitors covering 110,000 sq m (1.2m sq ft) of floor space - the equivalent of about 15 Wembley Stadium football pitches.

Global chocolate sales last year totalled a whopping $109.5bn

People are opting to eat less, but better quality chocolate, say experts

The sheer scale of it is mind-boggling but perhaps not surprising when you consider that, according to market research company Euromonitor International, the global market for confectionery was worth $193.5bn (£148bn; €169.4bn) last year.

Chocolate sales alone were worth $109.5bn. But with food manufacturers under increasing pressure to reduce the sugar content of their products, what, if anything, are sweet firms doing?

Robbert Vos and Lennart de Jong, the founders of Dutch firm Hagelswag, are steadfastly ignoring the pressure, instead provocatively urging their customers to eat their chocolate for breakfast.

Chocolate for breakfast? Why not, says Dutch firm Hagelswag...

...it gives you a happy feeling all day long, the firm claims

Mr Vos says it's "the best way" to eat it "because you get a happy feeling for the rest of the day".

"Dutch people have been eating chocolate for breakfast for more than 100 years and most English people say it's like a dream come true. After the Netherlands, Americans and British people are our biggest customers," he says.

Having started the company in 2016 through a Kickstarter campaign to raise €30,000 (£26,000; $34,000), they now sell to more than 50 countries. But at €14.50 for a 250g bottle, it's not cheap.

Mr Vos, however, sees this as a selling point. "We use very high-quality chocolate, it's not a mass market product and people are willing to pay more for it."

White and milk chocolate are perennial favourites

But there are also lots of other different flavours to try

The readiness to splash out is symptomatic of wider consumer sentiment, according to Ivan Koric, senior food and drink analyst at Euromonitor International.

"In mature markets like Western Europe and North America, one of the strongest trends is 'premiumisation'. People are willing to spend more on a product they feel gives them added value," he says.

He adds that consumers in mature markets are choosing their snacks more carefully. "They're eating better but less. We call this 'mindful indulgence'. For example, people want to cut down on their sugar consumption."

Mushroom crisps - an unusual way to get one of your five-a-day

Chocolate with oats - a healthy treat?

Sami Nupponen is head of research and development at Finnish chocolate company Goodio. He thinks his firm's ChocOat line will appeal to a discerning, sugar-wary demographic.

"Our chocolate is made of 24% oats. Oats themselves have a bit of sweetness so it's an effective way of lowering the sugar content."

The labels also carry a panoply of other fashionable claims: organic, gluten free, vegan, no refined sugar and soy free. So which of these is most important to Mr Nupponen's customers?

"Vegan, followed by organic, but to be honest the chocolate's free from almost everything."

But what does the chocolate/oat combination taste like? I tried the Scandinavian favourite, liquorice-flavoured chocolate. It had a bit of extra bite, but otherwise wasn't much of a departure from regular chocolate.

Like Hagelswag, the product is more expensive than many other brands - a 10-pack of 25g ChocOat liquorice bars is £17.49 - but the high price tag doesn't seem to be doing Goodio any harm. Last year it turned over €1.5m euros and Mr Nupponen is expecting that to grow to more than €2m in 2019.

Cheaper sweets such as gummy bears are also on display

There are also traditional favourites such as nougat

While many small, new confectionery companies use novelty to set them apart, some of the venerable old timers have to use different tactics to keep ahead of the game.

A couple of traditional candy makers have not jumped on the health trend and are sticking to regular sugar.

Marzipan company Niederegger was founded in the German city of Lubeck in 1806 and its product is based on two main ingredients, almonds and sugar.

"In over 200 years we've never changed the recipe," says Niederegger spokeswoman Kathrin Gaebel. The company ethos seems to be more about adaptation than revolution.

"We watch trends and introduce around 50 flavours a year. Recently we've added double chocolate and marzipan with white chocolate pieces. A lot of our new ideas come from customers and if they come up with something that could work, we develop it," she says.

Many firms are emphasising their wholesome ingredients

But not all firms are cutting back on sugar

But what if those suggestions include altering the fundamental recipe, for example, the sugar content? This is non-negotiable.

"In Germany there's a rule on producing the raw paste for marzipan: it has to be two thirds almonds to one third sugar," says Ms Gaebel.

And regulations aren't the only thing that get in the way of changing the basic process.

"If you lower the sugar, the structure of the marzipan changes. The almond needs sugar during the roasting process in order for it to work. So I think marzipan will stay the same for the next 200 years."

Despite the demonisation of sugar and worries over obesity, it seems like our appetite for the sweet stuff is as strong as ever.

All photographs by Elizabeth Hotson.