Flybmi won't be the last airline failure, say analysts

- Published

- comments

Flybmi won't be the last airline to collapse, analysts say

In two short sentences, Flybmi's announcement that it had collapsed summed up the airline industry's woes: fuel costs, green taxes, Brexit uncertainty, falling passenger numbers. It might have added fierce competition, but that is probably a statement of the obvious.

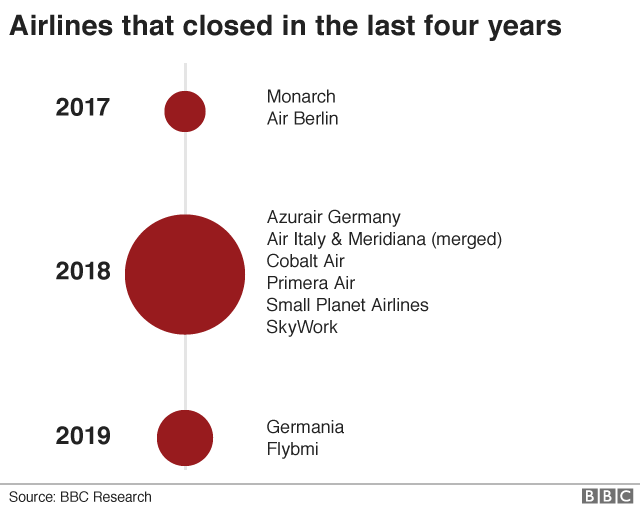

Several European airlines have folded or hit financial trouble during the past two years. Britain's Monarch collapsed in October 2017, while Germany's Germania filed for insolvency earlier this month.

Air Berlin and Alitalia went bust, although the latter was propped up by the Italian government.

Primera, Cobalt, Azurair Germany, Small Planet Airlines and SkyWork may not be household names, but all succumbed to the market turbulence sweeping across the sector.

UK regional airline Flybe came close to folding and put itself up for sale. And last month Norwegian Air Shuttle was forced to seek an emergency cash injection, putting a question mark over its promise to revolutionise budget long-haul travel.

Ryanair boss Michael O'Leary may be prone to a bit of hyperbole, but when he warned this month that the industry would see more bankruptcies no one doubted him.

"Winter is the worst time of year for airlines," says Ascend Consultancy analyst Peter Morris. "If you can get through the winter there's a chance of getting summer bookings."

So why are so many airlines failing?

Travel expert Simon Calder went to the heart of the problem when he told the BBC that the airline industry's problem is: "There are simply too many seats and not enough people."

But the reasons for this are many and complex.

The growth of airlines in Europe, mainly budget carriers, came on the back of deregulation and an explosion of route networks.

Using new and cost-efficient aircraft operators started new services. If one route failed, they tried another. Flexibility was key.

According to the International Air Transport Association, the number of flights in Europe has risen more than 40% compared with a decade ago. At the same time, though, fares have fallen, squeezing margins and reducing financial room for manoeuvre.

This expansion has not insulated the industry from wider shocks, such as economic slowdown, rising oil prices, and unfavourable exchange rates - the depreciation of sterling has made it more expensive for Britons to go abroad.

And there are unexpected extra costs - from traffic control strikes, maintenance bills, bad weather (remember the Beast from the East) and passenger compensation.

New EU passenger compensation rules were, said Wizz Air boss József Váradi, becoming a real burden on airlines. He cited this, along with fuel costs, as the two biggest squeezes on airline profitability.

Oil prices rose and slumped in 2018, and since the start of the year have been on their way back up. Fuel costs have been cited as a factor in almost all the problems reported by airlines in the last couple of years.

Cash-strapped Flybe put itself up for sale

Flybmi also highlighted another extra cost that did damage - emissions taxes. Tim Jeans, a former managing director of Monarch and chairman of Newquay Cornwall Airport, agrees that it is becoming a serious issue for the whole industry.

"Carbon costs are a creeping cost for all airlines," he told the BBC. "The fees you need to pay to carry out your flying are going up all the time, and they are now quite a material cost."

He thinks many airlines have not fully budgeted for this rise. "It certainly looks like that is the case with Flybmi," he said.

There's also the issue of Brexit. Critics say it has become convenient for UK companies to blame uncertainty around Britain leaving the EU for their problems.

But for any UK airline - from Flybmi to British Airways - the potential unravelling of Europe's open skies agreement that has existed for decades is a real worry, Mr Jeans says.

It will certainly hinder the ability of some airlines to do deals and offer services if there is uncertainty about their freedom to fly across Europe, he said.

Ryanair's Michael O'Leary warned of more casualties in the airline industry

Mr Morris says problems at International Consolidated Airlines (IAG) underline how Brexit is worrying the major carriers.

To retain its operating licence in Europe, IAG, which owns British Airways and Iberia, must show it is more than 50%-owned and controlled by EU investors. So, IAG is capping non-EU investment - except for UK shareholders, who will be counted as part of the EU even after Brexit.

It's an example, says Mr Morris, of "how even the big boys might have some problems with the aviation environment".

Will there be more airline failures? "Yes, I think definitely," says Mr Morris.

Airlines that are particularly vulnerable are the smaller carriers squeezed between the major players like BA and Lufthansa, and the big low-cost carriers like Ryanair and Easyjet, Mr Morris says.

The former have economies of scale and a presence at major hub airports like Heathrow. The latter operate larger, more efficient aircraft and more regular services, so have lower per-seat costs. It means both sectors can better withstand shocks.

Mr Jeans agree. "Flybmi's demise is a perfect example of just how difficult it is to make money in that middle ground," he says.

- Published17 February 2019

- Published7 February 2019

- Published7 February 2019

- Published5 February 2019

- Published4 February 2019