When class sizes fall so does teachers' pay

- Published

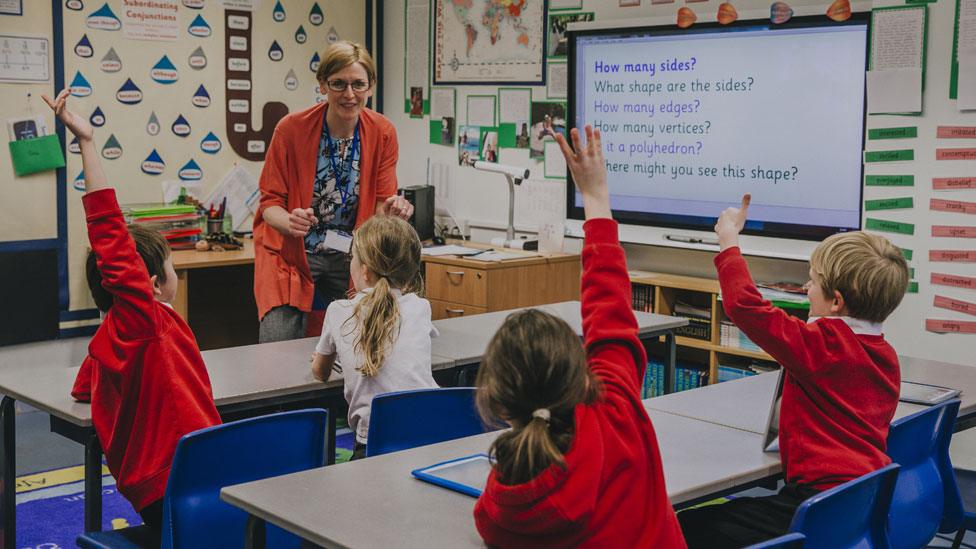

Making class sizes smaller sounds like a success story.

But an international analysis of its impact shows unintended consequences - it often seems to mean lower pay for teachers and there isn't much evidence that it brings better results.

Reducing class sizes has been a popular policy in many countries, often supported by parents, politicians and teachers.

It has been one of the big trends of the last decade.

Class sizes fell on average by 6% between 2006 and 2014 in the lower secondary school years in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

This includes more than 30 of the most developed countries, including most of western Europe, Japan, Australia and the United States.

Smaller classes, more teachers

The expectation was that smaller class sizes would mean a more personalised education, with improvements in behaviour and learning.

High-ranking education systems in East Asia often have big class sizes

And when all other factors are equal, test results show there are better outcomes from smaller classes.

But when it comes to investing in schools there are always trade-offs - and countries can only spend their money once.

When education budgets are focused on cutting class sizes, the figures show there are usually reductions elsewhere - in particular in lower increases in teachers' pay.

Across a whole education system, smaller class sizes result in a greater number of classes, which require more teachers to lead them, which in turn means higher costs.

As well as needing more teachers, cutting class sizes can also mean building more classrooms and expanding schools.

Spending choices

For the first time, the OECD has quantified those trade-offs, external - and their magnitude is surprising.

To offset the cost of cutting the average class size by just one student, teachers' salaries would need to decrease by more than $3,000 (£2,320) per year in more than half of countries in the OECD.

Cutting class sizes has been a popular international trend in recent years

In Switzerland and Germany it would mean cutting pay by more than $4,000 (£3,100) and more than $3,000 (£2,320) in countries including Austria, Norway, the United States, Finland, Australia, Spain and the Netherlands.

Teachers' salaries represent a major part of school spending and any measure that is going to increase the number of teachers will soon have a big impact on education budgets.

The trade-offs of reducing class sizes are showing up in the bigger picture.

Teachers in the lower secondary school years are now paid only 88% of what other full-time graduate workers earn.

Recruitment problems

If teachers' salaries are not competitive, there will be problems of recruitment and a risk that they will leave the profession for jobs which are more highly compensated.

Between 2005 and 2015, teachers' pay across the OECD increased on average by only 6% after inflation.

The cost of smaller class sizes could be that there is less money to invest in teachers

In a third of OECD countries there was a real-terms decrease in pay.

There can be other national and economic factors affecting teachers' pay - such as the financial crash and policies on public-sector pay.

But cutting class sizes will still mean taking money that could have been spent elsewhere.

There could be other options. Teachers could work for longer hours in the classroom and reduce their preparation and non-teaching time. Or there could be a reduction in lesson time.

But getting a balance from this would have a heavy price tag. In some countries it would mean cutting students' instruction time by almost 70 hours per year to save the extra cost of recruiting more teachers to reduce class sizes.

Better results?

Is reduced class size worth these costs?

There is no clear link between education systems with smaller classes and better learning.

Results from the latest Pisa tests show no association between average class size and science performance.

In fact, East Asian countries such as Singapore and China often top the rankings both in terms of performance and in having the biggest class sizes.

The science results, perhaps unexpectedly, show higher scores for students in larger classes and in schools with higher student-teacher ratios.

Perhaps this is a question of degree - and there might need to be a significant reduction in class size to have a positive impact.

But it seems whenever high-performing education systems have to make a choice between smaller classes and investments in teachers, they go for the latter.

Of course, there could be other political and economic decisions, such as more funding for schools, so that the number of teachers and their salaries could both be increased.

But given that budgets are often constrained, this study shows how spending choices can have unanticipated outcomes.

Reducing class size is a costly measure, so it's worth considering the benefits against other policy choices.

If this was a financial decision how would you get more bang for your buck?

How would it compare with spending more on increasing teachers' salaries, investing in teacher training or changing the curriculum?

Could cutting class sizes, seen as such a popular policy, come at the expense of the quality of teaching?

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is Sean Coughlan (sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk).