Could a computer ever create better art than a human?

- Published

This portrait was created by computer, so is it really art and is it any good?

Last year a portrait of Edmond Belamy sold for $432,000 (£337,000).

A bit steep, you might think, for a picture of someone you've never heard of. And you won't have heard of the artist either, as the picture was created by an algorithm drawing on a data set of 15,000 portraits painted between the 14th and 20th Centuries.

And to be honest, it's a bit rubbish.

The sale, which astonished auction house Christie's, raised many important questions. Can a computer, devoid of human emotion, ever be truly creative? Is this portrait really art? Does any of that matter if people are prepared to pay for it?

And as artificial intelligence evolves and eventually perhaps reaches or surpasses human level intelligence, what will this mean for human artists and the creative industries in general?

Algorithms have already created artworks, poems, and pieces of music, but are they merely mimicking rather than creating? Cognitive neuroscientist Romy Lorenz says a lot depends on how we define creativity.

Chinese Go player Ke Jie was eventually defeated by DeepMind's AlphaGo AI program

If creativity means finding completely new ways to solve problems, then AI has already achieved that, she argues, citing Google's DeepMind subsidiary.

In 2017, one of DeepMind's AI programmes beat the world's number one player of Go, an ancient and highly complex Chinese board game, after apparently mastering creative new moves and innovative strategies within days.

"Google would say that was creativity - new ways of finding solutions that it was not taught," she says.

But is art more than just creative problem-solving?

Games, particularly those which take place within virtual worlds, have been the perfect setting for AI to solve problems creatively.

But asking an algorithm to create without any human input at all actually yields quite boring results, argues New York-based professor of computer science, Julian Togelius.

He cites Kate Compton's "10,000 bowls of oatmeal" problem, external, which suggests that while algorithms can now create infinite worlds, these can be tedious for humans to play in.

An example, he suggests, was the hotly-anticipated release of space exploration game No Man's Sky, which offered 18 quintillion algorithmically-generated planets to explore.

No Man's Sky uses "procedural generation" to create new worlds automatically

"In No Man's Sky there are more places you could visit in a lifetime, with different flora and fauna. But that game has had mixed reviews - it's a technical masterpiece but it's not super interesting to play," he says.

"The question is, can your algorithm generate a world that has meaning to it, and that is particular to the player in terms of place or skill?

"These algorithms are amazing - they can do more and more. But there will always be things us humans want to put in. It's the power of the sensibility and intentionality of the human brain - that's what is hard [to recreate]."

Dr Lorenz points out that true artistic creativity differs from creative problem solving in that it requires a shift in perspective that machines do not appear to have the capacity for.

Romy Lorenz says AI has no "internal world" from which to create true art

"Artistic creativity is about turning an introspective thought into a medium, whether it's a sculpture or a piece of music. It's about taking an abstract form and making it concrete.

"But AI has no internal world and it has no need to create its desires or fears."

So rather than letting AI take complete control, results seem to be far more fruitful when human artists work hand-in-hand with machines.

Musician and University of Sussex lecturer Dr Alice Eldridge suggests that we should treat AI as "just another tool that we have designed, like the wheel, or the combustion engine".

Dr Alice Eldridge (l) and Dr Chris Kiefer (r) play their self-resonating feedback cellos

She has helped create a cello that uses a combination of acoustics, electrification and an adaptive algorithm that makes the instrument self-resonate; or essentially, play itself.

"With a classical cello you have to bring the instrument alive with a bow; a feedback cello is already singing, your job as a performer is to shape the sound - it's more like a dance than 'controlling' an instrument in the traditional way," she says.

"This creates a different way of thinking about, and designing our relationships with, musical instruments, and technology in general."

Mick Grierson, at the UAL Creative Computing Institute in London, believes advances in AI will "lead to better art, new types of artists and new mediums".

In 2016, Nordic band Sigur Rós used his software to create a constantly evolving version of one of their singles, external, which the band played on a 24-hour road trip around Iceland.

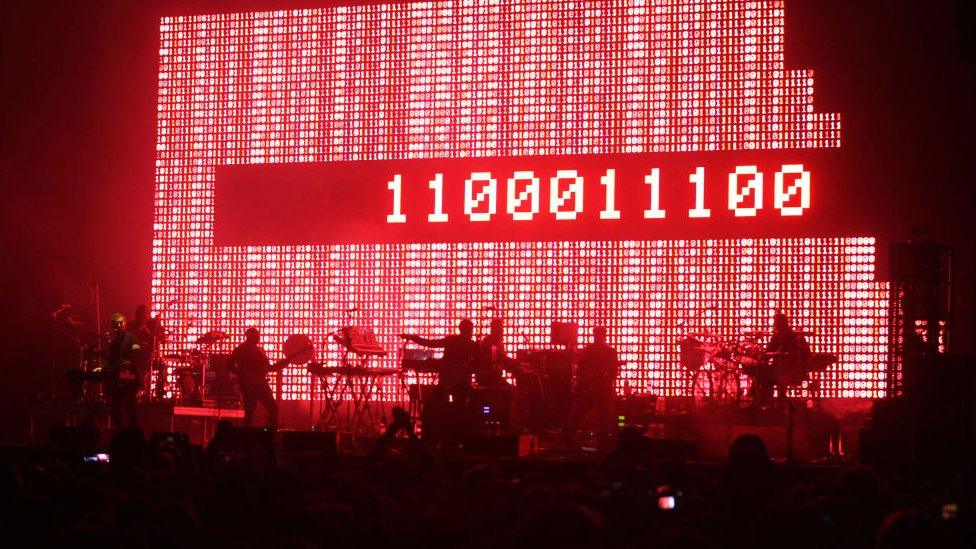

The band Massive Attack have been experimenting with AI to create unique pieces of art

Individual musical elements of the song were fed through the software to make a song that, like a live performance, is subtly different with every repetition, and could respond to external prompts.

Innovative composer and producer Brian Eno, who has worked with Roxy Music, David Bowie and Coldplay amongst others, is also a big fan of using algorithms to create music that constantly changes.

Prof Grierson has also worked with Massive Attack on an AI reworking of their Mezzanine album, external, to mark its 20th anniversary. The album will be fed into a form of AI that teaches itself - a neural network - and visitors to an upcoming Barbican exhibition, external will be able to affect the resulting sound by their movements.

While AI could be seen as yet another threat to artists' livelihoods, he believes machines will never come close to competing.

"AI could be used to reduce human creativity by people who want to make money - but it's people [not technology] who are responsible for doing that.

"The technology is never going to be good enough to generate better culture than people who use it to create their own."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebooko, external