Gender pay gap: Can it be fixed?

- Published

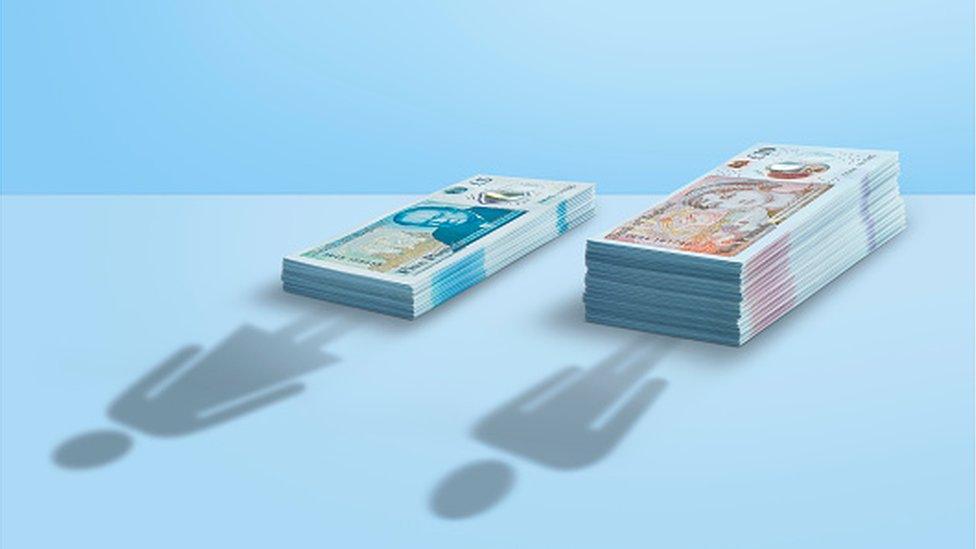

Why do women continue to earn less than men, despite efforts to redress the imbalance?

The latest figures on the difference between what companies pay men and women have been revealed.

Three-quarters of firms pay men more than women. That's based on data so far from 10,000 firms required by the government to release the information.

The gender pay gap is calculated by taking all employees, external in an organisation and comparing the average pay between men and women.

This is the second year that companies have had to report. All UK firms with 250 or more employees must disclose their pay gaps around this time of the year.

This is not the same as equal pay, which is the right for men and women to be paid the same for the same, or equivalent, work or work of equal value.

That is illegal, and has been for over 40 years.

But there is still a huge gulf between the average pay earned by women at these companies and their male colleagues.

Why is this?

TUC boss Frances O'Grady says there are many reasons why the gender pay gap continues

"There are many reasons why it exists," says Frances O'Grady, general secretary of the TUC federation of trade unions. "Some are to do with work, such as undervaluing the jobs traditionally done by women, a lack of genuine flexibility for employees at work, and too few good-quality part-time jobs.

"Others are about caring responsibilities, with women still undertaking the majority of childcare."

It can be fixed, she says, although the TUC has calculated that at the current rate, it will take around 60 years to achieve pay parity between men and women.

"Making employers publish information on their gender pay gaps is a start but it's nowhere near enough," she says.

"Employers must be legally required to publish an action plan to say how they'll tackle pay inequality at their workplaces and advertise jobs on a more flexible basis."

Better pay for part-time work and care jobs are needed, as well as more flexible jobs, she says. "Workplaces that recognise unions are more likely to have family-friendly policies and fair pay."

She also argues for more childcare and elder care, better careers advice, and more flexible working as a way to help women.

Alice Hood, head of equality and strategy at the TUC, adds that while pay discrimination is illegal, it still exists.

The New Economics Foundation's Alice Martin says many women prefer flexible working

Increasing numbers of women are moving into self-employment, partly drawn by the potential of a more flexible approach to work, says Alice Martin, head of work and pay at the New Economics Foundation think tank.

"But flexibility doesn't always mean autonomy over pay and time: the gender pay gap persists even for women in self-employment," she says.

In 2016, full-time self-employed men earned £120 more a week than women - £363.

Jobs typically done by more women than men, such as foster care, domestic labour, or even sex work, often have fewer opportunities to band together to ask for more pay, says Ms Martin.

Childcare support and a shorter working week could be solutions, she says.

"Women are still far more likely to perform essential unpaid labour outside of work. They do 60% more unpaid work than men. This means that they often have to find work which enables them to care for children or elderly parents. This locks people, mainly women, outside of secure, well paid work."

The CIPD's Charles Cotton says secrecy over pay rates helps perpetuate the gender pay gap

Charles Cotton is from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), an organisation that helped shape pay gap regulations.

He also advocates flexible working, but says pay secrecy and pay history are helping to keep old, bad trends going.

Employers can help by not asking for previous salary history in the recruitment process, he says. More women should be included in promotion shortlists; there should be greater transparency over pay decisions; and firms should offer more family-friendly benefits, he argues.

"However, some of the gender pay gap is due to what is going on outside the workplace," he says, such as "societal assumptions about what constitutes male or female work".

And he agrees with other commentators that a shortage of child or elder care is a key issue.

"If we are going to see progress, we need government action, and to challenge assumptions about what both women and men can do."

The Equality Trust's Wanda Wyporska says old-fashioned sexism is still an issue in many firms

Many of the best-paying jobs at big companies are on the board, and less than a third of board members at the top-100 publicly-traded firms are women. Chief executives are even rarer: there are just five women leading FTSE 100 companies.

"Companies have incentives to drive that remuneration up," for big bosses because of the way that pay is decided, says Dr Wyporska.

So when these mostly male bosses receive big pay rises, it only exacerbates the pay imbalance, says Wanda Wyporska, executive director at The Equality Trust, a charity that campaigns to reduce social and economic inequality.

"If you have a CEO on £1m and some staff on the living wage, that will have a huge impact," she says.

Companies that outsource the poorest-paying jobs, like cleaning and support staff, can have a significant impact on the data, says Ms Wyporska.

And overlapping pay bands can conceal pay iniquity. A senior woman may be paid at the bottom of a management band but be paid less than a man earning at the top of a more junior band.

At the heart of the matter of why so few women are in the most senior - and best-paying - jobs is often old-fashioned sexism, Dr Wyporska argues.

The government-backed Hampton-Alexander Review into gender imbalance heard some executives say: "I don't think women fit comfortably into the board environment" and "most women don't want the hassle or pressure of sitting on a board".

And finally, bonus gaps are frequently twice the size of pay gaps, and are not infrequently in excess of 50%, according to data from the Equality Trust which analysed awards at FTSE 100 firms.

- Published31 May 2018