Boeing safety system not at fault, says chief executive

- Published

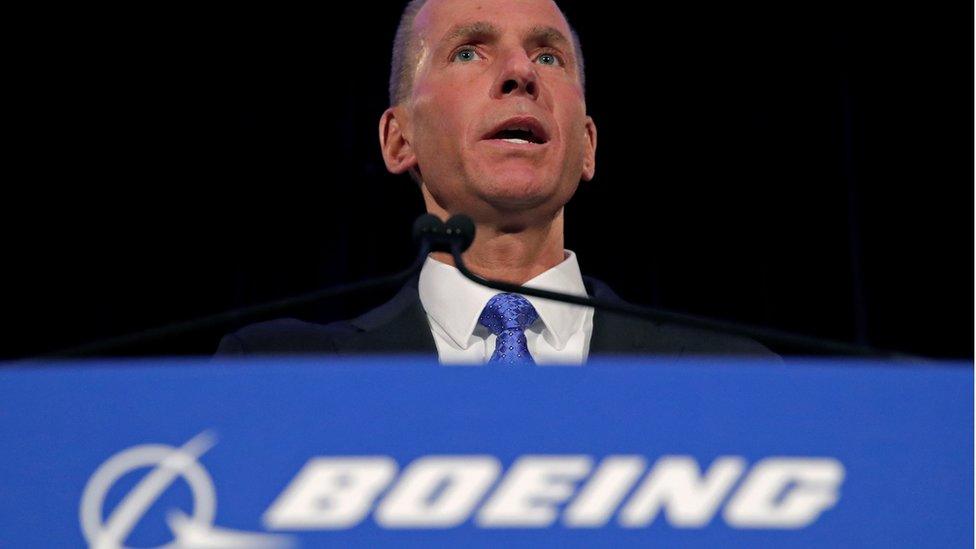

Boeing chairman and chief executive Dennis Muilenburg

Boeing's boss has refused to admit that a system introduced in its 737 Max 8 aircraft was flawed following two fatal plane crashes.

Appearing in front of investors and the media, Dennis Muilenburg maintained the system was only one factor in a chain of events that led to the disasters.

But new reports have raised fresh questions about the plane's safety.

It has emerged that whistleblowers connected to Boeing contacted the US airline regulator about the system.

Meanwhile, the Wall Street Journal revealed, external that Boeing failed to activate a safety feature linked to sensors on 737 Max planes bought by its biggest customer, Southwest Airlines.

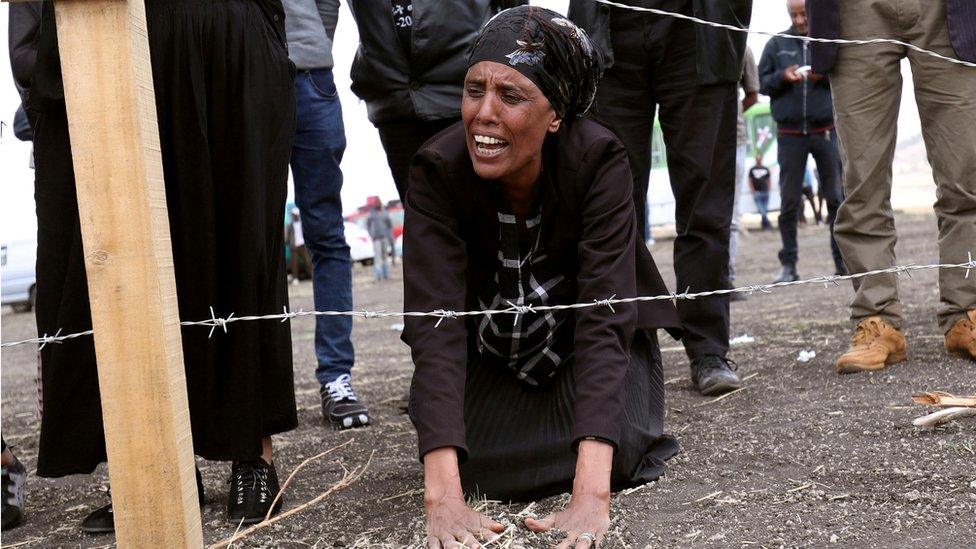

The 737 Max is grounded worldwide after an Ethiopian Airlines flight crashed near Addis Ababa in March, killing all 157 people on board.

It follows a crash by Lion Air in Indonesia five months earlier, which claimed 189 lives.

'Chain of events'

Facing shareholders and the media for the first time since the Ethiopian Airlines tragedy, Mr Muilenburg acknowledged that a common factor in both accidents was faulty data from a sensor triggering the plane's Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) at the wrong time.

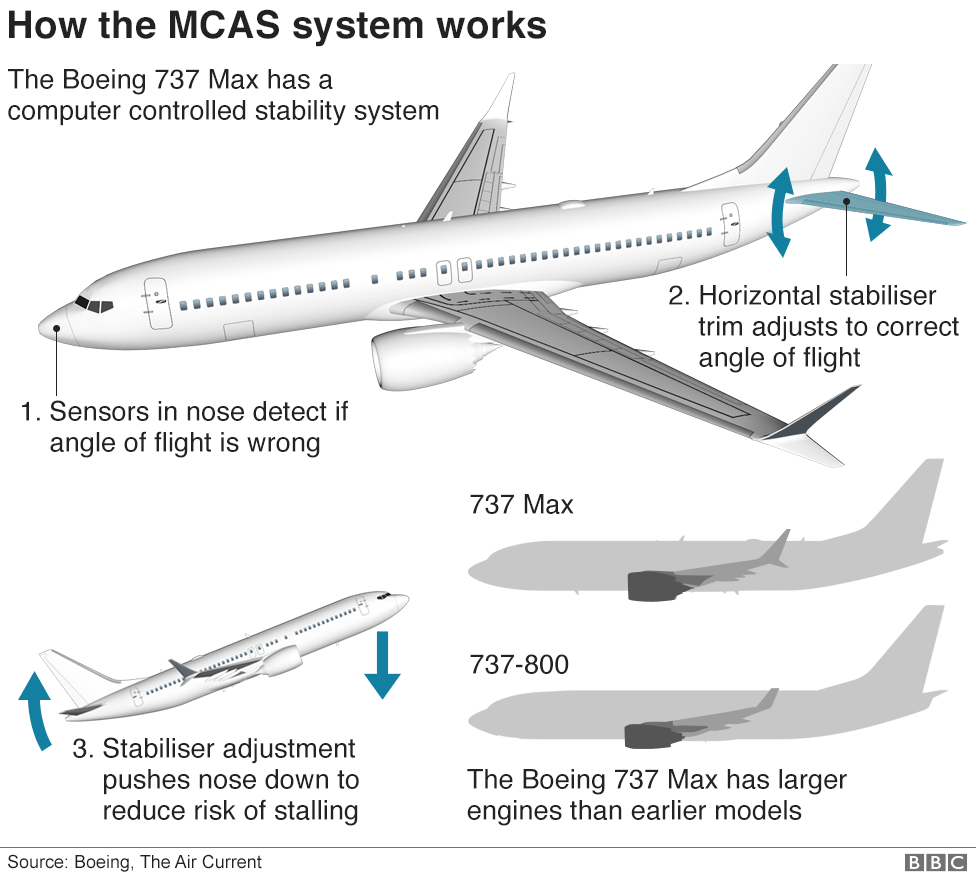

The system is designed to improve the handling characteristics of the aircraft and improve stability when the nose is pitched up at a high angle. It was a new addition to the 737 Max when the aircraft was launched in 2017, and was designed to make the aircraft more like the previous generation of 737 to fly.

It works by trimming the nose of the plane downwards. In both accidents, it appears to have activated when the pilots were trying to gain height, depriving them of control.

However, Mr Muilenburg said that the MCAS system met its "design and certification criteria" and pointed to a number of other scenarios that may have contributed to the fatal accidents including actions taken or not taken by pilots.

He added: "As in most accidents, there are a chain of events that occur. It is not correct to attribute that to any single item."

A preliminary report into the Ethiopian Airlines flight found that the plane nosedived several times before hitting the ground.

In the case of the Lion Air flight, a report suggested that the system malfunctioned and forced the plane's nose down more than 20 times before it plummeted into the sea.

Boeing has developed and is testing a software update for MCAS.

Mr Muilenburg's comments came after it emerged that several whistleblowers had contacted the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) after the Ethiopian Airlines crash to voice concerns about the company's manufacturing processes.

One of them reported having seen damage to wiring used by a vital sensor aboard the aircraft - the same sensor that has been implicated in both crashes. An FAA spokesman said the allegations were under investigation and had not been officially substantiated.

Boeing has also come under pressure over the information available to pilots aboard the aircraft, after one of its major customers, Southwest Airlines, told US media it had not been informed that a warning feature previously offered as standard on the 737 had become a paid-for option on the new model.

The feature was a so-called "AOA Disagree" alert, meant to inform pilots of significant discrepancies between the information provided by two angle-of-attack sensors in the nose of the aircraft. This would provide a warning if one of them was faulty.

The angle of attack sensors are used to determine the angle at which an aircraft encounters the airflow over it. On the 737 Max, the flight computers relied on data from a single one of them to decide when to activate the MCAS system, and a sensor failure is believed to have been a factor in both crashes.

Southwest told the Wall Street Journal it had not been made aware that the warning feature was not available as a standard item until after the Lion Air crash in October.

Mr Muilenburg maintained early on Monday: "We don't make safety features optional."

A family member of the Ethiopian Airlines crash victims mourns at the fenced-off accident site

In a later statement, Boeing then said: "The disagree alert was intended to be a standard, stand-alone feature on Max airplanes. However, the disagree alert was not operable on all airplanes because the feature was not activated as intended.

"The disagree alert was tied or linked into the angle of attack indicator, which is an optional feature on the Max. Unless an airline opted for the angle of attack indicator, the disagree alert was not operable."

It said that once the 737 Max 8 returned to the skies, it would have "an activated and operable disagree alert and an optional angle of attack indicator".

The angle of attack indicator is another instrument available to pilots, designed to warn of a possible aerodynamic stall.

Customer pressure

Boeing has already seen a $1bn (£773m) drop in revenues related to the 737 Max crisis, while some customers have reviewed their orders.

On Tuesday, Virgin Australia said it had reached an agreement, external with Boeing to defer deliveries of 737 Max aircraft.

In a statement, the company said it would delay first deliveries of Boeing Max 737 jets from November 2019 to July 2021.

"We will not introduce any new aircraft to the fleet unless we are completely satisfied with its safety," Virgin Australia Chief Executive Paul Scurrah said.

- Published28 April 2019

- Published24 April 2019