Online political ads 'need law change'

- Published

Are the UK's election laws fit for the era of digital campaigning? The Electoral Commission certainly does not think so.

The watchdog has called for a change in the law to make online political adverts show clearly who paid for them.

It wants online adverts to carry the same information as printed election material, which has to say who has produced it.

The director of regulation at the Electoral Commission Louise Edwards told me a new law was needed to make sure that it was clear who had paid for online advertising and make spending on digital campaigning far more transparent.

"What we need and what we're calling for, is a very clear change in the law to make parties and campaigners say on the face of their advert, who they are, who's paid for that advert and who is promoted," she said.

Impatient?

She says the Electoral Commission first recommended these changes in 2003 and is waiting for the outcome of a government consultation on the issue.

When I asked whether the regulator's patience was running out, she paused: "Impatient? These are things we think are important and we'd like to see them in place."

The government said it has committed, external to putting in place a digital imprint regime and technical proposals will be published later this year.

That will come too late for the European elections, in which the UK now looks certain to participate.

The regulator says online campaigning is becoming ever more significant in the UK, with spending doubling between the 2015 and 2017 General Elections.

Facebook criticism

Facebook has recently started an online archive of political adverts on its site, with information about who is behind them and how they are targeted. Louise Edwards says that is a start but more information is needed on the adverts themselves.

The social media giant has opened an operations centre in Dublin to oversee its impact on the European Parliament elections.

It has faced criticism for its role in spreading misinformation and enabling foreign intervention in elections. The company says the poll in 28 countries is the most complex challenge its election monitoring team has yet faced.

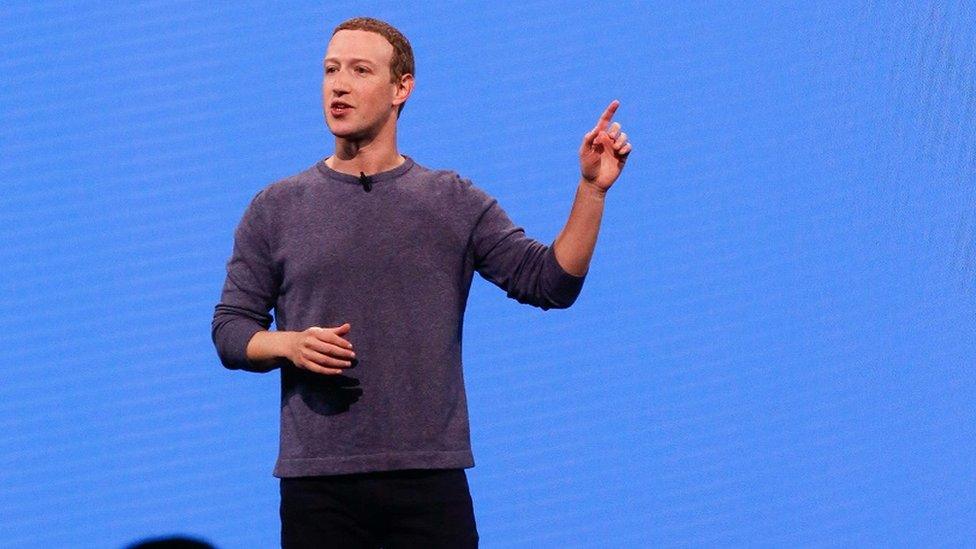

Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg

"What we've learned over the last few years is that there are various threats to the democratic process," says Facebook's vice president for global security Richard Allan. "And we're absolutely determined to try and minimize the risk of those threats as far as we can."

Amongst the threats that Facebook has identified are voter suppression, where voters are deliberately given false information about where and when an election is taking place, and networks of fake accounts created by those trying to interfere in the democratic process.

Between October 2017 and September 2018 Facebook shut down 2.8 billion fake accounts. The company says people trying to abuse its systems often set up a computer which creates a new account every 10 seconds and it is engaged in a "constant war" to remove them.

After the 2016 US Presidential election, Mark Zuckerberg said it was "a pretty crazy idea" to think fake news on Facebook had played any role in Donald Trump's victory.

Positive force

Later, he admitted he had been wrong to underplay the threat after it emerged that a Russian organisation had spent heavily on Facebook adverts promoting division during the election.

Now Mark Zuckerberg's company is trying to show that it can be a positive force in the democratic process. I put it to Richard Allan that, given the catalogue of harms we have seen coming from Facebook, we might be better off if it just removed itself from elections.

He disagreed, admitting that bad actors had exploited the openness of the network but stressing that millions used it to engage with political issues in positive way: "We believe that we can actually have the healthy democratic debate while minimizing these unhealthy attempts to interfere with it."

Facebook has set about trying to regulate political activity on its hugely powerful platform. But the Electoral Commission thinks it is high time the government realised that its job is to bring what it calls our archaic and complex electoral laws into the digital era.