Would you buy shares in Uber?

- Published

- comments

For sale: shares in a company that has already burned through $27bn (£20.7bn; €24bn) in cash, will burn through tens of billions more of its new shareholders' money, has never made a profit and won't for many years - if ever.

Sounds too bad to be true, but that is precisely what is on offer when Uber shares start trading today.

It seems impossible to imagine why anyone would want to buy them, and yet market watchers expect there to be no shortage of people queuing up to buy a slice of a company whose name has become a recognised noun in dozens of languages around the world.

Uber is selling shares to finance one of the most ambitious business plans in history. To revolutionise and then dominate global transportation.

This company is about much more than getting a car home after the pub when you don't fancy public transport. Uber wants to dominate food delivery, electric bikes, international freight and more.

Lyft shares have fallen sharply since their listing on Nasdaq

That makes Uber a different animal from Lyft, its ride-hailing rival which has seen its shares fall 25% since it first sold shares publicly.

The most important part of Uber's business plan is scale. Spend whatever it takes, for as long as it takes to smash the competition.

This was Amazon's plan. Amazon didn't make a profit until six years after it first sold shares. It spent every dollar of revenue - and more - in expanding its business. It worked. Amazon's market share of e-commerce in the US is now double the next biggest nine companies combined.

Landlord or peasant?

As astonishing as that is, Uber has the potential to have an even greater impact.

It is the poster child of what is known as the gig economy. It provides a platform to match individual service providers/contractors (Uber drivers) with customers - taking a hefty slice (currently 25% in the UK) for matchmaking.

Some fear that if Uber succeeds in making its platform the dominant mode of transport around the globe, then it will have become the digital equivalent of a feudal landlord.

It owns the land on which the workers toil like peasants for low wages, while the economic spoils go to the landowner - dramatically skewing the returns of economic activity towards capital rather than labour.

And if and when driverless cars come along, that will eliminate the return to labour completely.

Who would you rather be, landlord or peasant? If landlord, then buy a share of the freehold on offer today.

But buyer beware: this may be the most ambitious and risky plan since Icarus wanted a better look at the sun.

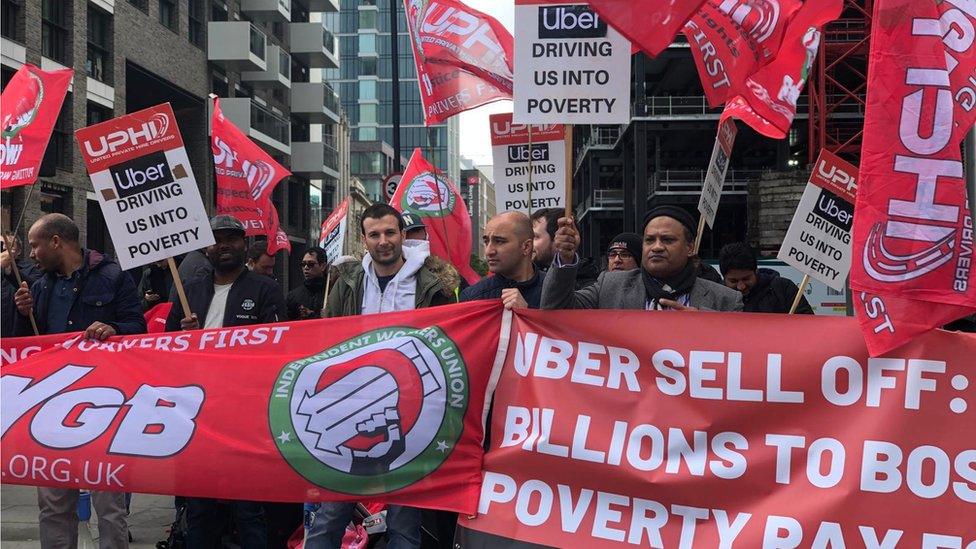

Striking Uber drivers marched through London on Wednesday

In many countries, there is already something of a "peasants' revolt" under way. Drivers in cities across the US and UK have recently gone on strike to complain about pay and conditions.

It should probably be called a protest rather than a strike, because Uber insists the drivers work for themselves. That status is absolutely key to Uber's business plan and is under legal challenge in courts around the world.

But perhaps the greatest risk to Uber is that it succeeds in its plan for world domination, only to be broken up one day. There is a growing number of voices in Europe and the US calling for an end to what they see as the suffocating domination of tech giants such as Google, Amazon and Facebook.

It seems unlikely that governments, regulators and citizens around the world will be comfortable with one or even a couple of companies dominating and monitoring the movement of all people and goods around the world.

My own hunch (neck uncomfortably out) is that there will be plenty of appetite for today's sale. Blockbuster market debuts like this don't come along very often: the last big one in the US was Facebook.

Fomo (Fear of missing out) is a powerful emotion which may overwhelm the uncertainty as to whether Uber will ever make a profit.

- Published10 May 2019

- Published9 May 2019

- Published26 April 2019