How damaging is the Huawei row for the US and China?

- Published

Rising US-China tensions have dashed hopes of an imminent trade deal

The US is ramping up a conflict with China, putting their economies and their diplomatic relationship at risk.

It has moved to restrict Huawei's ability to trade with US firms, shortly after reigniting the trade war with tariff hikes.

The latest blows to the Chinese telecoms giant mark a grave escalation in the US-China power struggle.

As the trade war broadens into a "technology cold war", the prospect of a deal looks increasingly distant.

"The US action against Huawei is a watershed moment and a very significant escalation of tensions," says Michael Hirson, Asia director at the Eurasia Group.

"A trade deal is not doomed but looks very unlikely, especially in the near term."

The crackdown on Huawei has become a central part of relations between Washington and Beijing, which has primarily played out as a trade war over the past year.

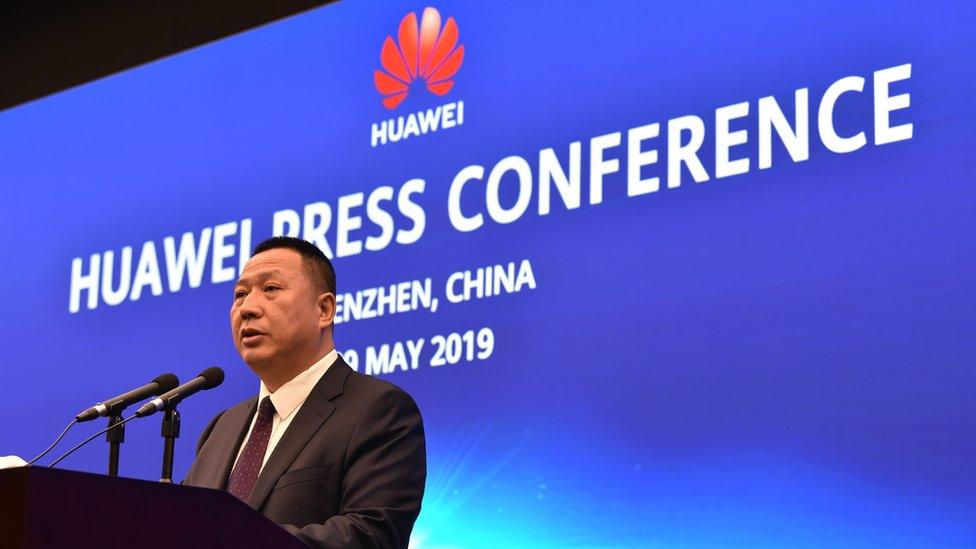

Huawei's Song Liuping says more than three billion customers could be affected

While the US has justified its actions against Huawei based on the alleged risk it poses to national security, US President Donald Trump has also linked it to the trade row.

Only recently, Mr Trump said Huawei could be part of a trade deal between the world's two largest economies.

Such comments risk reinforcing a view that the action against Huawei is about more than just security risks.

Some see it as an attempt by the US to contain a powerful Chinese firm, and by extension China's growing importance in the world.

"The prospect of a US action hobbling one of China's most prominent tech companies, and key to its global ambitions in 5G, is already evoking a surge of nationalist sentiment in China," says Mr Hirson.

How damaging are the moves against Huawei?

The US has added Huawei to a list of companies that US firms cannot trade with unless they have a licence.

Huawei has become a central part of the US-China trade dispute over recent months

At the same time, Mr Trump signed an executive order which effectively bars US firms from using foreign telecoms firms believed to pose national security risks.

"Of the two moves that Trump made - the executive order and adding Huawei to the entity list - the latter is far more impactful," says Mr Hirson.

Huawei is the world's second biggest smartphone maker and a key player in the development of next-generation 5G technology.

Its chief legal officer Song Liuping has said that more than three billion consumers could be hit by the US decision to add Huawei to the entity list.

The US moves are already sending ripples across the technology sector.

Google barred Huawei from some updates to the Android operating system. New designs of Huawei smartphones are set to lose access to some Google apps.

"If Huawei phones are undercut by the lack of Android operating system, it would hurt consumers by limiting competition in the cellphone market and causing prices to rise," says Yan Liang, associate professor of economics at Willamette University.

Analysts say the clampdown on Huawei could also hurt the development of 5G.

"Huawei also holds a dozen of patents in the 5G development. Limiting Huawei will push back 5G technology and make it more costly to implement," adds Prof Liang.

How damaging is it for US firms?

Washington's restrictions on Huawei will also hurt US firms. Huawei's Mr Song said more than 1,200 US firms would be "directly" hit.

Google is one of several firms that has stepped backed from Huawei after the US put restrictions on the Chinese company

The company's founder Ren Zhengfei recently told Bloomberg that Huawei would use more of its own chips if there were further US restrictions, and would reduce its purchases from the US.

Half of the chips Huawei uses are from US companies, and half they produce themselves, he said.

Indeed, some analysts say the US government also risks hurting itself.

"You punish Huawei but you also punish yourself: You lose market share, lose all of your business sales to Huawei," says Huiyao Wang, the president of the Centre for China and Globalization in Beijing.

"And also you probably force Huawei to develop on its own - that's not a wise move for the US."

Global Trade

What else is driving Mr Trump's confrontational strategy?

Analysts say politics is also shaping Mr Trump's approach towards China ahead of US elections next year.

There is a growing consensus in Washington that China has played unfairly in global trade for years.

Being tough on China has therefore become an easy way of scoring political points in the run-up to the 2020 vote.

The US holds presidential elections in 2020

This could mean a trade deal will not happen for some time.

"Political considerations are front and centre in the White House and certainly impacting the course of these negotiations," says Stephen Olson, research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation.

"It's possible that the political calculation - correct or incorrect - is that pursuing and extending the trade war is playing well with his political base. That would not bode well for the future."

Mr Trump will have to balance playing hardball with the risk that his China policy may contribute to an economic slowdown, along with losses in the stock market.

So is the trade deal doomed?

Even though a recent escalation in the US-China dispute has dashed hopes for an imminent resolution, analysts say a trade deal is not yet doomed.

Critically, China has shown a willingness to negotiate and analysts expect this to continue as it tries to retain the moral high ground.

China went to Washington for trade talks even as the Trump administration raised tariffs on $200bn (£158bn) of Chinese goods and threatened duties on additional products.

Mr Trump and Mr Xi are due to attend the G20 meeting in June

"Admittedly things look pretty dire right now," says Mr Olson.

"But one scenario that would be entirely plausible is that you have a little bit of a cooling off period between these countries and after a certain period of time some phone calls get exchanged, some meetings take place and we start putting things back together again."

Mr Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping are expected to meet at the G20 summit, external in Japan next month.

The meeting represents a "critical window to de-escalate tensions," says Eurasia Group's Mr Hirson.

"If the G20 passes without at least a truce, it is more likely than not that Trump will follow through with a threat to impose additional tariffs on China. Then we're looking at a long, hot summer of escalation by both sides."

- Published16 May 2019

- Published16 January 2020

- Published20 May 2019

- Published25 May 2019

- Published10 May 2019