Greek debt crisis: 'I wasn't paid for two years'

- Published

Greek entrepreneurs Dimitris Kokkinakis and Sophie Lamprou say they are unsure of the future, but will continue with their business regardless

Setting up a business in a country that is struggling to recover from a severe economic crisis is hardly the most ideal of circumstances.

So Greek entrepreneurs Dimitris Kokkinakis and Sophie Lamprou faced an uphill struggle when they set up their business in 2013.

Greece was beginning the long trek back from its debt crisis, which at one point looked like it might force the country out of the eurozone. It had imposed drastic austerity measures in response to bailouts starting in 2010.

Then in 2015, the government announced capital controls, meaning the amount of money people could withdraw from banks was restricted.

"It was a very big shock, not just for us, but for everybody in Greece," says Sophie.

Both entrepreneurs went without pay, while still paying their employees.

"For two years I wasn't paid," Dimitris says. "As soon as capital controls started, the whole economy was frozen. Everybody was saying to us, 'You need to stop', but for us it was not an option."

Dimitris, who is now 32, was forced to go back and live with his parents. Any money the organisation brought in was put back into the business.

"For young people to be independent and then have the boomerang effect... You go back to your base in survival mode," he says.

Psyrri used to have a bad reputation, but is now a fashionable area

As voters go to the polls in Greece on Sunday for the first national election since the end of the country's international financial bailout, Dimitris and Sophie said their business is facing yet more uncertainty.

Greece's ruling Syriza party is facing a major challenge after a setback in the recent poll for the European Parliament.

Dimitris says adapting to change is something they have become used to: "We need to be stubborn, and deal with complexity.

"Things can change - politically they are fluid, not only in Greece, but in the EU."

Dimitris and Sophie's business, Impact Hub Athens, is a workspace for socially-conscious organisations in the Greek capital.

They set up in 2013 in an old abandoned building in Psyrri, an area which once had a bad reputation, but is now fashionable.

The business grew organically, and now provides workspace for organisations include Ecocity, a volunteer organisation with environmental aims, and Liminal, which specialises in theatre accessibility.

To deal with political and economic uncertainty the two founders have concentrated on diversifying their clients and building resilience into the business.

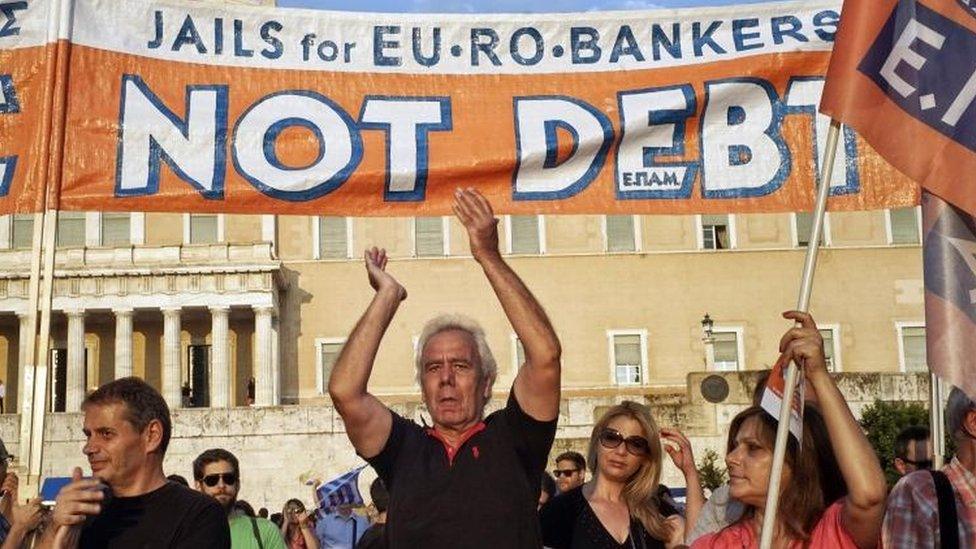

The austerity measures brought in after the bailouts led to many protests

While the economic situation has stabilised since the height of the debt crisis, Greece still faces a long haul to repair the economic damage.

The first of three bailouts was agreed in 2010 as fears grew in financial markets that the government would default on its debts.

The previous year a new government had taken office and found that the deficit in the public finances - the amount by which spending exceeded taxes and other revenue - was much larger than the previous administration had said.

There was a deep recession and two further bailouts. Greece received loans from the eurozone and the International Monetary Fund totalling €288.7bn.

Debt hangover

The money came with conditions. Greece had to undertake reforms and make deep cuts in government spending.

It was very unpopular in Greece and many economists argued that the austerity aggravated the economic downturn.

The final bailout came to a formal end about a year ago - in the sense that the payments to Greece have stopped.

But the repayments will take decades. The final one, on the current schedule, is due in August 2060.

Greek voters go to the polls on Sunday

Economic activity in Greece is still only three quarters of its 2007 peak before the crisis.

The labour market also stands out as the EU's most troubled. Unemployment is the highest at 18% and among young people it is 40%. The percentage of the working age population who have jobs is the EU's lowest.

Green shoots?

But the country has started to pick itself up.

While unemployment is still bad, it is below its peak of close to 28%, (60% among young people) and the economy has grown 5% from its low point.

The annual deficit in the government finances is far down from the 2009 peak.

The winner of the election will have their work cut out getting Greece back on its feet

The cost of servicing the mountain of Greek debt could be a lot worse, as the interest rates on loans from governments are low.

Greece has now returned to the financial markets to meet its further borrowing needs, and the costs it faces there are also modest compared with those faced at the height of the debt crisis.

However, whoever emerges as winner from the election will have their work cut out getting Greece properly back on its feet.

Sophie Lamprou says work will continue on Impact Hub no matter what happens.

"Our business is showing positive signs," she says. "Of course, in the Greek economic and political environment, you can never be very sure about what the future will be."

However, she adds: "Of course we are positive. If not, we wouldn't insist on continuing in what we do, being conscious that we are in an environment that can't give guarantees."

- Published1 July 2019

- Published13 March 2019