France tech tax: What's being done to make internet giants pay more?

- Published

France is to become the first country in Europe to introduce a tax on tech giants like Facebook, Amazon and Google. The move has upset the US.

So how does it work, what are other countries doing and what could the impact be on these huge companies?

What is the new digital tax?

The French government has approved a 3% tax on large tech companies' local revenues. This is their total sales in France, rather than the profits they make.

It will apply to tech companies with global sales of over £674m (€750m), and which make more than £22.5m (€25m) a year in France. The government argues they pay little or no tax in France.

The tax will target tech firms that put other companies in touch with customers (like Amazon), digital advertising, and the sale of data for advertising purposes.

The law will be backdated to 1 January 2019.

What will this mean for tech companies?

French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire has said that about 30, mostly US-based companies, will be hit with the new tax.

Bruno Le Maire with fellow French finance leader Christine Lagarde

It's thought it will apply to just one French company, advertising firm Criteo, as well as some Indian, British and Chinese firms.

The new tax is expected to raise £360m (€400m) for the French government in 2019, after which it could grow.

Some have argued that it could go even further, given tech companies' huge incomes.

Jessie Gaston, a Paris-based tax lawyer, said the French tax is more of a "symbol" than an effective tax measure. She said the amount it will raise for the French government is below what they'd like from the digital economy.

The move has not been well received in the US, where many of the companies are based, with claims they are being unfairly targeted.

President Donald Trump has ordered an investigation into the tax - which could result in retaliatory tariffs.

Where do tech giants pay tax at the minute?

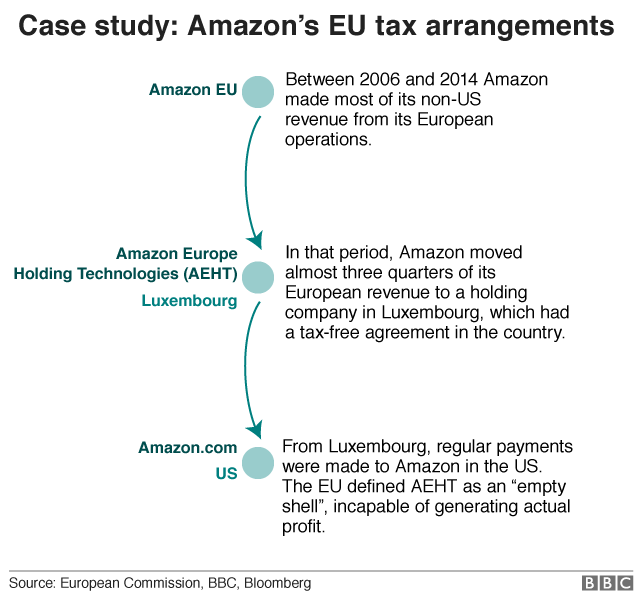

Global tech companies have been accused of finding ways to avoid tax. It is said they do this by paying most of their taxes in the EU countries where they have headquarters, rather than where they make their sales.

Often, they have offices in countries like Ireland or Luxembourg, where there are very low tax rates.

It can mean the firms end up paying very little tax in countries such as France or the UK, despite having lots of customers there.

For example, Amazon UK's 2017 tax bill totalled £1.7m, or less than 0.1% of its £2bn turnover.

But big US tech companies, including Amazon, have consistently argued they are paying all the tax they are required to under law.

What do people think of the French tax?

Following the gilets jaunes ("yellow vests") anti-government protests, French President Emmanuel Macron said businesses must pay their fair share of tax.

Protests included a blockade at an Amazon warehouse in the southern town of Montélimar, on Black Friday last November.

But critics have warned that the new tax could undermine the government's efforts to create a "start-up nation".

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo oversaw a former railway station being converted into the world's largest incubator for tech companies.

Foreign visas for tech entrepreneurs have been overhauled to make it easier to work there.

The largest incubator in the world for tech start-ups

Some economists have also suggested that the new tax could be hard to collect.

That's because it's meant to apply to income generated from French customers. But, that data isn't stored anywhere centrally.

What are other countries doing?

The United Kingdom, Spain and Italy are all looking at introducing their own versions of a digital tax.

In the UK, digital companies will be taxed 2% of their revenues, from April 2020. It will apply to companies with revenues of £500m worldwide and is expected to raise about £400m a year.

Philip Hammond and treasury secretary Liz Truss ahead of the 2018 Budget, in which the UK's digital tax was announced

The question of taxing digital companies has been an issue in the UK for some time.

In 2018, the UK retail sector lost around 70,000 jobs and saw companies like Debenhams and M&S announce plans to shut hundreds of shops. Increasing internet sales were a major factor, according to the Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee, external.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn recently sent Amazon a birthday card wishing it "many happy tax returns" on its 25th birthday.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Earlier this year, the European Commission also outlined proposals for a 3% tax on the revenues of large internet companies, with global revenues above €750m (£675m) a year.

But, critics fear an EU-wide tax could breach international rules on equal treatment for companies around the world.

And EU tax reforms need the backing of all member states to become law.

Japan, Singapore and India are reportedly planning similar schemes of their own.

Any tax measures introduced by individual countries will stay in place until a global agreement is reached.

The Organisation of Economic Development and Co-operation (OECD), an international economic organisation, is hoping to come up with a solution by the end of 2019.

- Published5 July 2019

- Published9 July 2019

- Published9 July 2019