General election 2019: How much tax do British people pay?

- Published

In the early stages of the general election campaign, the political parties have been clashing on tax.

Their plans matter because tax underpins everything the government does. The money raised is spent on everything from schools to the NHS.

So where does the UK get most of its money? And how does it compare with other countries?

How much tax are people paying?

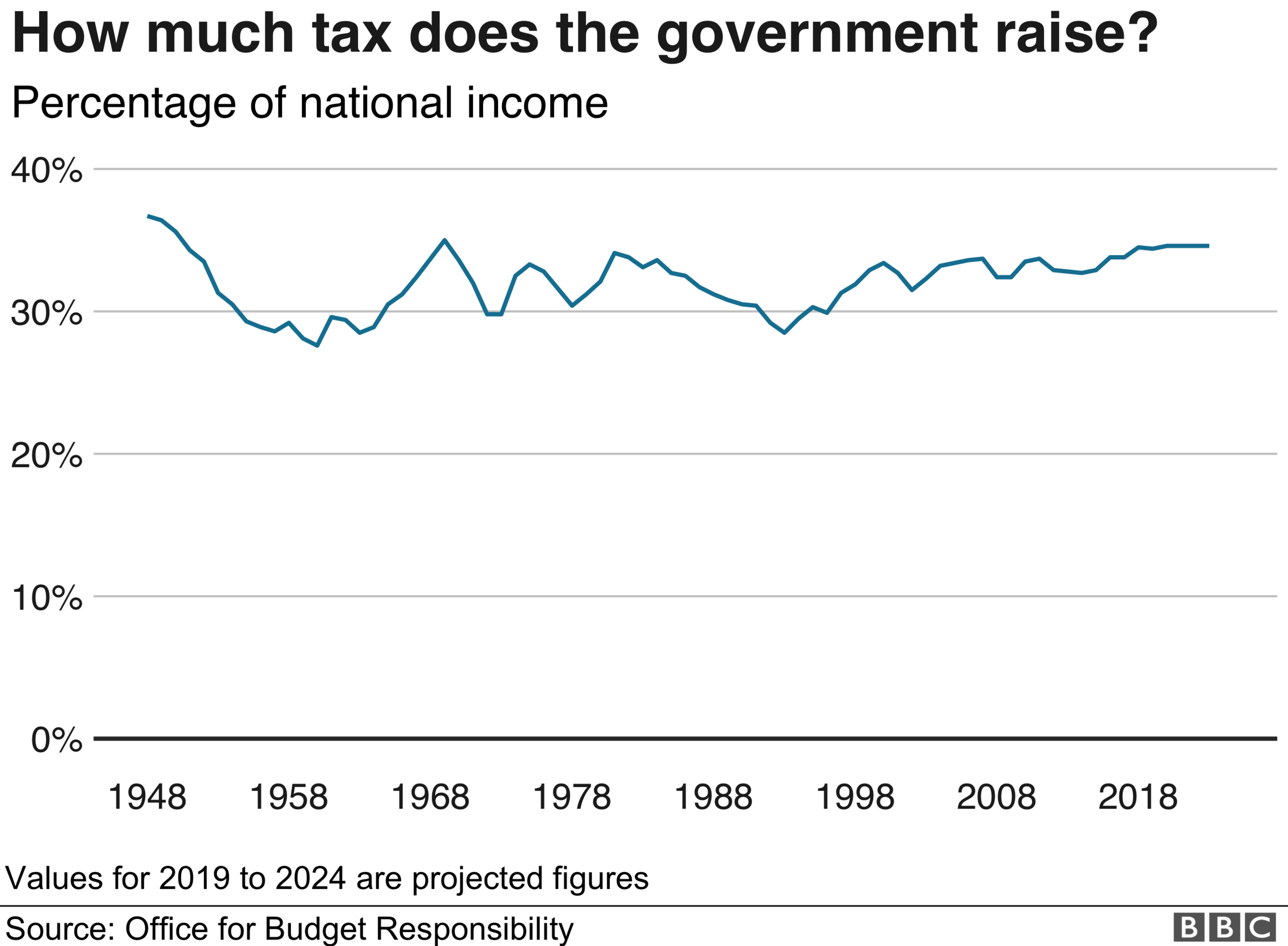

The amount of money the UK government collects through taxes is at a historical high.

UK tax revenues as a share of national income - the total amount of money the country earns - are at their highest sustained level since the 1940s.

The taxes that many of us are most aware of are income tax and National Insurance contributions (NICs).

These are the sums of money on a payslip that never reach our bank account, along with pension contributions or student loan repayments.

Together, they account for the majority of revenue collected in the UK.

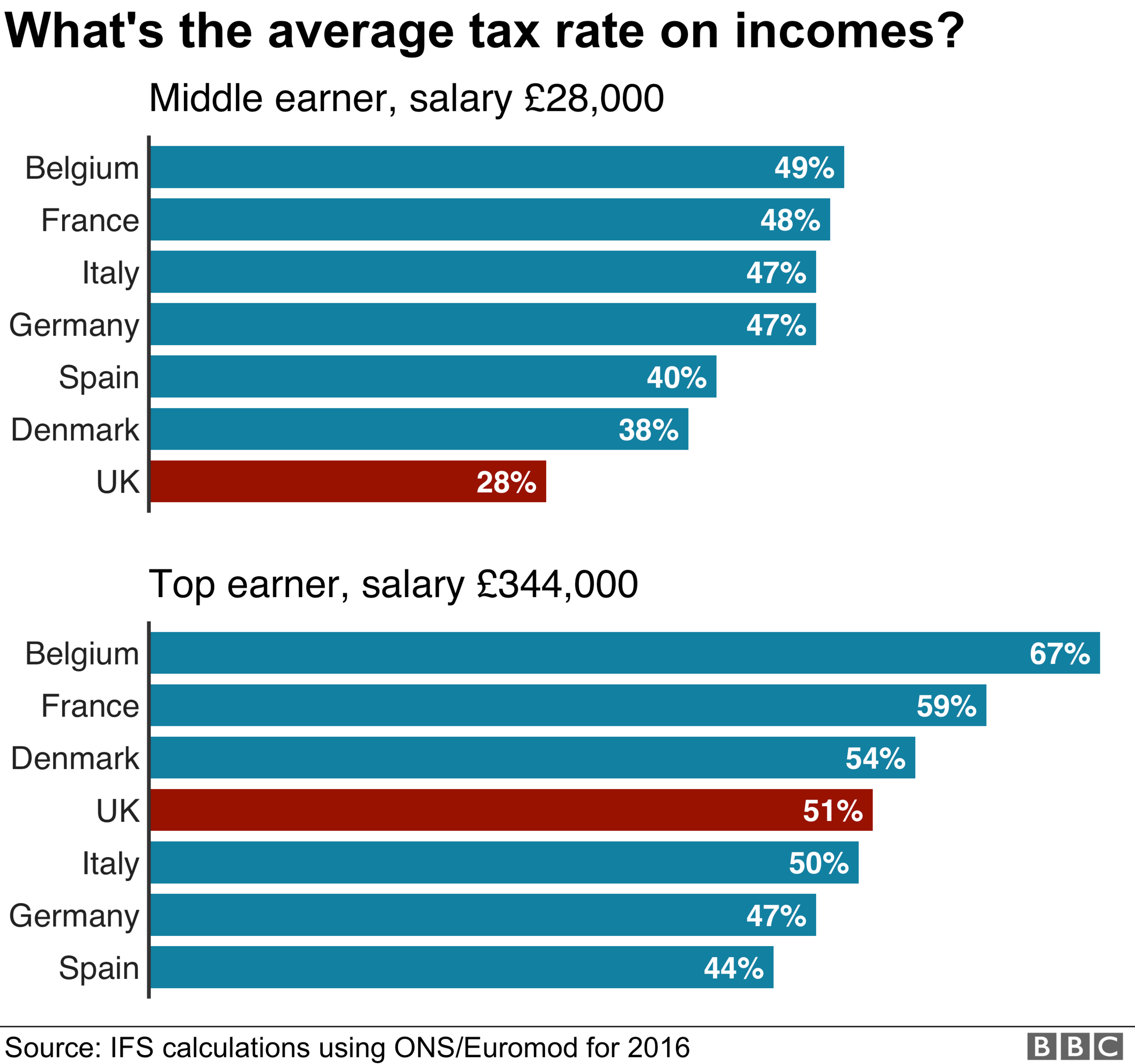

How much tax is deducted from your income depends on how much you earn. Those on higher salaries pay a higher share of their income in tax.

An employee earning £28,000 - a middle income earner in the UK - will pay nearly £6,000 in income tax and NICs. On top of this, their employer has to pay nearly £3,000 in employer NICs.

Overall, that means that about 28% of the cost of employing them ends up in the hands of the government.

Half of the cost of employing someone on £340,000 - 10 times higher than the average full-time UK employee - goes on tax.

What's it like in other countries?

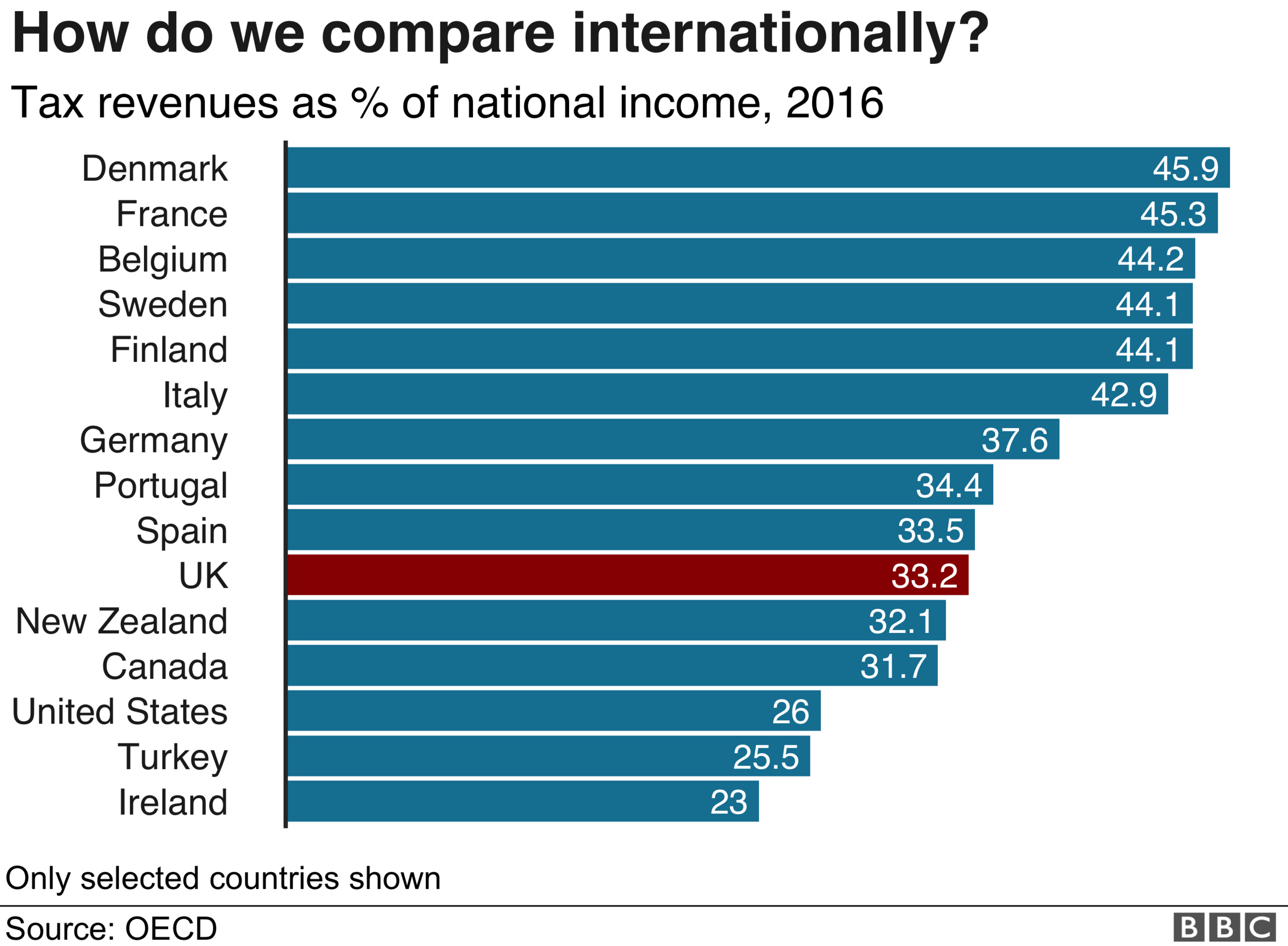

The UK is in the middle of the pack when it comes to how much tax it raises overall.

But many other European countries have much higher taxes on workers' salaries.

For example, if the UK imported the French tax system, not 28% but 48% of the cost of employing someone on £28,000 would be paid in tax. That's a big difference - £10,000 extra for the government.

The average rate for the higher earner would increase from 51% to 67% if the UK imported the Belgian tax system. That would be an extra £91,000 in tax revenue per person.

The countries that raise more in tax than the UK almost all do this by raising more from income tax and social security contributions.

Compared with European countries, the UK stands out most in its relatively light taxation of middle earners' incomes. Rates for high earners are closer to those seen elsewhere.

If the UK imported the tax system of another European country that raises more tax, average rates would increase for high earners but middle earners would be the most affected.

What other taxes does the government collect?

The amount the UK raises from other taxes is similar to that of other developed countries.

For example, VAT - the 20% tax charged when we buy many goods and services - is close to levels seen elsewhere. The same goes for corporation tax - the 19% charged on businesses' profits.

Income tax, social security contributions and VAT between them bring in most revenue in all developed countries.

They typically account for more than 70% of total government income from taxes.

But similarities in the amounts raised by certain taxes can mask important differences in who is paying them.

In the UK, zero VAT is charged on many items, including food and children's clothes.

Together, zero and reduced rates of VAT cost the government £57bn each year.

This approach is intended to help those on lower incomes. However, because richer households spend most on these items, they benefit more.

An alternative approach could be to apply the full 20% VAT rate to a wider range of goods, to raise more money. This could be used to fund benefits or income tax cuts for those who are less well-off.

Careful choices

Whether the UK chooses to have higher or lower taxes matters for the level and quality of public services the government provides.

There is a lot to think about in the run-up to a general election.

For example, pressures will continue to grow on the NHS, largely because of our ageing population. That will make health and social care more expensive.

It is likely that we will need higher taxes in future if we want to maintain the quality of public services. But how we raise tax can be just as important as how much we raise.

Whatever choices we make, we need to keep one important thing in mind - who's paying?

Find out more

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Helen Miller is a deputy director, external at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and its head of tax.

The IFS describes itself as an independent research institute that aims to inform public debate on economics. More details about its work and its funding, external can be found here.

Edited by Lora Jones

- Published1 October 2019

- Published1 July 2019