Car parts from weeds: The future of green motoring?

- Published

Weeds can be used to make bioplastics for car parts

Cars are responsible for a lot of the carbon emissions that contribute to global warming, but so is their manufacture. Could plastic made from weeds, modular designs and other innovations help the motor industry reduce its carbon footprint?

Everyone knows that driving fossil fuel-guzzling cars is bad for the environment but we often hear less about what can be done to reduce the CO2 emissions of vehicles before they even hit the road.

The carbon footprint of making a new car varies greatly depending on the model, but it is usually big. Some have calculated that as much carbon is emitted to manufacture a car as is emitted by driving it across its lifetime, external.

That's why Selena, a research group in Poland, is turning to plants that are not used in the human food chain as a potential source of eco-friendly plastics. It's called the Biomotive project and it has been awarded €15m (£13.5m) from the EU.

Car dashboards and other interior components could soon be made from bioplastics, explains Wojciech Komala, research and development director.

Wojciech Komala believes organic materials could help reduce carbon emissions

"We lower the carbon footprint by using bio-based sources," he says. "And by trying to develop lighter components for the cars."

Plant chemicals are used to synthesise polymers in the lab - a natural process harnessed for industrial use. The bioplastics that result can be heated and injected into a mould or 3D printed like any conventional plastic.

Although currently an expensive option, it is theoretically greener than using oil since plants are renewable carbon sinks - that is they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The Biomotive project will try to find out if Selena's bioplastics process can be made commercially viable for the car industry. Mr Komala says his team hopes to construct a small production factory next year.

The motor industry has done quite a lot already to reduce emissions. In the last 10 years, the carbon emissions associated with car production in Europe have fallen by nearly 24%, external, even though the number of cars produced has increased by more than 40%.

But there is still much more it could do.

One option is to make cars out of lighter materials, meaning they emit a lower volume of greenhouse gases when driven. Aluminium, say, instead of cast iron. All well and good, but it turns out that aluminium is an energy-intensive metal to mine and produce.

The production of an aluminium cylinder block consumes 1.8 to 3.7 times more energy than the production of cast iron, Cranfield University's Prof Mark Jolly has calculated, external.

It means that cars would have to be driven far longer to reap the benefits of reduced CO2 emissions on the road. In fact, in many cases they'd have to be driven for longer than their life expectancy would allow.

"The great majority of cars aren't helping - they're just increasing CO2 emissions," writes Prof Jolly.

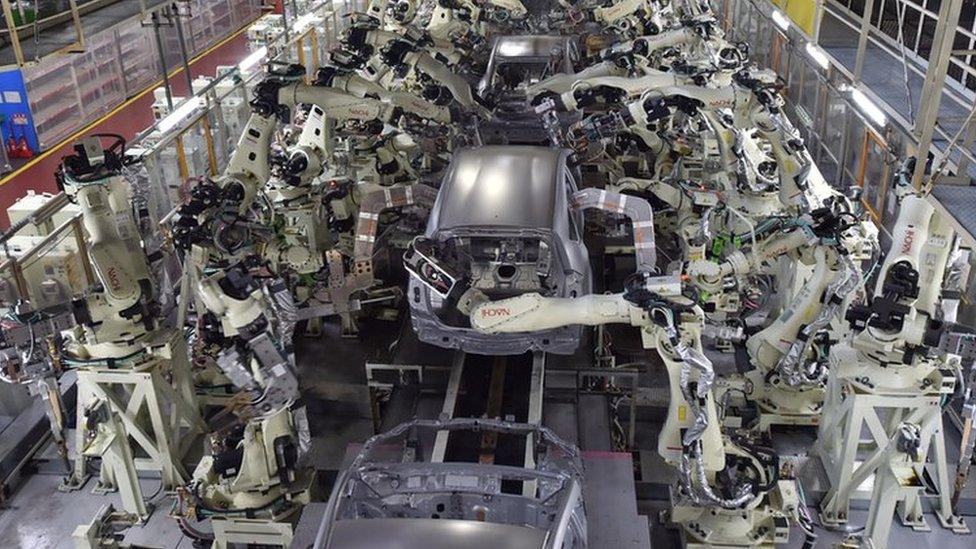

Car production is a lot more efficient these days, but still a huge consumer of energy

What about electric cars?

In principle, they are much better for the environment. But if the factory making lithium batteries is powered wholly by fossil-fuel energy then the carbon emissions of manufacturing such a vehicle could be nearly 75% higher than for a conventional car, external.

Car firms certainly want to be seen to be taking action on environmental issues.

Ford recently announced it would start using carpets made from recycled plastic bottles in a new line of Sports Utility Vehicles (SUVs). The company recycles 1.2 billion plastic bottles globally every year.

Many other manufacturers, including BMW, have switched to recycled plastics for their vehicle interiors lately.

Ford is using recycled plastic from drinks bottles to make carpets in some of its models

But is this just window-dressing?

Prof Steve Evans at the University of Cambridge's Institute for Manufacturing says the number one thing firms can do to decrease the environmental impact, per vehicle produced, is to lower the energy sucked up by car factories.

"Toyota in Europe …managed to reduce that energy per car by about 8% per year for 14 years," he says. "To me, that's the benchmark - that is amazing."

Factories, he explains, can continuously optimise equipment so that less energy is wasted overall. Thousands of tiny tweaks can add up to big energy savings.

For example, nozzles on air hoses wear over time, causing them to be less efficient. Just replacing them regularly can save energy. And back-up systems can be switched off if better maintenance means that a primary system rarely fails.

Toyota has successfully reduced energy consumption at its automated car plants

The other, more radical, idea is to rethink cars as products.

Modular cars, with identical frames that can be adapted to various models, have been touted for decades - many current models share chassis and other components.

But what if updating your car didn't mean buying an entirely new one but taking it back to the manufacturer for a serious refit?

"You could imagine a very different world," says Prof Peter Wells at Cardiff University. "You keep ownership of that car, it comes back and gets refreshed maybe on a two- or four-year cycle."

Such a service could be offered at smaller, locally based "microfactories" - a concept Prof Wells and his colleague Paul Nieuwenhuis have been researching for 20 years.

For now though, we still build cars the old-fashioned way. And, by and large, with an old-fashioned, negative impact on the environment.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external