When most people never see a £50 note, why have it?

- Published

- comments

When was the last time you saw a £50 note? Dinner with a wealthy relative visiting the UK, or tucked into a child's birthday card perhaps?

While we may rarely see such currency, there are a surprising number in general circulation.

According to the Bank of England's latest statistics, external, a total of 344 million of them, with a combined value of £17.2bn, are in the system.

While this makes them the least used notes in transactions, it means they are only slightly less common than £5 notes. There are 396 million £5 notes in circulation.

Those who use cash machines will know that neither note pops out of the slot with regularity.

Both the fiver and the £50 are hoarded, but by whom, and why has the Bank of England just announced plans to give the latter a makeover?

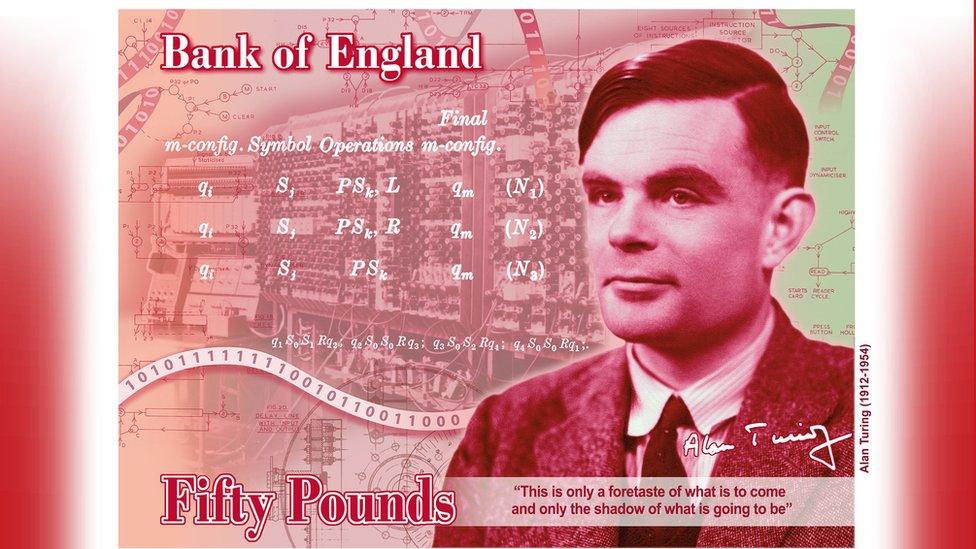

The new Alan Turing £50 will enter circulation by the end of 2021

High-value notes were once described by a former bank executive as the "currency of corrupt elites, of crime of all sorts and of tax evasion".

Peter Sands, former chief executive of Standard Chartered bank, produced a report for the Harvard Kennedy School, external in early 2016 urging the world's largest economies to do something about it.

"They play little role in the functioning of the legitimate economy, yet a crucial role in the underground economy," he said. "The irony is that they are provided to criminals by the state."

Banning the notes would not stop crime, but it would make hiding transactions more costly and more difficult, Mr Sands said.

The European Central Bank (ECB) said that, as of earlier this year, banks across the eurozone would no longer issue €500 (£450) notes.

Consumers can still spend and save them, and existing notes will still be used in the system, but there have been clear concerns over their use by organised criminals.

At one point, the Serious Organised Crime Agency - which has since been replaced by the National Crime Agency - said that 90% of the notes sold in the UK were in the hands of organised crime, leaving only 10% for legitimate tourists and business travellers.

Financial crime investigators concluded that there was no credible or legitimate use for the note in Britain, so the UK asked banks to stop handling these notes in 2010.

Regarding its own currency, in recent years there have been doubts that the £50 note would continue to exist in the UK too.

The matter was raised in a a government review last year, but it was somewhat overshadowed by questions about the future of 1p and 2p coins.

Its conclusion, following a public consultation, was that the £50 note and coppers should all remain, and that the mix of notes and coins in circulation should be unchanged "for years to come".

Rather than getting rid of the £50 note owing to concerns about criminality, the government and the Bank of England announced it would make the banknote more secure instead.

"The move will give people more flexibility over how they spend and manage their money, while making it harder for criminals to counterfeit the note for illegal activity," the Treasury said in October.

Future of cash

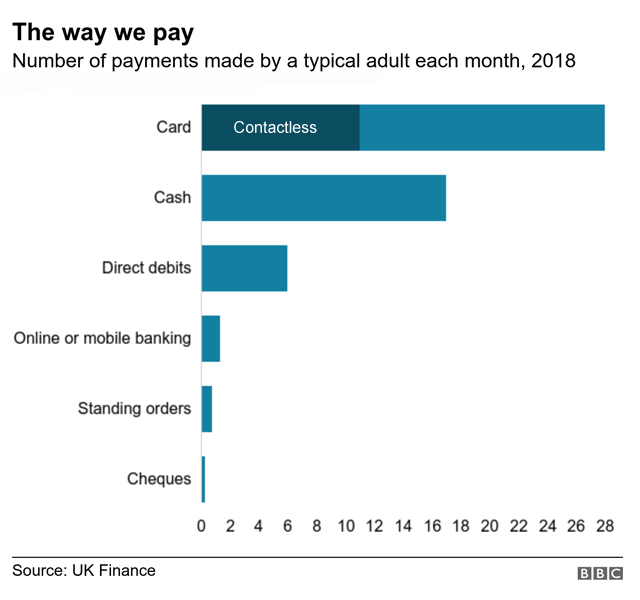

The other threat to the £50 note has come as a result not of the decisions of central banks and governments, but of consumers. They have reduced cash use, embracing contactless debit cards in its place.

However, at the launch of the Alan Turing £50 note on Monday, Bank of England governor Mark Carney said that cash, while declining in popularity, would not disappear.

"There will be demand for cash in this country for a very long period of time," he told his audience in Manchester. "This is why it makes sense to have a note like this."

A recent report into the future of notes and coins, called the Access to Cash Review, external, has proved to be influential already, prompting action from the government and regulators. It warned that the system allowing people to use cash in the UK was at risk of "falling apart" and, if allowed to do so, would seriously affect the lives of eight million people.

One of the members involved in that review, James Daley of Fairer Finance, said that while they focussed on the situation for vulnerable members of society - few of whom used £50 notes - there was a consensus on its future.

"There was a view that cash needed to be kept in all its forms," he said.

He added that it was up to the Bank of England to decide how that should happen.

We already know its plans for the short-term - a new polymer JMW Turner £20 note in 2020, and the new Alan Turing plastic £50 note by the end of 2021.

Ultimately, who uses these notes and for what reason - legitimate or otherwise - are further from its control.

- Published15 July 2019

- Published15 July 2019

- Published6 March 2019

- Published7 June 2019