Should we worry about a currency war?

- Published

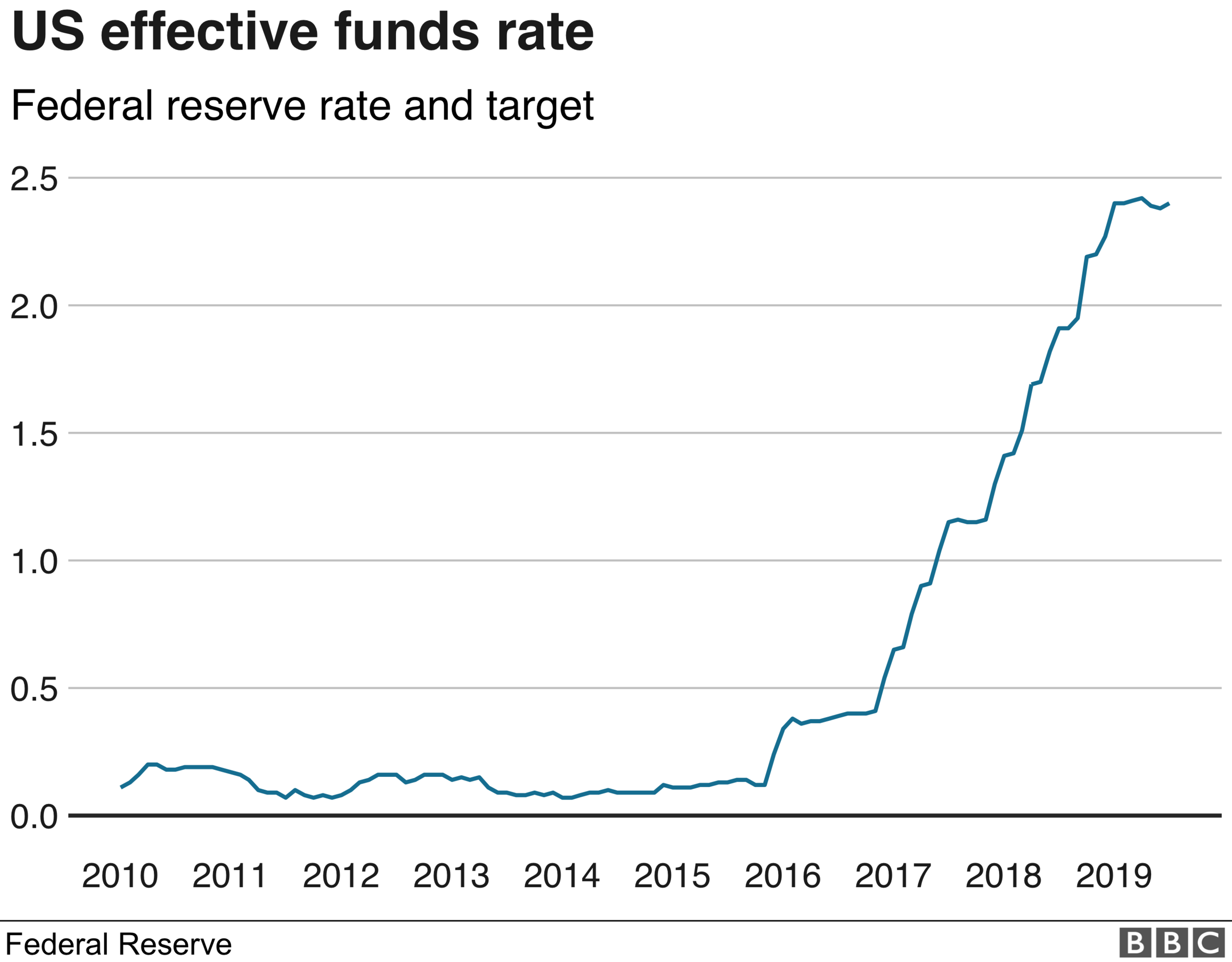

US President Donald Trump has accused the Federal Reserve of being responsible for the "very strong" dollar by keeping interest rates high.

The president tweeted that he was not "thrilled" at the result.

Mr Trump said the strong dollar made it hard for the US's "great manufacturers" to compete on a level playing field.

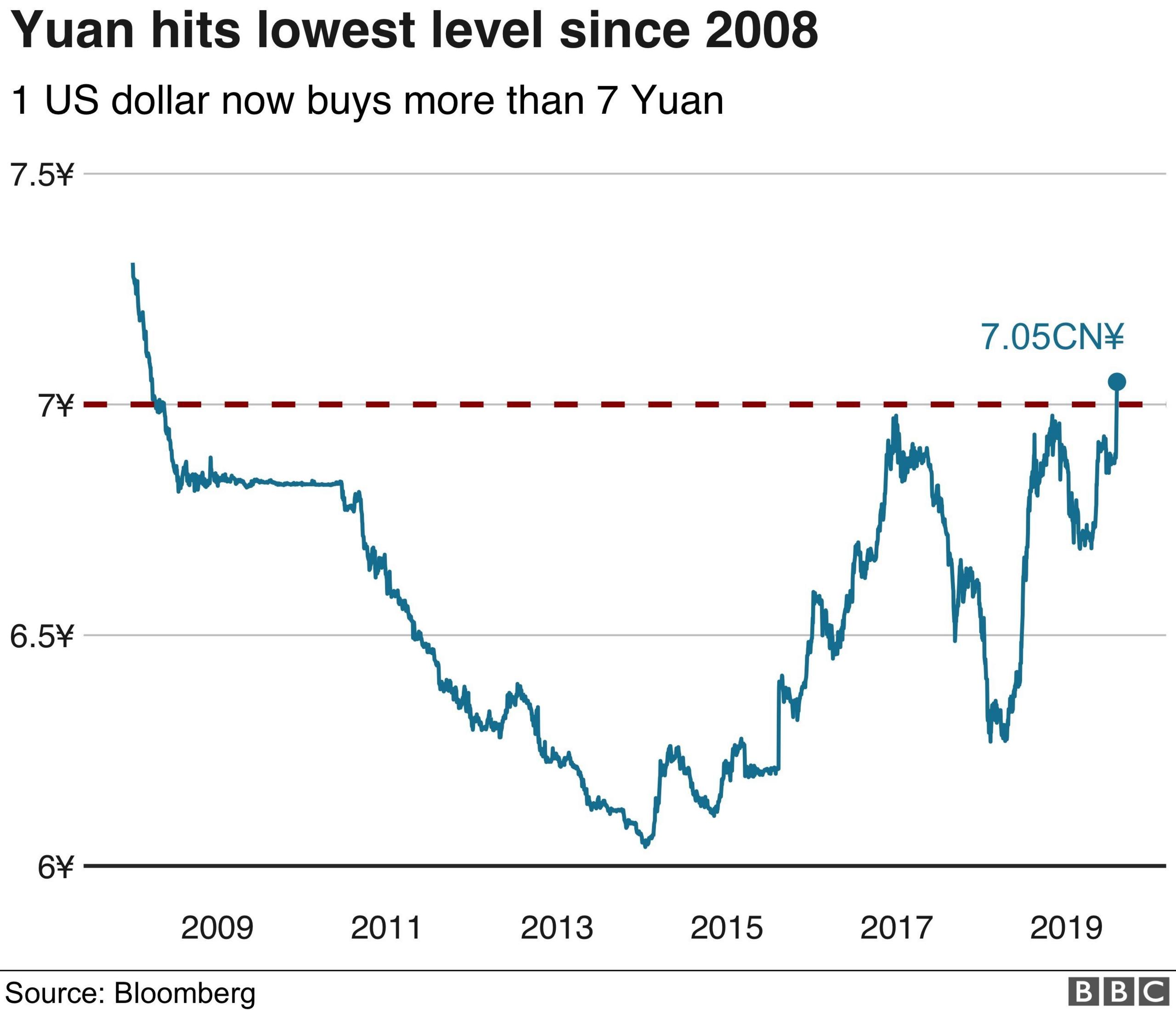

His comments come as economists fear a currency war could be sparked by China's move to let the yuan fall to its lowest level in 11 years.

Stock markets around the world have been tumbling and the price of gold - a safe investment - has hit six-year highs since China let its currency move to below seven yuan on Monday.

The shock move is seen as an escalation in the US-China trade war.

With the US describing China as a "currency manipulator", markets are trying to work out the next steps.

What is a currency war?

A currency war refers to a deliberate move by one country to engineer the price of its currency to suit its economic policy.

Some nations devalue their currency to make their exported good more competitive, boosting their overall domestic economies.

In the case of China, the authorities in the past have prevented the currency from weakening by buying large amounts of the yuan.

That policy seems to have changed this week, when China appeared to abandon that approach, which some economists said was keeping the yuan artificially high.

This isn't the first currency spat to break out. The US, for instance, last formally criticised China of being a "currency manipulator" in 1994.

More recently, in 2010, Brazil's finance minister, Guido Mantega, warned an "international currency war" was taking place when Japan, South Korea and Taiwan all tried to reduce the value of their currencies.

So is a currency war under way?

Some economists argue that a full-blown war is not under way, as neither China nor the US is formally wading into the market to buy or sell its own currency - the traditional method of moving a currency.

But Chris Turner, global head of strategy at Dutch bank ING, said that between 2015 and 2016, the Chinese authorities spent $1tn trying to stop the yuan weakening beyond seven to the dollar.

If a country buys large amounts of its own currency, it has the effect of strengthening its value on international money markets.

This week, though, such attempts were not made.

It is significant, he said, because it "comes at the height of tensions between the US and China in terms of trade".

Neil Shearing, chief economist at Capital Economist, points out that "China's currency would be reduced already, were it not for the fact that the People's Bank [of China] has been leaning against the market [until now]".

What has sparked this?

Economists see the decision to let the currency move as a weapon in the economic battle between the US and China.

It came after Donald Trump vowed to impose 10% tariffs on $300bn (£246.7bn) of Chinese imports, in the latest stage of the two countries' trade tussle.

The People's Bank of China appears to have made a direct link to the tariffs, blaming "trade protectionism measures and the imposition of tariff increases on China".

The trade war had appeared to be having an impact on Chinese trade, although data this week showed its exports started to increase again in July.

Why does the currency move matter?

It is already having a global impact, with central banks in New Zealand, India and Thailand cutting rates on Wednesday. Such a move reduces a currency: the New Zealand dollar, for instance, fell more than 2.6% on Wednesday.

Megan Greene, economist and senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, told BBC Radio 4's Today programme there was a thought that this "might be the beginning of a currency war".

"And if it is, we'll see lots of different countries trying to weaken their currencies. Of course, everyone can't weaken their currency relative to everyone else.

"The result will be an undermining of growth, higher inflation and huge volatility in foreign exchange markets."

How did Donald Trump react?

After the actions of those other three central banks, the US president again called on the US Federal Reserve to cut rates, issuing a series of tweets.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

A rate cut would not only boost the economy but, in theory at least, reduce the value of the soaring dollar.

Last month, the Fed had cut rates for the first time since 2008, with a 0.25 percentage point cut that took the federal funds target range to 2% to 2.25%.

Another way would be for the US to directly sell dollars to buy other currencies, but Ms Greene said that while the US had about $100bn of reserves which it could use to try to devalue its currency, it was not enough to make much of a difference.

"If the US is cruising for a currency war, it doesn't actually have that many tools to win one," she added.

So what happens next?

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin will now engage with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) with the intention to "eliminate" what the US describes as "the unfair competitive advantage created by China's latest actions".

Ms Greene pointed out that the IMF had previously said China was not manipulating its currency and warned it could be a "dead end".

It is making economists question what else the US might do, while the president's tweets are already leading some to expect that the US could start intervening directly.

John Normand, head of cross-asset fundamental strategy at JP Morgan, said he did not think a currency war was under way yet, since the moves in the Chinese currency this week were "private-sector driven" as international investors withdrew funds from the country.

"Before Trump, people would have assumed a currency war wouldn't happen," he said, adding that the US president "disregards all conventions".

What has happened in the past?

Agreements between the main trading nations have pledges not to manipulate currencies, although there have been agreements between nations to intervene in markets.

The 1985 Plaza Accord, for instance, was an agreement under which Japan, France, Germany, the UK and the US agreed to boost the value of the dollar.

In 2000, central banks intervened to drive the euro higher, external after the currency hit an all-time low.

And in 2011, countries jointly intervened in the currency markets to weaken the Japanese yen after it rose to its strongest level since World War Two.

Even if direct intervention in the market does not take place, Kate Phylaktis, professor of international finance at the Cass Business School, pointed out that countries can use indirect methods such as capital controls (when governments limit the flow of currencies in their countries) and monetary policy.

Leaders can also try to make public remarks that can have an impact on the value of their currencies. Such "talk" is something Mr Trump has accused the European Central Bank of, when he said in June that the fall in the euro against the dollar was "making it unfairly easier for them to compete against the USA".

Mr Shearing points to examples where sharp devaluations have eventually - although not immediately - boosted an economy, such as Argentina in 2001 and the UK after Black Wednesday in 1992 when sterling crashed out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, external.

Countries can also cause havoc when they let their currencies float freely again. In 2015, the Swiss franc soared as much as 30% in chaotic trade after the central bank abandoned the cap on the currency's value against the euro that had been in place since 2011.

- Published6 August 2019

- Published6 August 2019

- Published26 September 2022