What has gone wrong with rail franchising?

- Published

- comments

The debate over the future of running Britain's rail network flared up once more this week.

While the government tepidly defended its system, unions and passengers united to attack it as prices were hiked again above the government's own preferred measure of inflation.

Even the Department for Transport called the current model "flawed" as it announced that FirstGroup was to take over the running of the London Euston to Glasgow Central route.

The Transport Secretary, Grant Shapps, hailed the deal as a shift to a new model for rail.

But the RMT union's general secretary, Mick Cash, described it as a "another political fix by a government whose privatised franchise model is collapsing around their ears".

It all comes as rail punctuality across the country languishes at a 13-year low.

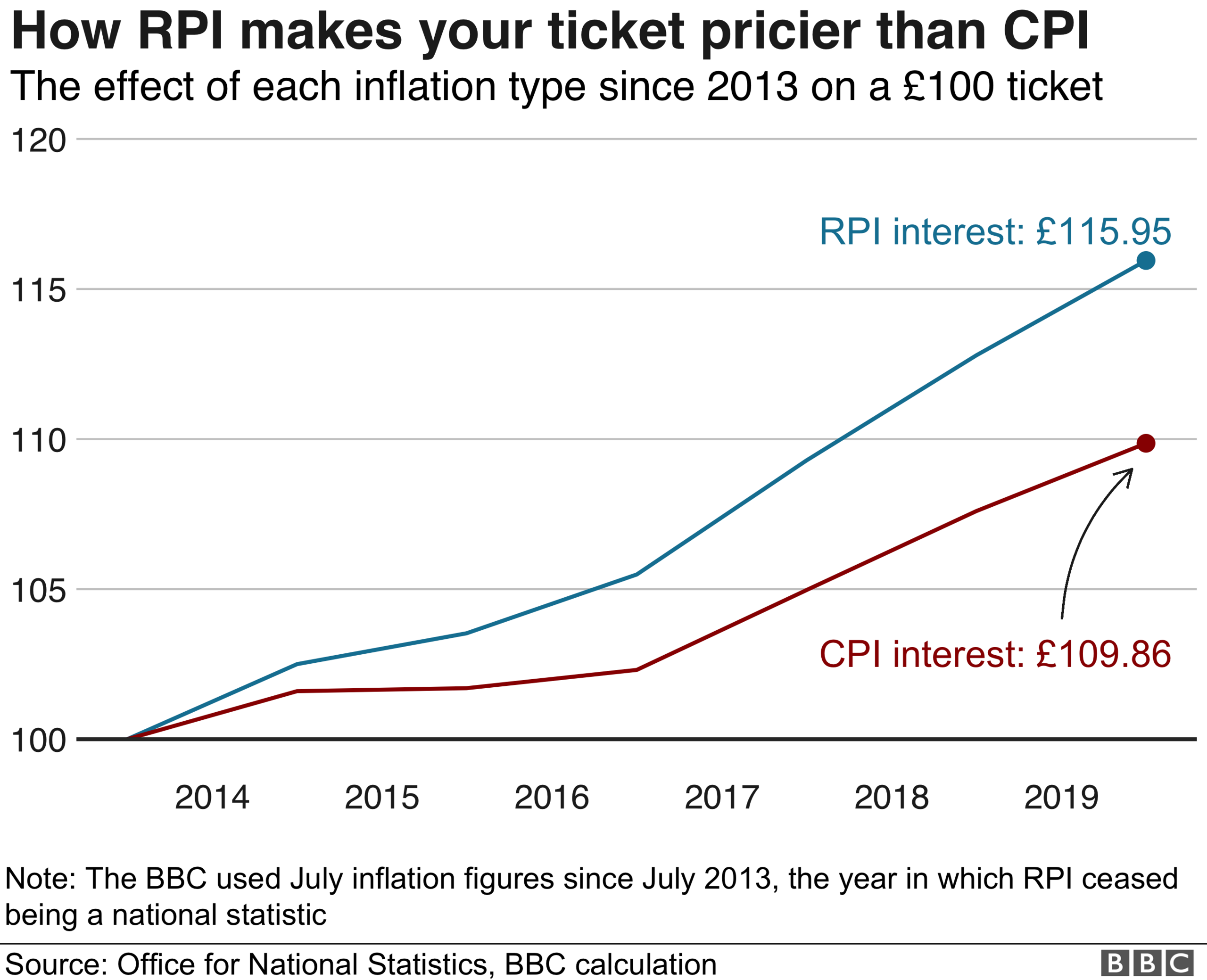

And despite growing passenger anger, fares will rise next year in line with the abandoned Retail Prices Index at 2.8%, rather than the lower Consumer Prices Index.

"The system is clearly not working, everybody agrees that it's not working," rail writer Christian Wolmar tells the BBC.

What's going wrong?

The Department for Transport maintains that privatisation has worked. It points out that passenger numbers have doubled, while the rail system has attracted £6.7bn of private investment and added 4,600 new daily services.

But the mounting criticism of the system was clearly not what the government had hoped for when it privatised the network in the 1990s.

Network Rail, then known as Railtrack, was set up to look after the tracks, tunnels and signalling. Meanwhile, private companies could compete to run the trains.

At the time, the government hoped that those private firms would compete on most routes through a system known as "open access". Rather than bidding for entire lines, services themselves were on offer.

It also asked firms to bid to run subsided franchises on loss-making routes.

But that left the taxpayer to pick up the tab for all loss-making services. When the network was publicly-owned, these would have been subsidised by the profitable ones.

As a result, franchises for entire lines became the norm to stop the cornering of profitable services, and now less than 1% of passengers travel on open-access services.

'Little control'

The effect of that has been a lack of competition among train operators which is bad for consumers, says Professor Mark Barry from Cardiff University.

"We've got a system that was meant to bring competition to railways post-privatisation and provide some means for companies to innovate, take a risk in return to procure some value.

"The reality is though, there isn't a lot of competition on the railway - apart from the franchising system itself."

This might suggest that train operators are having an easy ride and raking in profit, but the opposite is often the case.

As Mr Wolmar points out, in reality rail companies have very little control over their revenues. They can introduce wi-fi on their trains and launch advertising campaigns but much of their fortune depends on factors beyond their control, such as employment levels and economic growth.

Fares will rise by up to 2.8% next year

In a competitive tendering environment, that can mean that the rail firms make a loss over the course of rail franchise, which typically lasts seven years.

And that explains, in part, the failure of Stagecoach and Virgin Trains' East Coast Main Line franchise, which was handed back to the government last year.

Prof Barry thinks the franchising model should change so that the franchisee is not left with the revenue risk.

Instead, he argues, the government should award contracts by telling the bidders how much money is available and asking them to compete on quality.

He said Transport for Wales had experimented with that model successfully.

The man charged with reviewing the franchise system, former British Airways boss Keith Williams, may have an even more radical suggestion.

Punctuality on UK trains is at a 13 year low

He has said a "Fat Controller" type figure, independent from government, should be in charge of day-to-day operations.

Mr Williams has also said he believes that, in the future, rail franchises should be underpinned by punctuality and other performance-related targets.

The government launched the review after passengers in northern and southern England experienced chaos over several weeks last summer following the introduction of a new timetable.

His review of the rail system will be published this autumn.

A Department for Transport spokesperson said: "The recently awarded West Coast Partnership represents a decisive shift towards a new model for rail. It is a partnership supported by Keith Williams, built with the flexibility to respond to his recommendations and deliver fundamental reform to a flawed system.

"The transport secretary has asked Keith to produce his recommendations for a White Paper, with fearless proposals that will deliver a consumer focussed railway system fit for the 21st Century."

- Published16 July 2019

- Published14 August 2019

- Published16 May 2018