How business is adapting to Hong Kong's new reality

- Published

Foreign companies face a new business reality in Hong Kong. There's a rising sense of uncertainty washing over the corporate world here, as firms confront a shifting political landscape after months of unrest.

Millions of Hong Kong citizens have taken part in pro-democracy protests that have drawn the ire of many in mainland China.

Just this past weekend, thousands of people took to the streets to mark the fifth anniversary of China's government banning full democratic elections in Hong Kong, despite police outlawing the protests.

And on Sunday, demonstrators aimed to block access to the airport by suspending transport links in the city.

Business is counting the cost of the damage these protests have inflicted on the reputation of Hong Kong as a global financial hub, but far more worrying for companies is what many say is the strong-arming by China of companies in Hong Kong.

Cathay Pacific provides the strongest example yet of how perceived missteps in Beijing's eyes can harm businesses in the territory.

Dressed in black and carrying signs, hundreds of protesters gathered at a rally last week to support staff from the airline who say they lost their jobs because they supported the protests.

No gas masks or tear gas here, just ordinary workers trying to make their voices heard.

How Hong Kong got trapped in a cycle of violence

Many at the rally told me they were worried they could lose their jobs too - simply for thinking or saying something Beijing may not like.

"It's become more like China," one woman told me. "These are tactics used by Communist governments to silence people. Like allowing colleagues to tell on each other, just because they see something that is not in favour of the government. They could report that to the authorities and get that member of staff to be fired for no other reason."

'Difficult tightrope'

It's not an unrealistic fear.

Earlier this month Cathay Pacific saw the high-profile resignation of chief executive Rupert Hogg, who said he had to take responsibility for the controversy over some of his staff joining pro-democracy protests, angering Beijing.

Protestors demonstrated against recent sackings at airline Cathay Pacific

But many speculated Mr Hogg was forced out, because that's what China wanted.

"I've never seen anything quite like this," said one prominent businessman in Hong Kong, who didn't want to be identified.

"We have to walk a difficult tightrope now," he said. "No multinational is leaving yet, I've not seen any evidence of capital outflows, but companies are going to have to tell their staff to be far more careful about what they say and what they do. The Cathay Pacific example was a warning from Beijing."

Pressure mounts

Many in this city don't see themselves as part of China. They value being distinct and separate.

One country two systems has meant the rules have always been different here, and that's what's helped Hong Kong thrive.

But the sense now is that's changing.

Many in Hong Kong's crucial financial industry are reluctant to talk about how they're reacting to the political shifts, fearful of being singled out by China.

But sometimes actions speak louder than words.

Take, for example, the full page ads in newspapers that banks like HSBC and Standard Chartered took out to condemn the violence in Hong Kong.

Analysts say for companies that make most of their revenue from China, it is now more important than ever to be seen as supportive of Beijing's position on the protests.

Transport shutdown

And there's already evidence that some businesses are bowing to pressure from Beijing.

Hong Kong's MTR Corp runs the subway system in the city. It's used by the majority of Hong Kongers and is seen as a world class transport service.

It's also the main way protesters have been making their way around the city during the weekend demonstrations.

That's led to harsh editorials, external in China's government mouthpieces the People's Daily and Global Times which have slammed MTR Corp for allowing them on board.

Subsequently the railway operator closed down stations on two of its main lines over a weekend when protests were being held, in a move that was widely seen as giving in to China's demands - which it denied.

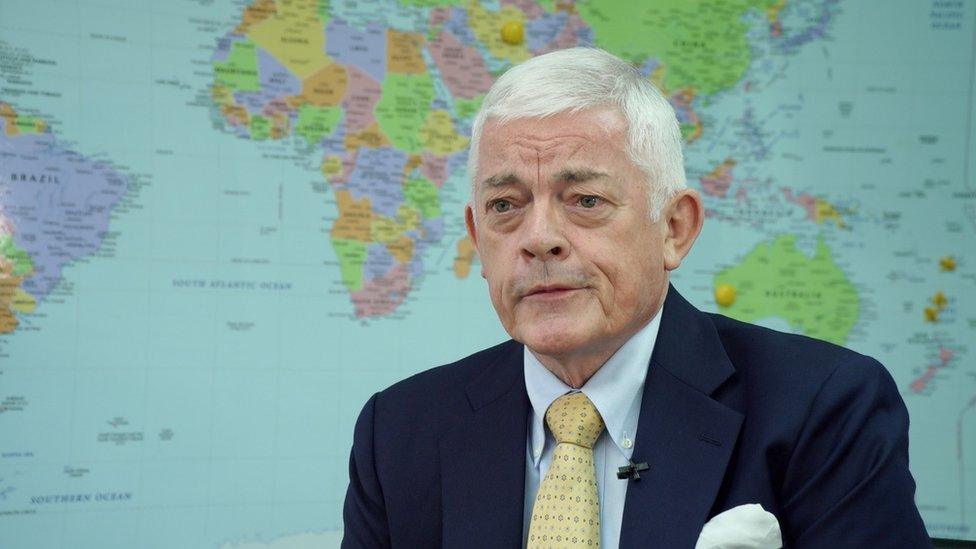

Political risk consultant Steve Vickers says that companies will have to "bend like bamboo" if they want to keep working in the region

While MTR Corp doesn't make as much money from the Chinese market as Cathay Pacific does, it does operate some lines on the mainland and saw revenues from China grow by 44% in 2018, external.

The harsh reality is that companies will have to "bend like bamboo", and do what Beijing wants if they want to keep servicing the Chinese market, says Steve Vickers who runs a political risk consultancy in Hong Kong.

Mr Vickers says in the future Hong Kong-based firms may have to employ government liaisons the way they have in China, to navigate the increasingly tricky political landscape.

"At the end of this, I think we will see further control from Beijing," he told me.

"Does toeing the line with Beijing now damage my [standing in the] global market?" he said, referring to the decision businesses based in Hong Kong have to make and the difficult position they're in - whether to side with pro-democracy protesters, or against them.

"Or do I kowtow now and protect my position on the mainland? That's the big decision that people are making."

But it's a contract that veterans in Hong Kong have always understood.

In the city's iconic entertainment district Lan Kwai Fong, I met Allan Zeman, the man who helped to build it.

Dotted with bars and restaurants, and people spilling out onto the streets enjoying the midweek revelry, you can almost forget that this is a city beset by protests.

Mr Zeman told me that doing business in China means understanding the culture, and that all Beijing wants is some 'respect.'

"I've been in China for more than 35 years, I've done business there for 35 years," he told me. "I understand it. These are the rules. If you want to do business there abide by the rules."

It sounds simple enough, but it's at the root of the conundrum now facing Hong Kong.

- Published28 November 2019

- Published13 August 2019

- Published17 August 2019