Jet fuel from thin air: Aviation's hope or hype?

- Published

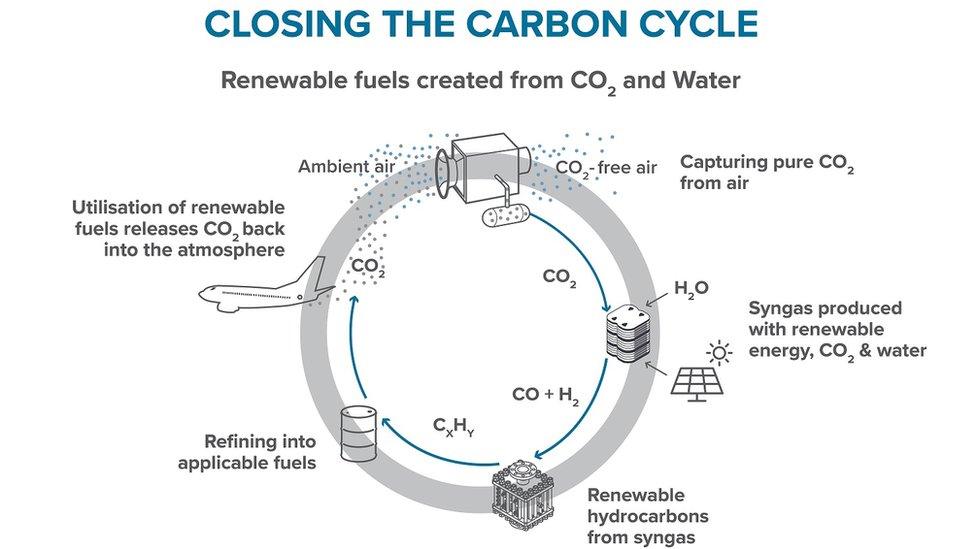

Direct air capture takes CO2 straight out of the atmosphere

"This is the future of aviation," Oskar Meijerink tells me in a café in Rotterdam airport.

His company, in partnership with the airport's owners, is planning the world's first commercial production of jet fuel made, in part, from carbon dioxide (CO2).

Based at the airport, it will work by capturing CO2, the gas which contributes to global warming, from the air.

In a separate process, co-electrolysis splits water into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen is mixed with the captured CO2 to form syngas, which can be transformed into jet fuel.

The pilot plant, which aims to produce 1,000 litres of jet fuel a day, will get its energy from solar panels.

The partners in the project hope to produce the first fuel in 2021.

They argue that their jet fuel will have a much smaller CO2 impact than regular fuel.

"The beauty of direct air capture is that the CO2 is reused again, and again, and again," says Louise Charles, from Climeworks, the company which provides the direct air capture technology.

Oskar admits that the fuel has a long way to go before it is competitive.

"The main element is the cost," Oskar Meijerink, from SkyNRG, concedes.

"Fossil jet fuel is relatively inexpensive. Capturing CO2 from the air is still a nascent technology and expensive."

Other companies are working on similar direct capture systems, including Carbon Engineering in Canada and US-based Global Thermostat.

But environmental campaigners are highly sceptical.

"It sure does sound amazing. It sounds like a solution to all of our problems - except that it's not," said Jorien de Lege from Friends of the Earth.

"If you think about it, this demonstration plant can produce a thousand litres a day based on renewable energy. That's about five minutes of flying in a Boeing 747.

"It'd be a mistake to think that we can keep flying the way that we do because we can fly on air. That's never going to happen. It's always going to be a niche."

While companies are experimenting with high tech ways to capture CO2 from the air, there's already a very simple, efficient way to do it - growing plants. And aircraft are already flying on renewable fuels made from plant biomass.

Sugar cane, grasses or palm oil, and even animal waste products - effectively anything that contains carbon - can be processed and used.

But are these alternative fuels ever going to replace traditional fossil jet fuel?

"Yes, but it's very difficult to set a time frame," says Joris Melkert, senior lecturer in aerospace engineering at Delft University of Technology.

Alternative fuels are struggling to compete with traditional jet fuel

He says that alternative fuels will become competitive, if the environmental costs are built into the cost of flying, but that will mean more expensive tickets.

"It'll highly depend on social pressure but there are no technical objections."

"Basically if you look at the ways to make transport more sustainable, aviation is the hardest to change."

Air travel accounts for between three and five percent of the global CO2 emissions and those emissions are growing fast.

Looking for options

In response, aviation's industry body (Iata) has set targets to reduce emissions by 50% by 2050 and airlines are exploring many ways to cut back on the use of fossil fuels.

The Scandinavian airline SAS aims to run domestic flights on biofuels and cut emissions by 25% within the next decade.

KLM is actually encouraging people not to fly, and suggests customers might want to take the train or hold video meetings over the internet.

And recently Dutch low-cost carrier Transavia started weighing passengers at Eindhoven airport, in an experiment designed to better calculate the amount of fuel required with the aim of reducing CO2 emissions.

Transavia will also be the first customer for the jet fuel made by the experimental operation at Rotterdam Airport.

Jorien de Lege from Friends of the Earth says we will have to cut back on flying

Some are hoping that electric or hybrid planes might be the answer.

EasyJet, in partnership with US based Wright Electric, is developing electric planes that would be able to service short-haul routes by 2030.

But Joris points out that even if the engineering problems are worked out, the average plane has a life span of 26-and-a-half years, so "we're stuck with them for decades".

He believes biofuels have the greatest chance of reducing the industry's reliance on conventional fuels.

"There's no silver bullet," Joris warns. "But renewable fuels will give the biggest steps towards reducing the environmental impact."

"At the moment it's just way too expensive. It just depends how great the pressure gets to say how fast airlines adjust."

'Tough choices'

Not everyone is persuaded these technological workarounds will be the magic wand to make flying more sustainable.

"The only solution we have is simply to be flying less," says Ms de Lege from Friends of the Earth.

"I'm very sympathetic to all the reasons why we need to fly around the world but climate change isn't [sympathetic], and it's accelerating at a rate that's terrifying.

"We need to make tough choices. We need to think about system change. I'm confident we can see our lives as very comfortable without flying, they're just different."

Follow Technology of Business editor Ben Morris on Twitter, external