Smart meters: What is going on?

- Published

Smart meters are promoted as technology to make householders' lives easier and cheaper, as well as a gateway to a connected British energy network.

But their introduction has proved controversial. Deadlines have shifted and the technology has been questioned.

Ultimately, most homes in the country will eventually use smart meters. So how do they work and how will they affect our use of energy?

What is a smart meter?

A smart meter measures energy use, in the same way as a traditional gas or electricity meter. Unlike its predecessors, it sends that information directly to an energy supplier.

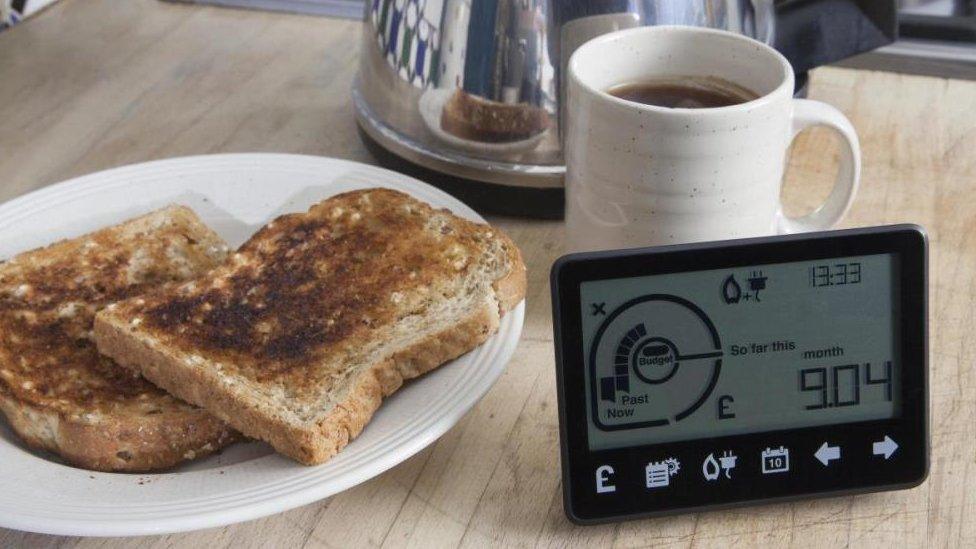

Householders can track their energy use on a display screen, which should also show them the cost of how much they have used in pounds and pence.

What are the benefits?

The big selling point for smart meters (although you do not have to buy one) is that it means an end to estimated meter readings, or residents having to read the meter themselves.

The information is sent through a wireless connection almost in real-time. As a result, every bill should be an accurate reflection of the amount of energy used.

That means the costs to suppliers should be lower and, with consumers tracking and cutting energy use at expensive times, bills could be cut.

The National Audit Office estimated that consumers would save less than £11 annually, after the cost of installation is factored in.

Prepayment meter customers could also have more automated options to top-up their credit and make sure their supply is not cut off.

The long-term promise is that residents will benefit from tailored packages that give them discounts for using energy at times of low demand, such as weekends.

It will also help suppliers to anticipate energy use, reduce waste, and make the system more efficient to tackle the effect on the environment.

What are the problems?

The first generation of smart meters do not necessarily continue working if a customer switches supplier. They still measure usage, but some will "go dumb" so residents have to start sending their meter readings again to their new supplier.

The second generation is designed to be more flexible and work through a network of multiple suppliers, but not all companies are fitting these new designs as yet.

Last year, the National Audit Office said that the coldest parts of the country were the least likely to have a smart meter installed, even though the need in such regions was greater.

Some other glitches have been leaving customers frustrated.

"My smart meter loses connection, the weather seems to affect it, and it beeps all the time and the only way to stop it is to remove the batteries," Bryde Town, from Halifax, told BBC News earlier this year.

More bizarrely, a handful in England showed displays in Welsh.

When should it be fitted?

The most controversial element of all has been the speed at which these meters have been installed in people's homes.

There was a pledge in the Conservative Party's 2017 election manifesto that every household and small business in Britain would be offered a smart meter by the end of 2020. The energy regulator, Ofgem, had a rule that the energy companies had to take "reasonable steps" to fit meters by that time.

The latest government announcement has added a target that gives suppliers until the end of 2024 to install smart meters in at least 85% of their customers' homes - in effect an extension to the smart meter roll-out.

Do I have to accept one?

Suppliers are contacting customers, offering to install a smart meter. There is no upfront cost. It is possible for customers to request one directly from their supplier.

However, it is not compulsory to have one. Householders can also choose to have one at a later date, without any charge.

Tenants who pay electricity and gas bills directly to their supplier, rather than through their landlord, can accept or request a smart meter, but Ofgem suggests they inform their landlord of the move.

- Published17 September 2019

- Published13 September 2019