‘I’m being jailed for four emails from 12 years ago’

- Published

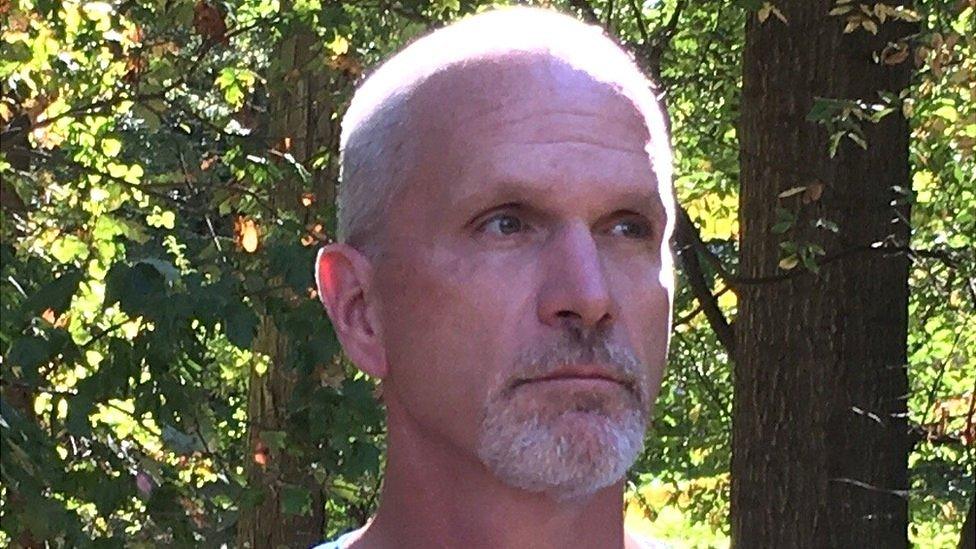

Matt Connolly says there have been miscarriages of justice

The crime for which Matt Connolly was convicted, alongside British co-defendant Gavin Black, is conspiracy to commit fraud by rigging interest rates. The documentary evidence implicating him is four emails between 12 and 14 years old.

Connolly, 54, from Basking Ridge, New Jersey, and Black, 49, from Twickenham, southwest London, are the latest in a line of 11 traders to face jail for the same offence. At their sentencing hearing later this month, the US Department of Justice (DoJ) is pressing for Connolly to get at least nine years.

By speaking out against his investigation and trial, Matt Connolly risks a longer sentence. But so shocked is he by his experience at the hands of the US justice system, he is determined to go public, publishing a book and giving an interview that could bring further time in a prison cell.

"If I have to face more jail time for getting the truth out there, so be it. Because at the moment no-one realises what's gone on and how bad it is. I can't stay silent," he told the BBC.

In common with nine other traders convicted of the same offence, the documentary evidence against Matt Connolly and Gavin Black consists of emails or messages making requests of colleagues.

The US DoJ case was that these requests showed a fraudulent scheme to try to move the benchmark interest rate that tracks the cost of borrowing cash, Libor, to make profits on their trades at the expense of others in the market.

"In their quest to make every extra dollar that they could… they cheated by rigging the Libor interest rate," said DoJ prosecutor Alison Anderson at the start of the trial.

"They did it just to make more money for their bank and in turn more money for themselves… they cheated businesses and defrauded businesses around the world, right here in the United States and right here in New York."

What the Nikkei or the FTSE 100 are to share prices, Libor is to the cost of borrowing cash: an index or benchmark, updated every day.

The real interest rates paid on millions of consumer loans and mortgages depend not on official central bank interest rates but on the real cost to the banks of getting cash to lend. Libor keeps track of that cost by showing the average interest rate banks are paying to borrow funds from each other.

Former Deutsche Bank traders Connolly and Black both face jail for taking part in an international conspiracy to "rig" Libor from 2005 to 2010.

Yet until December 2017, when they attended court in New York, Connolly and Black had neither met nor spoken. No personal email has been unearthed from one to the other and Connolly, a former desk supervisor, left Deutsche Bank in March 2008.

"This was the weird thing. We were accused of being in a criminal conspiracy. But we didn't actually know each other," Connolly said.

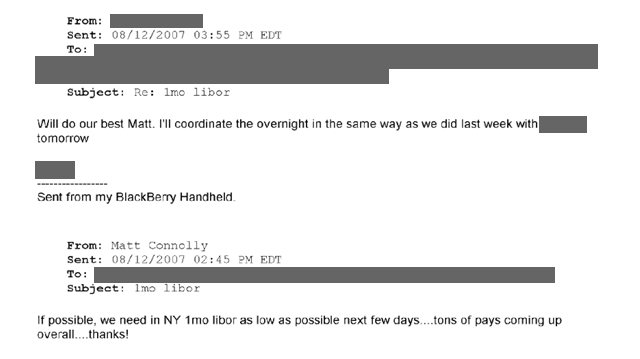

Matt Connolly wrote three emails making requests about Libor, the most recent of which dates from August 2007. He was copied in on another. At the New York court, it was enough to condemn him to jail.

On the one hand, prosecutors were unable to prove at the trial that Connolly and Black procured false statements that caused identifiable losses for others, nor to produce as a witness a victim of their actions. On the other, prosecutors did not need to show a fraud succeeded. For a charge of conspiracy, they needed only to convince the jury one was planned.

"To convict them on the charges, you need to do nothing more than accept at face value the statements they made in which the defendants and their co-conspirators requested and submitted rates… to benefit trading positions," DoJ prosecutor Carol Sipperly told the jury.

To work out Libor, a trader at each of 16 banks given the role of "Libor submitter" has to make an estimate, to at least two decimal places, of what interest rate they think their bank would have to pay to borrow cash from another bank (for example, RBS estimates 3.53%, Lloyds 3.55%). An average of those 16 estimates, or "Libor submissions", is taken and published as Libor - the London Interbank Offered Rate.

Because banks also have billions of dollars in investments, loans and trading positions linked to the Libor average, they could make or lose money if Libor moved up or down by as little as one hundredth of a percentage point. So traders who knew the banks' positions would work out which way the bank was "facing" - whether it would benefit from a higher or lower Libor rate.

The traders would then frequently make requests for the Libor submitters on the cash desk to put in "high" or "low" Libor estimates. If the submitter accepted the request, they would typically tweak their submission up or down by a hundredth of a percentage point or two - for example, from 3.53% to 3.54%.

In nine rate-rigging trials since 2015, prosecutors have interpreted those "trader requests" as criminal - an attempt to procure false Libor submissions with the goal of skewing the Libor average in their favour, at the expense of others in the market.

The DoJ and the UK's Serious Fraud Office (SFO) insist there was only one "true" or "honest" estimate of the cost of borrowing cash that a submitter could put in.

Therefore any attempt to influence it up or down to serve a bank's commercial interests must be dishonest. So when Connolly emails a colleague saying: "We would prefer it higher… thanks just asking is very much appreciated", the DoJ sees it as a criminal attempt to procure a "false or fraudulent" statement.

Prosecutor Carol Sipperly told the jury: "They would get that Libor submitter… to move the Libor submission higher or lower, not based on any honest estimate of what that Libor submitter thought Deutsche Bank would have to pay to borrow money but in whatever direction benefited the defendants and their team on their trades."

But trader requests have been viewed by other courts in a more innocent light: as requests for submissions that were adjusted to take account of the bank's commercial interests - yet were nevertheless accurate. The defence is that it was accepted practice to ask for "high" or "low" Libors - because there was a narrow range of accurate rates to choose from.

Connolly's lawyer Ken Breen pointed to the Libor definition set out by the body that owned and ran Libor, the British Bankers Association (BBA), telling each bank to "contribute the rate at which it could borrow funds, were it to do so by asking for and then accepting interbank offers" [italics added].

"Some witnesses have noted that 'offers' is plural, which is important. On any given day, there was a range of offered rates where Deutsche Bank could borrow funds. Even the prosecutors' own expert supports this point… he drew the conclusion there is a range of true borrowing costs, that's a range of true, honest, accurate rates, not just one," Mr Breen told the court.

Former Deutsche Bank Libor submitters, Mike Curtler and James King, both accepted on cross-examination that there would be more than one interest rate at which the bank might borrow cash (for example, an offer at 3.55% from UBS, another at 3.53% from Lloyds). Mr Curtler also testified that Connolly had never made a request for a Libor submission outside the range of interest rates at which the bank might realistically borrow.

However, in her closing speech DoJ prosecutor Carol Sipperly denied that a range of accurate Libor estimates existed, saying it was "made up after the fact". That echoed repeated statements in the first Libor rigging trial, of Tom Hayes in 2015, where SFO prosecutor Mukul Chawla repeatedly said a range of accurate rates "does not exist".

In April 2015, the top decision-making body of the Financial Conduct Authority, the Regulatory Decisions Committee, accepted arguments from former UBS trader Pete Koutsogiannis that requests made for high or low Libor submissions were not improper if they were within a range of accurate estimates of the cost of borrowing cash. He was exonerated.

In 2017, John Ewan, the former Libor manager at the British Bankers' Association (BBA), testified at the trial of two former Barclays traders, Ryan Reich and Stelios Contogoulas, that if requests asked for high or low Libor submissions within a range of interest rates at which the bank might borrow, it was within the rules. The defendants were acquitted.

'We were toast'

At Connolly and Black's trial, the DoJ's case was that fraudulent statements were made to the BBA. Yet the Department of Justice called no BBA witness and did not seek documents from the BBA until after Connolly and Black were indicted.

"It wasn't interest rates that were rigged. It was our investigation and prosecutions," Connolly said. "It didn't matter that the judge accused prosecutors of lying. It didn't matter that a government witness was told by prosecutors to sign a sworn statement that was false.

"It didn't matter that the DoJ never even contacted the British Bankers' Association which ran Libor until a year after we were charged. All they had to do was tell the jury what our bonuses had been and we were toast."

From 2010 until the trial, Deutsche Bank's leadership co-operated so closely with the US government that the investigation was outsourced to Deutsche Bank's lawyers, Paul Weiss.

In 2015, Deutsche Bank agreed to pay a record fine of $2.5bn to the DoJ and other regulators, with a 30% discount for "co-operation". The FCA said senior managers were directly involved in much of the "misconduct". However, only Connolly and Black were prosecuted.

It was undisputed at the trial that Deutsche Bank senior managers, including Anshu Jain, Alan Cloete and David Nicholls, encouraged derivatives traders and Libor submitters to share information about trading positions, seating them close together.

When he was told in April 2016 he was in line to be prosecuted, Matt Connolly was shocked and thought it was a mistake. When they announced the 2015 fines, regulators confirmed that sharing information was encouraged by senior management in London.

Deutsche Bank said: "As we stated in April 2015, no current or former member of the Management Board was found to have been involved in or aware of the trader misconduct."

The BBC has accumulated evidence, not shown to the juries in the rate-rigging trials, that much larger Libor requests, seeking to move Libor regardless of the accurate rates at which banks were borrowing, were made from the top of the financial hierarchy during the financial crisis.

However, prosecutors on both sides of the Atlantic have chosen to charge not central bankers nor senior managers but only staff further down the banks' ranks and money brokers.

- Published10 April 2017

- Published9 March 2017