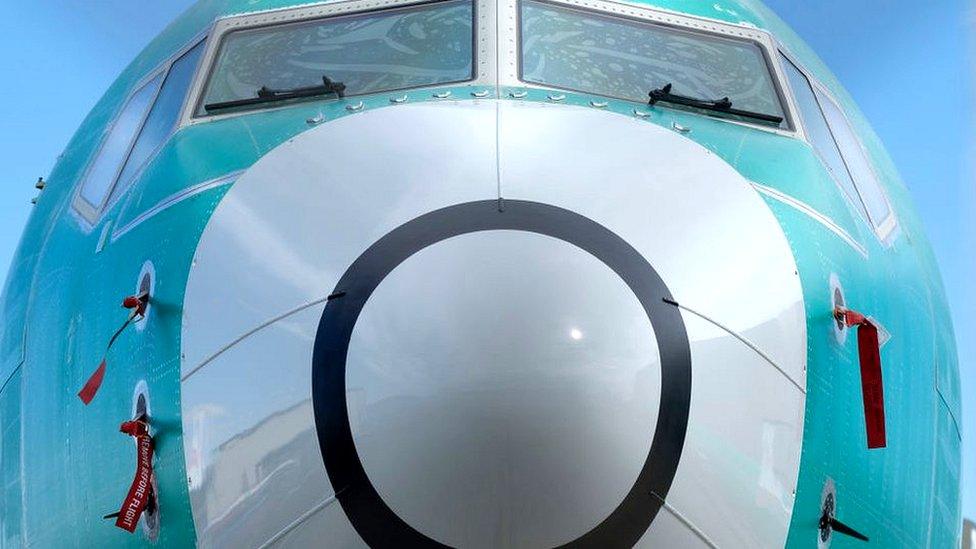

Boeing 'misjudged 737 Max pilot reactions'

- Published

Boeing needs to pay more heed to how pilots react to emergencies in its safety assessment of the 737 Max plane, US transport chiefs have said.

The 737 Max has been grounded since March following two fatal crashes.

The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) must decide if the plane is safe.

But according to the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the crews in the fatal crashes "did not react in the ways Boeing and the FAA assumed they would".

The 737 Max plane has not flown commercially since an Ethiopian Airlines aircraft crashed shortly after take-off on 10 March, killing 157.

It followed a Lion Air crash on 28 October last year which killed 189.

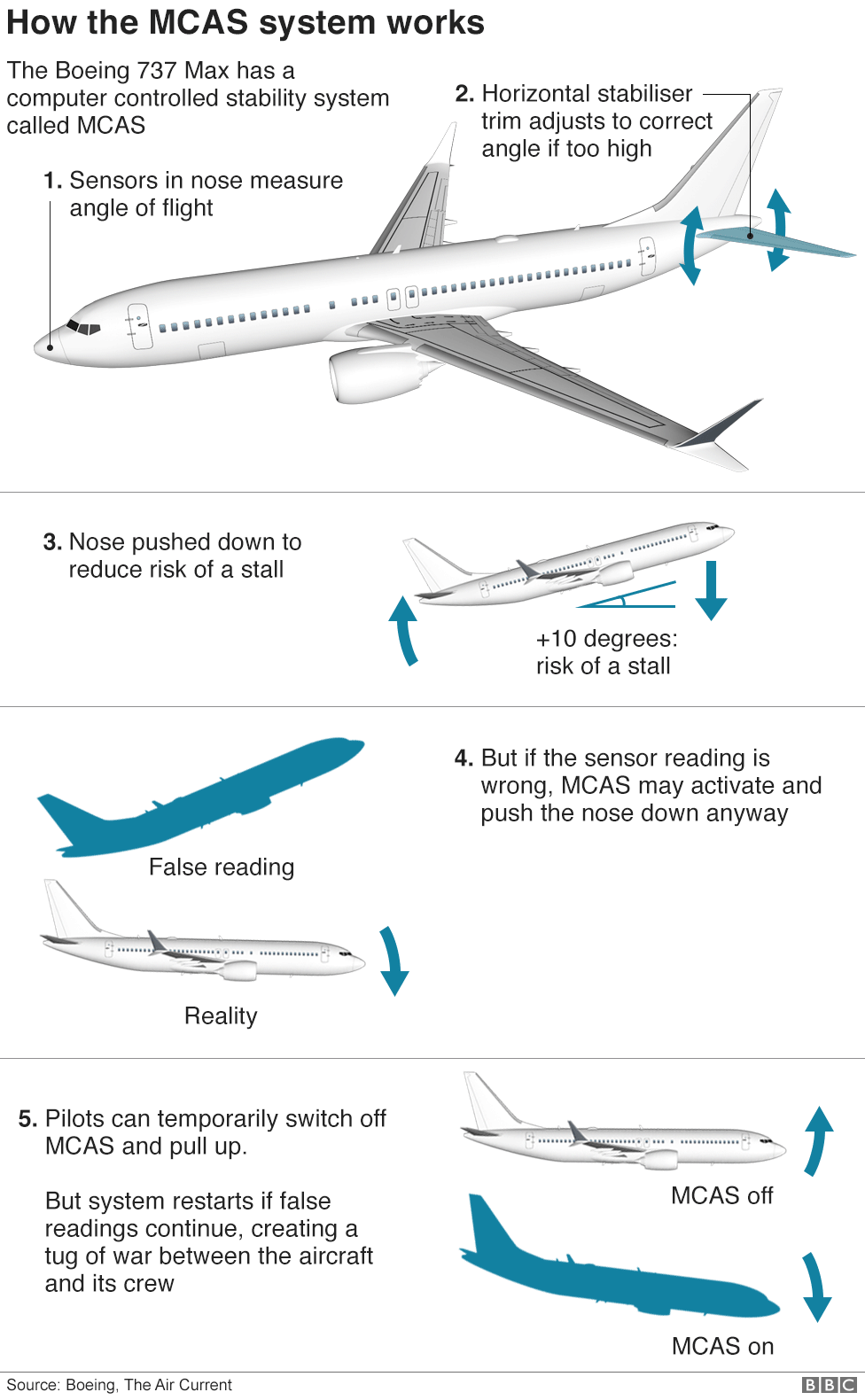

In both incidents, investigators have focused on the role played by a software system called MCAS (Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System), which was designed to make the aircraft easier to fly.

Inquiries have shown the software - and the failure of sensors - contributed to pilots not being able to control the aircraft.

Boeing has said it is revising the plane's software to improve safeguards.

But the director of the NTSB's Office of Aviation Safety, Dana Schulze, said Boeing "did not look at all potential flight deck alerts and indications that pilots might face when this specific failure condition occurred in Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines".

Earlier this month, Europe's aviation safety watchdog, the European Aviation Safety Agency (Easa), said it would not accept a US verdict on whether the 737 Max was safe.

Instead, it will run its own tests on the plane before approving a return to commercial flights.

"I think the crew were just overloaded with information". This was what a pilot in Ethiopia told me earlier this year when we were discussing the 737 Max that crashed near Addis Ababa.

The NTSB's recommendations seem to bear out that theory. It says that during simulator tests, Boeing assessed pilot responses to a generic MCAS failure. But it did not incorporate the kinds of problems that could lead up to such a failure.

This meant that when the real thing happened, pilots were faced with a variety of alerts and warnings that had not occurred in the simulator - linked to the sensor failure that caused MCAS to deploy at the wrong time.

As a result they did not respond in the way Boeing had assumed they would, and did not immediately take the steps it had assumed they would take.

Given that those assumptions underpinned the manufacturer's own safety analysis, it is a worrying conclusion, and potentially one with wider implications.

- Published5 September 2019

- Published13 August 2019

- Published17 May 2019