Thomas Cook: How the collapse affected me

- Published

When Thomas Cook collapsed on Monday, the effects were felt across the world as tourists scoured for information on how to get home and many staff, despite having lost their jobs, stoically helped them.

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) hired 45 jets to bring holidaymakers back, with only 5% of them so far delayed by a day or more.

During the coming days it will bring back the remainder of the 155,000 UK holidaymakers stuck overseas.

As well as workers and customers, the collapse hit suppliers such as hotel owners and will have created a hole in the supply of holidays.

The holidaymaker

Julia Jones, an education consultant, was on holiday exploring Greek islands when the news broke. Her husband returned on Wednesday, but she had to return on Thursday.

She travelled to the island of Skiathos, from which her flight was booked, in order to be ready when the CAA posted details of her new flight.

While information was available on the CAA's website, constantly monitoring it while relying on wifi in the hotel lobby proved less straightforward, she said.

At 05:00 on Wednesday the website showed their flight was due to leave that day, so the couple headed to the airport.

As more people arrived, "there was a lot of confusion," she said. And when she approached the airline desk, she found out her husband had not been placed on the flight list.

"We had people being split up," she said. "There was no rationale to the allocation of the boarding passes."

"And then the Thomas Cook reps turned up and sorted it all out," she said. "They were really positive, really helpful. We had a whip-round for them because they'd been so brilliant and then they cried."

Ms Jones gave her boarding pass to her husband so he could meet his work commitments, and she caught a flight the next day to Gatwick, rather than Bristol, and then boarded a bus to complete her trip.

The hotelier

Panos Andritsopoulos owns the Kanapitsa Mare Hotel and, with his family, helped develop the Greek island of Skiathos as a tourist destination from the 1970s.

Thomas Cook brought about 10-15 flights a week to the island, and British tourism delivered about half its tourists, he estimates.

"I don't think anybody got any money after July," he said, of him and his fellow hoteliers. While customers pay in full before taking off, hotels receive their payment 60-90 days after departure, he added.

The UK travel industry's insurance scheme will step in to pay for guests at his hotel for the period after Thomas Cook went bust. But for payments for holidays taken before Monday, he says he doesn't hold out much hope of ever seeing what he is owed.

"The government and banks were lending them money without checking," he said. "They are the ones that should be paying for this."

The island also suffered when travel firm XL Leisure Group went under in 2008, he said. Money was not recovered then, either.

"Nobody knows yet" about whether his or other hotels on the island will survive, he added. Other companies will step in to book his rooms, but competition keeps people coming to the island.

The worker

Rachel Murrell, who worked her way up to cabin manager during a 20-year career at the airline, says she found out about the firm's demise from a WhatsApp group with colleagues. "To this day I haven't even got a letter from Thomas Cook telling me what's happened."

Former Thomas Cook staff plan to protest in London next week, and Ms Murrell says she will walk from her home in Devon with her dog Pip to join them.

"I sat around moping and crying for two days and then I just got really angry, and I thought how can such an esteemed business that's 200 years old go bust overnight like that?" she said, as she started her walk.

"In my job role of 20 years I was always held accountable for my actions and I believe somebody is accountable for this," she says.

She also wants to highlight the plight of her colleagues, some of whom are couples who have both lost their jobs. The collapse came a week before payday and the due date for rent and mortgage payments for her and her co-workers.

Ms Murrell adds that she will try and find a new job in time, but wants answers first.

The boss

Peter Fankhauser, chief executive, said he was "deeply sorry" about the firm's collapse and said the company had worked "exhaustively" to salvage a rescue deal after it collapsed on Monday.

In the run up to the collapse, he led efforts to secure funding for the business, including a final effort to get a £250m UK government bailout.

The firm's lenders told him he needed to find £200m of emergency funding if they were to keep it going. No funding emerged, and the company went into liquidation in the early hours of Monday.

Mr Fankhauser was a veteran of the company, having joined in 2001 from upmarket Swiss rival Kuoni.

As he progressed through the company he was credited with improving the fortunes of its UK and European business - a plan which involved cutting 2,500 UK jobs - for which he was promoted to chief operating officer in 2013.

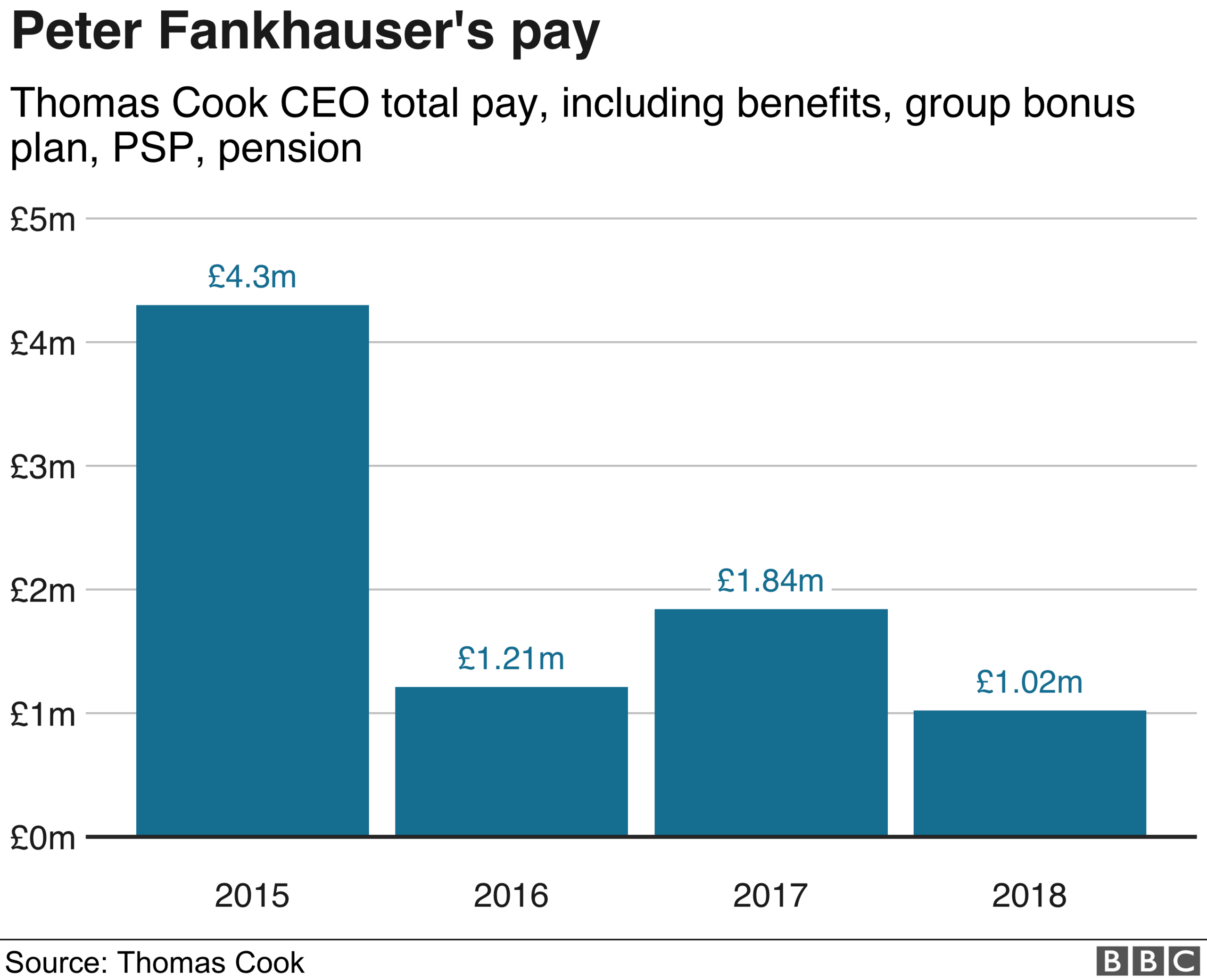

He has pocketed £8.3m in pay and other sweeteners since he was promoted once more to chief executive in 2014, including a £2.9m bonus in 2015.

When he took over from his boss Harriet Green, he said: "I am determined to work with all our great colleagues worldwide to build on Harriet's achievements, continuing to deliver great holidays for consumers and good returns for investors."

He didn't respond to a BBC request for comment.

- Published27 September 2019

- Published23 September 2019

- Published30 September 2019