Wheels of fortune? A new age for electric motors

- Published

When it comes to making electric cars better, it's the batteries that you'll hear about the most.

But what about the motor that actually drives the car?

Car enthusiasts have long-obsessed about what is under the bonnet of a traditional car, but in the electric world the motor gets little attention.

That might be about to change, according to Dave OudeNijeweme, head of technology trends at the Advanced Propulsion Centre (APC), a joint venture between the UK government and the automotive industry.

He says improvements in motor technology are set to have a profound effect on the performance of electric vehicles in the coming years.

"Electrification is based on three main pillars: batteries, electric motor and the powertronics [the power management system]," he says.

"It's not all about batteries. They do get a lot of headline news but the motors and the powertronics are absolutely key."

And with new technologies, from 3D printing to in-wheel motors (IWMs) that allow a car to spin on the spot, electric motors could be grabbing more of the limelight.

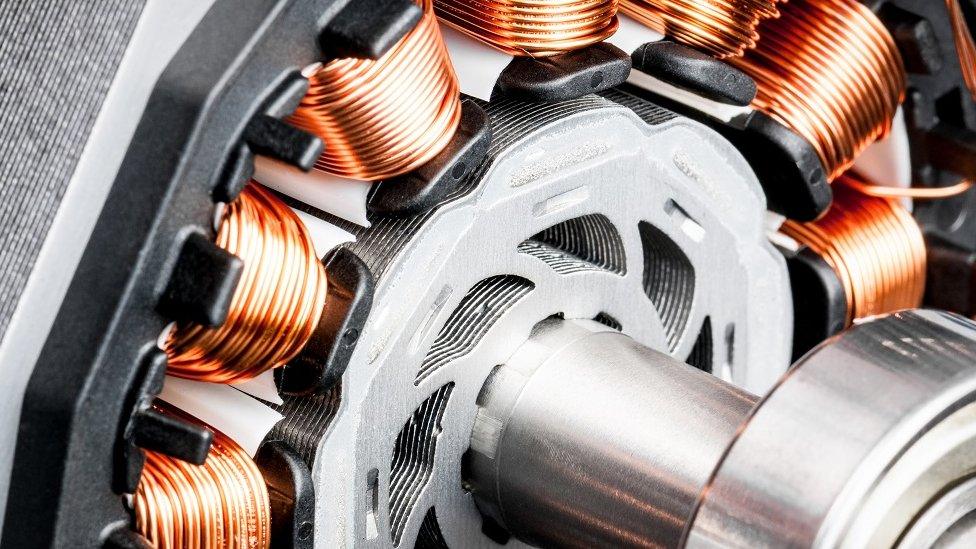

Improvements in motor technology will mean profound improvements on electric vehicles' perfomance

Most electric car motors follow the same basic principles, tightly wound coils of wire interact with powerful magnets to create rotation.

But despite a relatively simple set-up, there's still plenty of room for improvement.

"The power of a motor goes up with its speed. What you want to do is spin it as fast as possible in order to make it as small as possible - but then you get into problems of cooling," says Ian Foley, managing director of British motor manufacturer Equipmake.

"The limitation now on how you improve the performance of electric motors, is how effectively you can get the heat out of them."

Equipmake's solution is to rearrange the motor's magnets so that they're positioned like the spokes of a wheel.

This not only increases torque (the force which causes rotation), says Mr Foley, but also makes the magnets more accessible, so that cooling water can be run directly over them.

The company is also now using additive manufacturing - 3D printing - to improve cooling and also cut costs.

"There are two main benefits we'll get from additive manufacturing. One is that you can integrate multiple components, so you end up with a much lower component count because things that would previously have been bolted together are all in one piece," says Mr Foley.

"The other main thing is the issue of cooling.

"In order to cool you need much more effective heat exchanges, and with additive manufacturing you can effectively increase the surface area inside the motor for the cooling surfaces and therefore get much greater cooling potential."

One of the key challenges is keeping future high-performance electric motors cool

The company is expecting to have its motors in production in around 18 months' time, initially selling them for use in supercars and electric buses - where they're efficient enough to be able to run all day on a single charge. It has already signed a deal with Brazilian automotive manufacturer Agrale.

And other manufacturers are thinking about a more radical shift.

In most electric cars, the motor is found on one axle and in four-wheel drive cars there will be two motors, one on each axle.

But some companies are working on a radical redesign, placing motors in the wheels themselves.

According to Chris Hilton, CTO of Protean Electric, in-wheel motors improve handling because the performance of each wheel can be finely controlled.

"They also lower the overall centre of gravity and help to reduce weight and optimise weight distribution in the vehicle," he says.

In-wheel motors like this can improve handling as they allow you to control the performance of each wheel, says Protean

"Also, because IWMs are located in the wheel, there are minimal losses in transmission of the torque to the road, meaning they are more efficient. This means greater vehicle range, or the same range from a smaller battery."

Protean's technology is currently being tested by manufacturers of passenger cars, commercial vehicles and even autonomous "pods".

Another firm working on in-wheel motors is Japan's Nidec, which announced its prototype earlier this year.

According to Nidec, the motor has a long list of advantages, not all of them obvious - less noise, for example, thanks to fewer moving parts.

But perhaps the biggest advantage is space. "Cars that use in-wheel motors don't need a motor compartment," says the firm.

Experts say that in ten years electric motors will be unrecognisable from today

"Also, with the elimination of the drive shafts, the wheels can rotate freely. For example, it becomes possible to rotate the wheels 90 degrees and drive to the left or the right, or even rotate in place, instead of just driving forward or backward. This adds another dimension to how the car can move around and makes it easy to navigate tight spaces."

APC has set out a roadmap of how it sees electric motors developing; and, by 2025, it expects costs per kilowatt to almost halve, while power density triples.

"For the same amount of power they generate, they'll weigh a third as much and be one third of the package size as well. At the same time the costs will reduce," says Mr OudeNijeweme.

"The electric motor will dramatically change. I don't know how quickly, but ten years from now it will be unrecognisable from what you see today, not in how it looks - but in what it does."