Brexit: Could the UK and EU sort a trade deal in months?

- Published

The central element in the Conservatives' election pitch is a commitment to "get Brexit done".

Boris Johnson's Withdrawal Agreement with the EU would indeed end the UK's membership.

But it would leave some very important Brexit-related challenges still to do, including the UK's future trade relationship with the bloc, and with the rest of the world.

Some people are worried that we might face a new "cliff-edge" at the end of 2020.

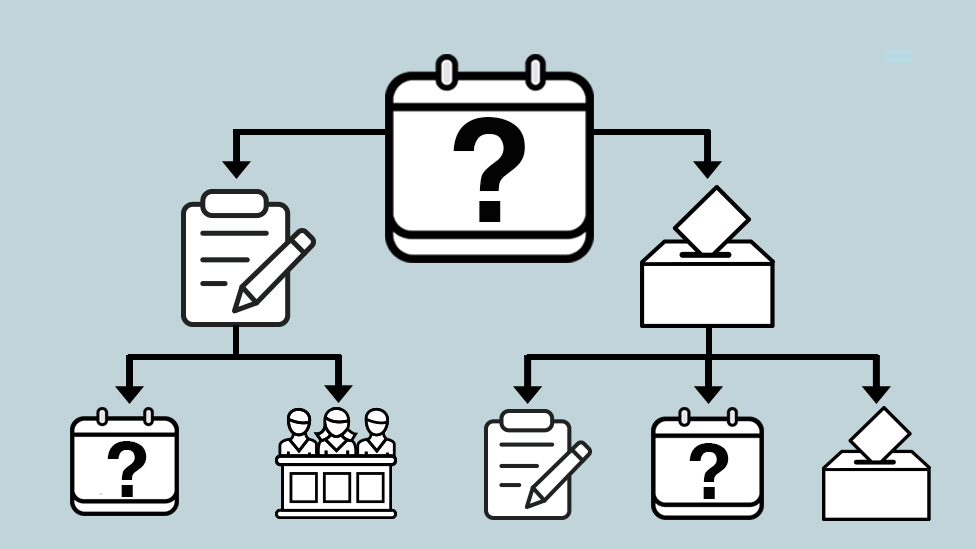

What might happen next year?

Under Mr Johnson's Withdrawal Agreement, the existing arrangements between the EU and UK would temporarily continue, with goods and services being allowed to flow freely across the various borders with the continent.

That arrangement is due to end on 31 December 2020.

If Boris Johnson wins a majority he says he would negotiate a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU ready to go into operation at the end of 2020.

An FTA is an agreement between two countries which eliminates trade taxes, known as tariffs, with the aim of making business and commerce run more smoothly. FTAs often also include measures to reduce other types of regulatory barriers that make trade more difficult.

Is there enough time to negotiate a trade deal?

The aim is to have a deal done in time for the end of 2020. That is a very challenging timetable.

Trade negotiations tend to take several years to complete. They are technically challenging and politically contentious. Both those features can make them drag on.

To take one example, the EU's deal with Canada took more than five years for negotiators to complete and another three before it came into force, on a provisional basis.

The UK-EU negotiation will be unusual in that it is intended to establish a trade relationship that is less integrated than what the two sides have now.

Usually, trade negotiations make for closer commercial relations, so past experience isn't necessarily a good guide to the likely timetable.

Some people say that because we are already fully aligned with the EU the negotiation will be easy and quick.

But for many Brexit supporters the freedom to depart from EU rules is one of the main prizes. How much we depart - on food standards for example - will be important for the EU in judging what restrictions to impose on British goods. That could be a time-consuming process.

Trade deals with the US have run into trouble over issues such as chlorine treated chicken

Could we extend the current arrangements beyond December 2020?

Yes. There is a provision in the Withdrawal Agreement to extend the transition period by one or two years, but that decision must be taken by 1 July.

So there would only be a few months of negotiating time before an extension would need to be agreed. Will there have been enough progress by then to allow us to be confident that it can all be done in another six months?

After that date an extension could not be done with the arrangements in the Withdrawal Agreement. The Agreement itself would have to be amended or a new treaty agreed. There is some debate about whether that would be legally possible.

What happens if there is no FTA by the end of the transition period?

If there is no agreement the trade relationship would default to what is known as World Trade Organization (WTO) terms - which is what trade relations would be if we left the EU now with no deal.

WTO terms mean British exporters would have the same access to the EU as do other countries with no trade agreement.

That means the EU would apply to UK goods the same tariffs it applies to goods from the US or China for example.

For cars that would be 10%. EU tariffs are particularly high for some agricultural products. British exporters would also face regulatory barriers they currently don't.

If we do get a trade agreement, what would it mean in practice?

UK exports would not face tariffs going into the EU. Whether they would have to go through some checks and tests to show compliance with EU rules would depend on exactly what was agreed.

So exporting could involve more red tape and more costs for UK firms.

This is one reason why many economists think the UK economy will be smaller with this kind of deal than it would have been had we stayed in the EU.

How easily services businesses could supply clients in the EU would depend on the extent of regulatory alignment and on what agreement can be reached on working and travelling across borders.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

Can we have an FTA with the US if we have one with the EU?

It would probably be more difficult. One clear potential trouble spot is product regulations, especially food standards.

The US and EU tried to negotiate a wide ranging deal that ran aground partly on that issue.

There were particular issues about chlorine-rinsed chicken, growth-promoting hormones used in beef production, and genetically modified (GM) foods.

The US wanted to be able to sell these foods (or to do so more easily in the case of GM foods) in the EU. The EU wouldn't agree.

In a UK-US trade negotiation, the Americans will want easier access for their foods to the UK.

The EU would be very wary of any such foods in circulation in the UK finding their way into the EU's single market.

If they thought that was a risk they would be more reluctant to allow unrestricted access for UK goods, lest some of the controversial US food should get in.

If we don't get a FTA with the EU is that a "no-deal Brexit"?

The term "no-deal" was often used to mean no withdrawal agreement. So the scenario of no FTA at the end of next year is not no-deal in that sense.

Ratifying Mr Johnson's deal would mean an agreement covering citizens' rights (EU citizens here and British on the continent) the financial contribution and the Irish border.

But "no deal" is also sometimes used as meaning no trade agreement and a WTO terms trade relationship with the EU and that scenario is a possible outcome of Mr Johnson's approach.

- Published13 July 2020

- Published21 October 2019

- Published23 January 2020