Why ministers won't release Brexit forecast

- Published

EU leaders must decide whether they will grant a Brexit extension

Chancellor Sajid Javid has refused to recalculate Treasury assessments on the impact of the government's Brexit deal, saying it is "self-evidently in our economic interest".

But the missing economic impact assessment is a symptom of a rather large elephant in the room.

That is the fundamental strategic choice, made by this government, to pursue unfettered free trade deals with the US and others, at the expense of extra trade barriers with our biggest trade partner - the EU. This also creates some trade friction even within the UK - between Great Britain and Northern Ireland and vice versa.

Boris Johnson's Brexit plan is aiming for a significantly different economic landing point to that of Theresa May.

While the renegotiation was ostensibly to get rid of the backstop to get around the concerns of the DUP, this version has angered the government's partners even more. That is because it creates new trade frictions within the UK single market, between Northern Ireland and Great Britain.

How did the prime minister in seeking to get the DUP onside, alienate them further?

It is because he and his part of the Conservative Party loathed the backstop for a different reason from the DUP.

The backstop functioned not just as a means to ensure existing border relationships within Ireland, but also as a limit on the economic distance between the UK and the European Union for many years into the future.

It promised to align regulations with the EU in many sectors, and adopted a series of legally binding "level playing field" arrangements covering the environment, employment, and competition.

But it also limited the ambition in other free trade deals with, for example, the US and other partners. By implicitly aligning tariff rates with the EU and sharing regulatory standards in many areas, Theresa May went out of her way to promise alignment to industries - such as automotive, aerospace & pharmaceuticals - at the expense of freedom over other deals with partners who would prefer a more flexible approach.

Not rocket science

There are two reasons why there is no economic impact assessment being published. First, it would take longer than a few days to do one. And second, because the assessment would almost certainly show that the medium term trade off for the UK is negative for growth.

Some industries will benefit from a more expansive free trade policy

It isn't rocket science. A more distant economic relationship will silt up some supply chains and break others. Those industries that have been built up on total alignment of everything across the EU over years and decades, particularly in advanced manufacturing, will get hit by extra customs checks on the origin of parts, food regulations, and safety standards.

The flip side is that a more expansive free trade policy, with the US and others, will create some winners too - perhaps in some parts of financial services, tech, elements of cutting edge medical research, and in small businesses that do not rely on trade with the EU. Most of the bigger positive impacts will take longer to be realised.

The Treasury does have the economic models to calculate this. External economic experts have done so too seeing a hit of 2.3% to 7% over a decade in the size of the economy per person (GDP per capita).

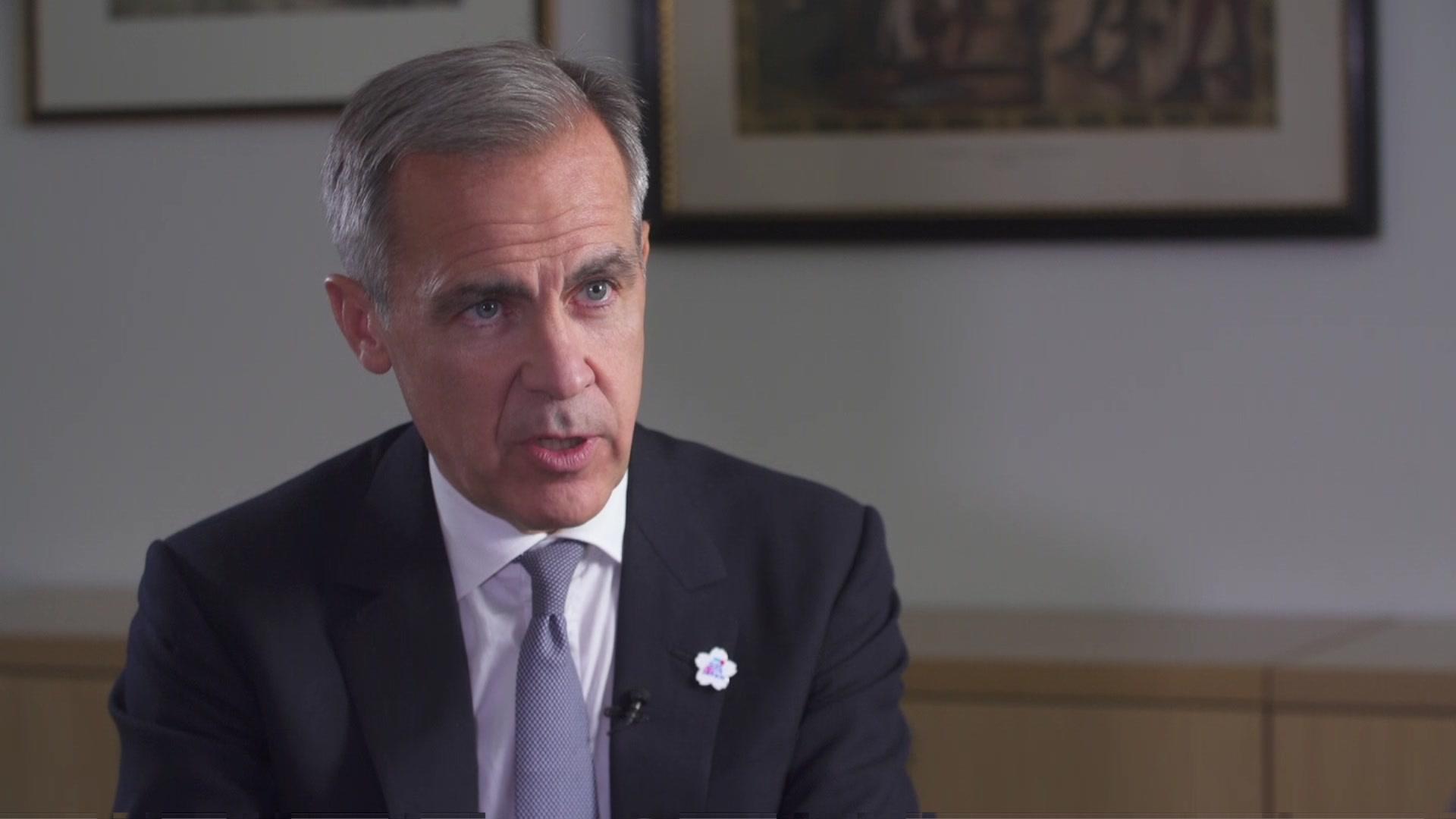

Mark Carney told the BBC that Boris Johnson's deal "takes away the tail risk of a disorderly Brexit".

The Bank of England last year did a study modelling two types of economic partnership: "close" - ie that of Theresa May, and "less close", an arrangement which shares some characteristics with the current Withdrawal Agreement (customs checks on UK-EU trade by 2021, additional regulatory barriers).

The difference between the two was worth 2% of the size of the economy over a half decade in last year's assessment. Importantly the modelling enabled Bank of England governor Mark Carney to pronounce last year that the Theresa May deal would see a slight boost to the economy.

He did not repeat that endorsement when I questioned him at the IMF meeting in Washington DC this weekend. Indeed he said that the Boris Johnson deal did not "overlap" with the closest and deepest possible version of the Theresa May deal.

Where nearly everyone agrees is that no deal would be worse for the economy, by leading, immediately to even more acute versions of the tensions described above.

Trade-offs

So the government is instead focusing on comparing its deal to no deal. Indeed the chancellor said in a letter to the Treasury Select Committee that it was "self-evidently in our economic interest". The government does not want to compare it to Theresa May's deal, and definitely not to any type of remain option.

What gets lost here, though, is an eminently reasonable debate about the trade-offs involved in the shape of a future relationship.

A more aligned relationship with the EU would be better for those existing workers and companies in industries that have been built up on that basis. A less aligned relationship could, in theory, benefit those in more global, less-regulated service industries.

Some argue this can all be sorted out after an election. The Withdrawal Agreement Bill, and draft treaty, say ministers, can only negotiate a deal consistent with the revised political declaration, which deleted some references to ongoing alignment, and removed the detail of level playing field arrangements.

Economic forecasts can help to illuminate those trade-offs. The country is not going to get them, from the government at least.

- Published19 October 2019

- Published18 October 2019