UK wage growth slows as unemployment falls

- Published

- comments

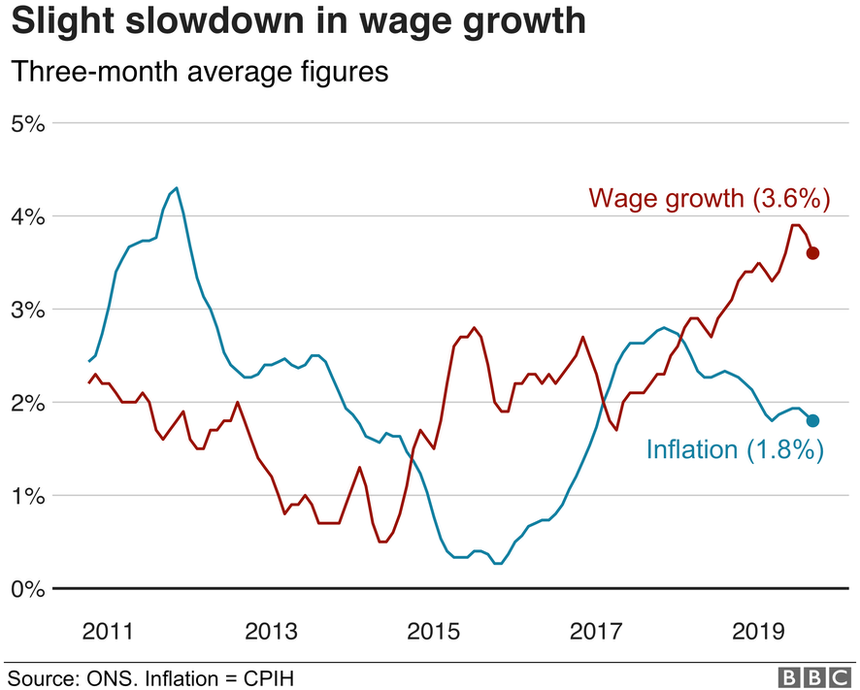

UK wage growth slowed down in the three months to September, according to the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS)., external

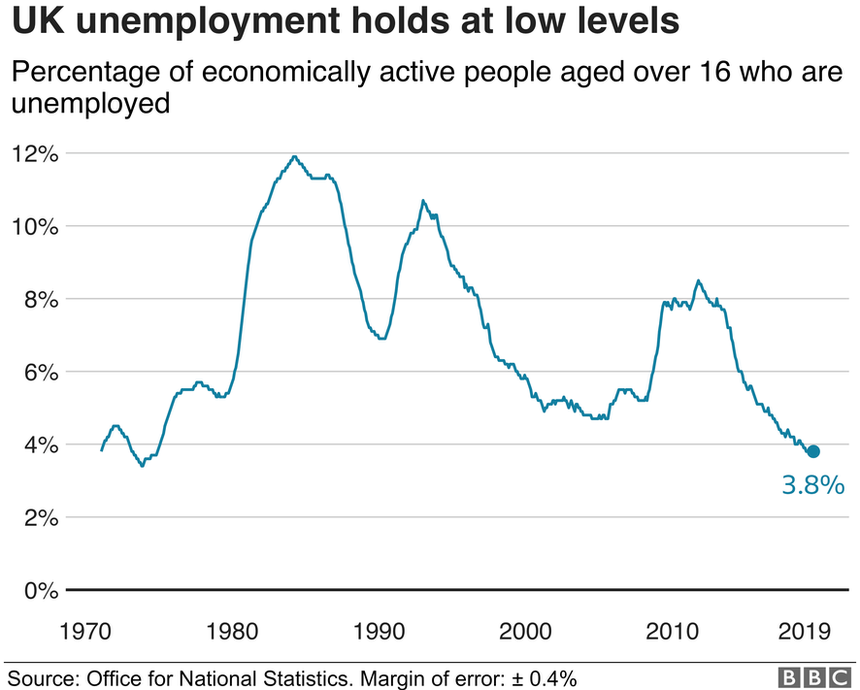

Unemployment dropped by 23,000 to 1.31 million over the same period, while the number of people in work also fell.

Average earnings excluding bonuses increased by 3.6%, compared with 3.8% growth in the previous month.

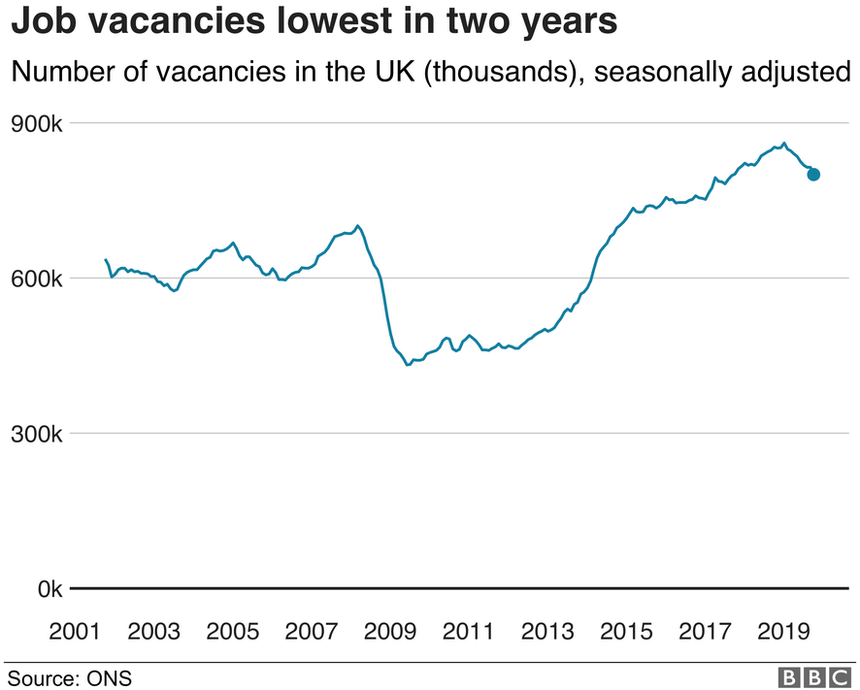

The figures also showed the biggest annual drop in the number of job vacancies in nearly 10 years.

The ninth consecutive monthly fall in available jobs saw advertised positions fall by 18,000 to 800,000.

There were 32,75 million people in work during the three-month period, a fall of 58,000. It was the biggest drop since May 2015, when the total fell by 65,000.

The ONS said this was down to falling numbers of people working in retail, after the collapse of several store chains and the implementation of shop closure programmes by other firms.

Average weekly pay, in real terms before tax, was £470.

"The employment rate is higher than a year ago, though broadly unchanged in recent months. Vacancies have seen their biggest annual fall since late 2009, but remain high by historical standards," said an ONS spokesperson.

"The number of EU nationals in work was very little changed on the year, with almost all the growth in overseas workers coming from non-EU nationals."

It comes after last week's news that the UK's economy had grown at the slowest annual rate in almost a decade.

Samuel Tombs, economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said the figures were likely to mean interest rates would stay unchanged for the foreseeable future.

"The pace of weakening in the labour market remains gradual enough for the Monetary Policy Committee to hold back from cutting bank rate over the coming months," he said.

Beware the rollercoaster of employment figures

Analysis by Robert Cuffe, BBC head of statistics

How do we know whether any month's change is a blip or a turning point?

Estimates of employment are based on a survey and so come with a margin of error.

The ONS say not to worry about changes smaller than 150,000 people.

But every monthly change in the unemployment rate has been smaller than the margin of error for ten years.

So we have to get a feel for the underlying picture by combining figures like unemployment with other measures like wages and job vacancies and using judgement.

But be warned.

If anyone could time a turn in economic conditions precisely, they'd be too busy getting rich to tell you.

So pay most attention to the long, slow trends.

IHS Markit economist Chris Williamson said the falling numbers of working people and job vacancies showed data "was falling into line with earlier warning signs of a weakening labour market from the surveys".

He added: "Recruitment agencies reported that the demand for permanent staff at employers had grown at the joint slowest rate for a decade in October, as uncertainty and worries about the outlook reduced firms' appetite to take on extra employees."

Andrew Wishart, UK economist at Capital Economics, said: "Overall, the figures appear to illustrate that demand for labour is easing, but no sharp downturn, which is a relief following disappointing GDP growth in the third quarter."

Tej Parikh, chief economist at the Institute of Directors, warned that wage growth could continue to slow down.

"The pick-up in wage growth earlier this year has been a plus, but there is clearly a limit to how high pay packets can go. With many firms facing elevated costs and difficulties raising their productivity game, the margins to raise pay are eroding. A further acceleration in wages now looks unlikely," he said.

- Published11 November 2019

- Published7 November 2019