Downloading: 'People said it would end record labels'

- Published

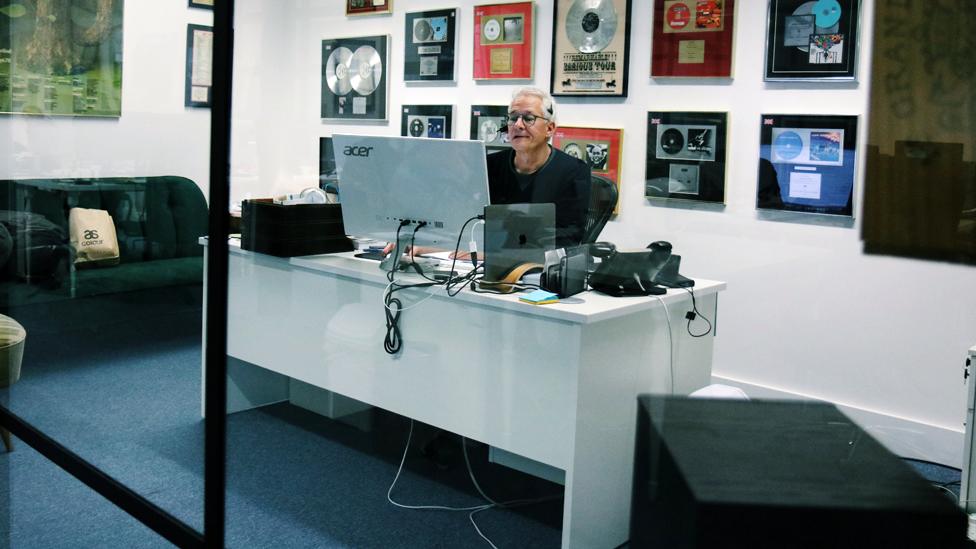

Jeremy Lascelles has now worked in the music industry for 47 years

The BBC's weekly The Boss series profiles different business leaders from around the world. This week we speak to UK music industry veteran Jeremy Lascelles, the co-founder and chief executive of Blue Raincoat Music.

Jeremy Lascelles says there was "total and utter panic" across the entire record industry when illegal music file sharing took off.

"People were saying it was the end of record labels, and that we had better close everything down, and sue absolutely everyone who was illegally downloading music. Everyone was taking the view that we were finished."

Speaking at his office in central London, he says the explosion of illegal downloading in 2000 terrified record labels. "It was such an obvious threat to our business model. And for probably the next 15 years the record industry did indeed go into a tailspin."

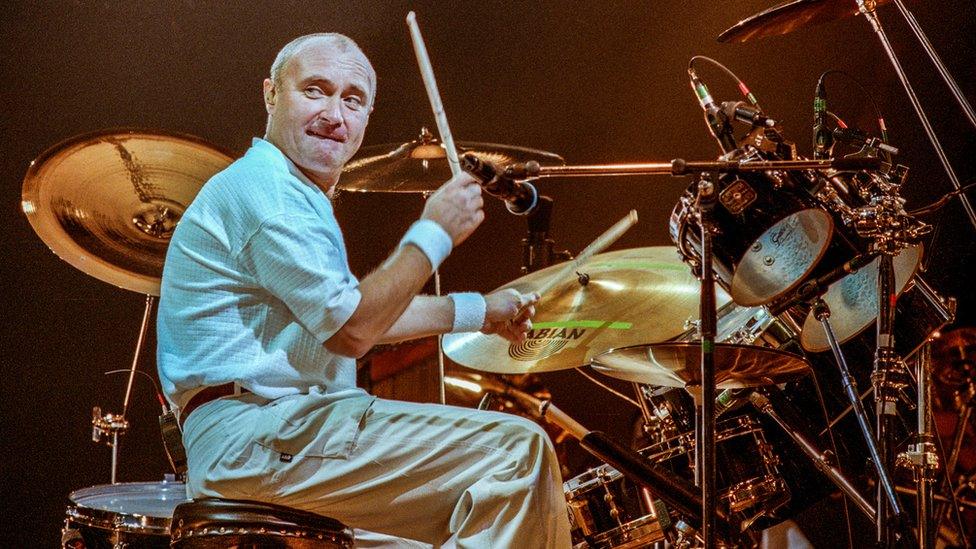

Jeremy was a close confidant to Phil Collins

At the time Jeremy was on the council of the BPI, the UK record industry's trade body. He was also the chief executive of music publisher Chrysalis Music.

While most of his colleagues at the BPI wanted to sue illegal downloaders, he argued against it. "The general view was to sue everyone, you know, even some granny in Swansea because her grandson had used her computer.

"I thought this was just insane, that the PR would be catastrophic and the genie was out of the bottle anyway," he says. "I didn't know what the solution was myself, but I knew that threatening people was not the way to solve things."

Born in London in 1955, Jeremy says he became obsessed with music from about the age of seven. "I had two older brothers, and we'd pool our pocket money to buy the latest singles or albums. You could get three singles for a quid."

In his late teens he dropped out of school to manage a band formed by one of his brothers. "The name of the group was the Global Village Trucking Company," he says. "I was tasked with booking them gigs. So I took a big bag of two pence pieces, went to the local phone box, and just started calling up pubs that had live music."

Jeremy then spent most of the 1970s as a tour manager for bands including Curved Air, whose drummer - Steward Copeland - went on to form The Police.

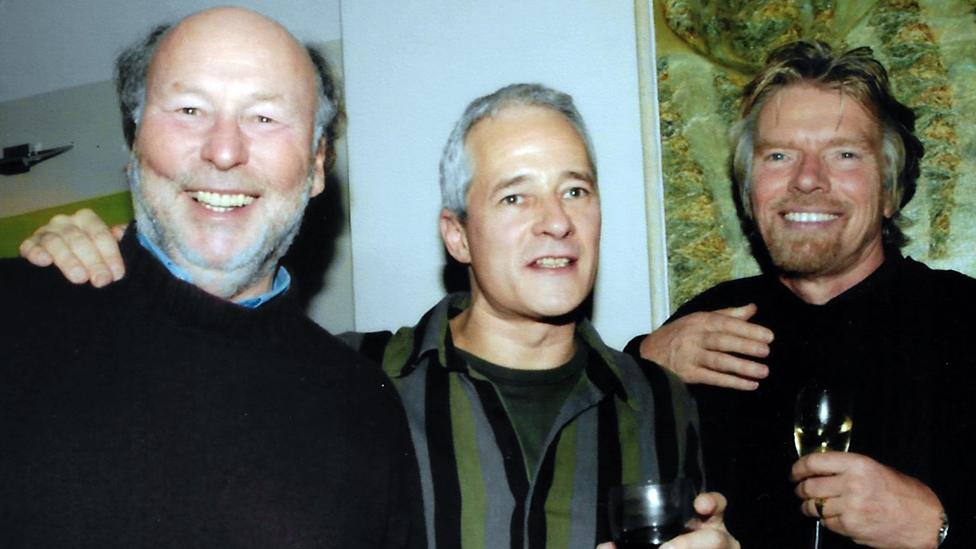

Jeremy had a big falling out with Sir Richard Branson (right)

In 1979 he was offered a job in the A&R department at Sir Richard Branson's Virgin, where he stayed for the next 13 years, rising to head that division. A&R stands for "artists and repertoire", and involves both finding new talent, and looking after the development of a label's existing artists.

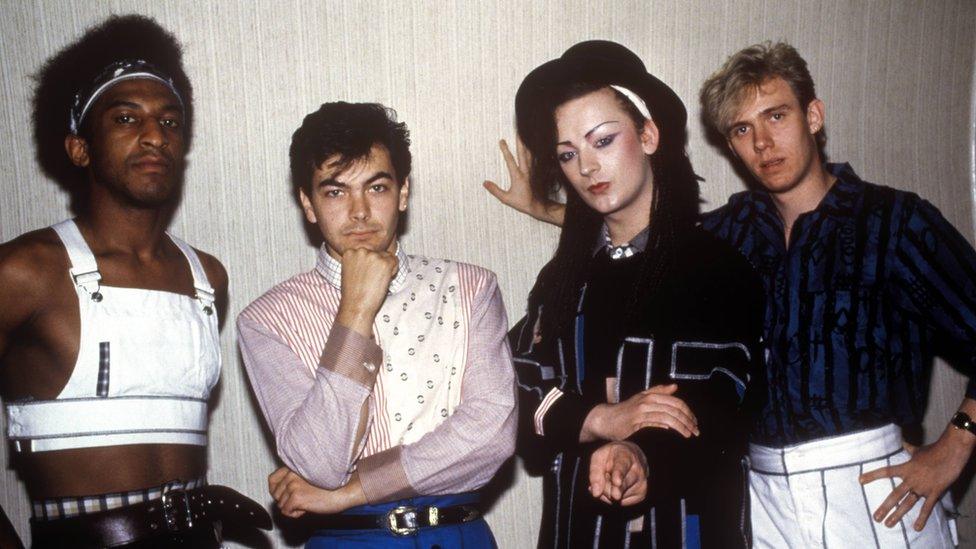

Looking back, he says the 1980s was "a great period for British pop music, a different world to today". During the decade record sales soared, further fuelled by the introduction of the compact disc, which meant that many music lovers bought CD versions of albums they already owned on vinyl or cassette.

During his time at Virgin, he worked with acts such as Phil Collins, Culture Club, the Human League, and Simple Minds.

"I worked very closely with Phil Collins in particular, and I have nothing but good things to say about him, he is a lovely man," says Jeremy. "Even at the height of his success he was quite insecure. He thought it could all disappear overnight.

"He used to send me demos of his songs to check out, and he'd say that I was the only person who would tell him anything other than the sun shines out of his proverbial.

"And Culture Club were in the office all the time. They'd just turn up unannounced, but you always knew when they were on their way, because a group of their really dedicated fans would arrive about 15 minutes beforehand, and stand outside."

His current business combines both artist management and music publishing, alongside running the Chrysalis record label

In 1992 Jeremy left Virgin shortly after Sir Richard had sold up to EMI, then the UK's largest record label. He admits that he and Sir Richard had a big falling out over the sale. "Richard had lost interest in the record label, he was obsessed with his airline by that point. We had a big, ugly row, but that's history."

After working as a consultant for a few years, in 1994 Jeremy took up the top job at Chrysalis Music.

Did he think that the record industry had got complacent by the time illegal music downloads burst onto the scene in 2000? "I don't think that we thought the good times would go on forever, but certainly we realised that they were good times."

More The Boss, external features:

After a number of years of real pain in the industry, he says it was effectively saved by Spotify and the other streaming services. "The record industry was incapable of thinking its way out of the trouble, and then music streaming just fell like a gift from the gods.

"Streaming has its critics, but it's just a different business model to selling physical records," says Jeremy. "It's a volume or nickel-and-dime business - tiny margins, but from huge streaming numbers.

"You do hear arguments from artists that they are not earning a lot of money from streaming, but that is probably because they are stuck on old contracts with their record labels. But if you are an artist who does direct deals with the streaming platforms then you can make good money."

Culture Club were signed to Virgin Records

But streaming has greatly reduced the importance of the record labels, he agrees, with power mainly transferring to the artist management companies. "An artist's manager is now at the centre of everything," says Jeremy.

While the global record industry has seen "a strong recovery" over the past five years, "we haven't yet, on a macro level, re-entered the glory years," says Tim Ingham, of trade website Music Business Worldwide.

"Don't forget that the annual revenue of the global record industry was essentially cut in half between 1999, circa $29bn [£22bn] and 2013, just under $15bn," he says. Yet with worldwide industry revenues topping $19bn last year "there's plenty of money to be made, and plenty of growth ahead," he says.

Jeremy was David Gray's music publisher, and stood by him during the barren years before Gray's White Ladder album was a smash hit in 2001

Since 2014, Jeremy has been chief executive of London-based Blue Raincoat Music, which combines both artist management and music publishing, alongside running the Chrysalis record label.

"It is a source of total, utter astonishment that I'm still working in the music industry after 47 or so years," he says. "I'm still getting paid to do what is essentially my hobby. I'm a very lucky guy."