Would a 'no deal' Tory government borrow as much as Labour?

- Published

- comments

The Labour Party freely admits that its manifesto would lead to a marked increase in government borrowing.

In general it deploys an argument used by all parties, including the Conservatives, that there is a global consensus stretching from the IMF to Brussels and Tokyo to borrow more at currently cheap government borrowing rates in order to invest to increase productivity.

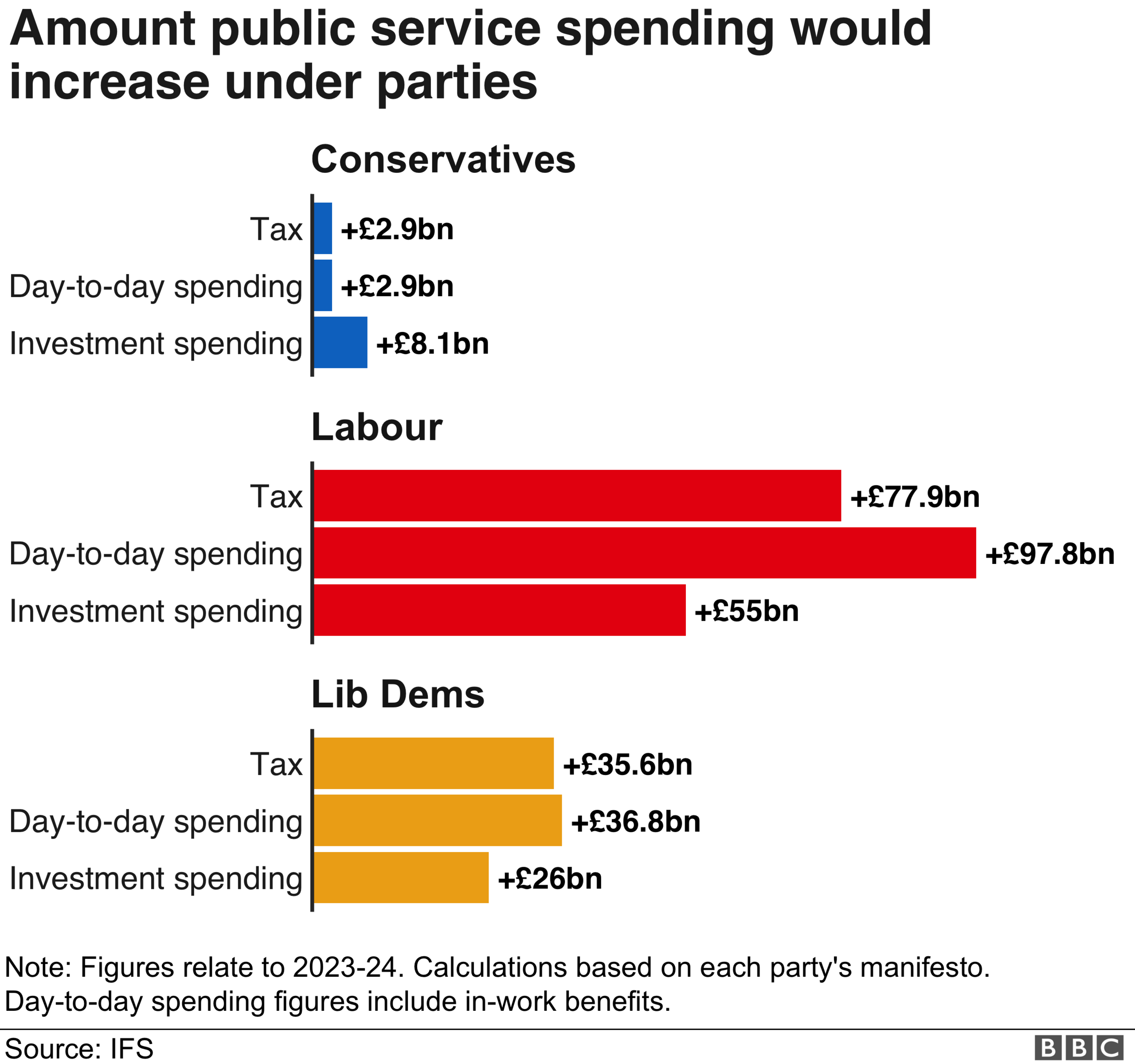

But it is borrowing all the same. At £55bn a year it is so much of an increase that Labour are yet to actually allocate it.

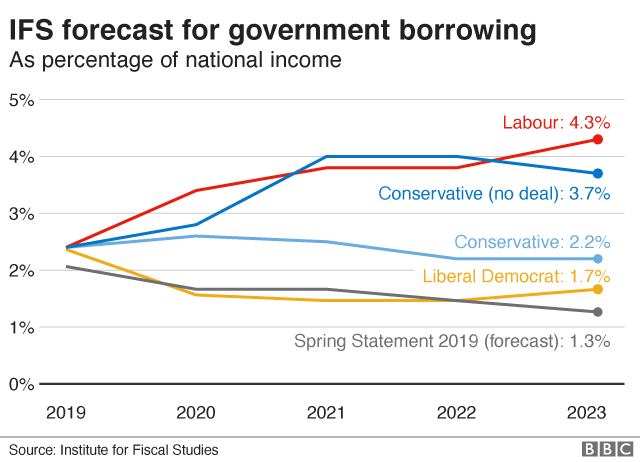

Add in the unfunded £58bn promise (£11bn a year) to compensate women state pensioners, and a reasoned expectation that Labour's plans will not raise £83bn solely off the rich and big businesses, and you get to annual deficit numbers of around 3.5% to 4% of GDP, according to both the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and the National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

The Liberal Democrat's fiscal plans, suggest borrowing of below 2%, according to the IFS, partly as a result of its aim to run a 1% surplus on day-to-day spending.

The big picture is that all the parties are comfortable with a persistent deficit, as long as it is being used to invest. But the numbers are different, with Labour borrowing notably more.

However, the IFS has also compared a plausible scenario of a no-deal Brexit in terms of the future trade arrangement by the end of the next year.

A version of no-deal Brexit is still on the table at this election, after the Conservative manifesto committed, in bold, "we will not extend the implementation period beyond December 2020".

Although the UK would have legally and formally left the European Union with a deal, including signing up to a £33bn exit settlement, it is unclear that a full tariff-free trade agreement could be negotiated and implemented before the end of next year.

While this would not be quite as disruptive as no deal without even a withdrawal agreement, as was being planned for on 31 October, it would involve the imposition of hefty tariffs on many UK exports, and some on imports too.

So the Conservative manifesto implicitly seeks a mandate to accept this as an outcome, even as the clearly stated objective is to get both a withdrawal deal passed by January and a new trade deal in place by December.

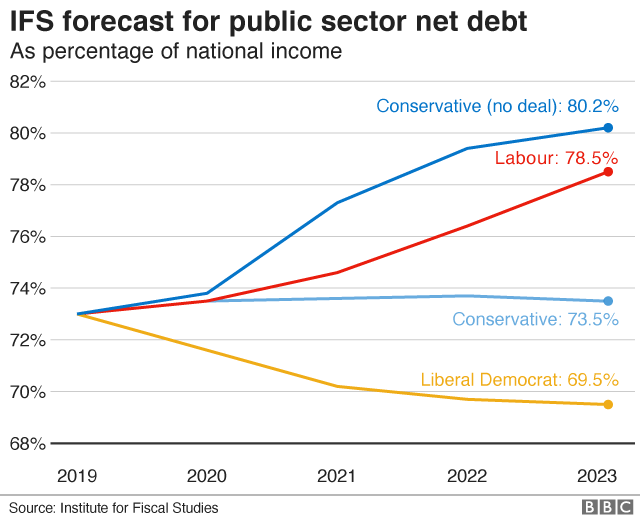

In that no-deal scenario, the IFS sees the national debt (the total amount of money owed by the government) as clearly higher under a Conservative no-deal outcome than under Labour, heading up to 80% of GDP.

According to the IFS, the deficit in this situation would also spike up to 4% of GDP in 2021-22, and 2022-23, just above predicted Labour borrowing, before falling back below Labour in the final year.

In fiscal terms, a no-deal scenario means that forecast borrowing jumps for the Conservatives to the same range as Labour's plans, and in some years a little higher (though not in every year as Thursday's original, subsequently corrected, version of this IFS chart suggested).

In July, the OBR modelled an International Monetary Fund (IMF) scenario of World Trade Organization (WTO) tariffs on the UK economy, and that stress test scenario suggested extra annual borrowing of £30bn a year or 1-1.5% of GDP, in line with the IFS scenario.

A Conservative source says that this is not a like-for-like comparison. The "no-deal" scenario is a worst case, that the party in government is not aiming for.

"This analysis is misleading. It models a hypothetical no-deal Brexit in a year's time, which clearly isn't government policy.

"But it doesn't model the economic impacts of Labour's actual plans for government, set out in black and white in its manifesto and elsewhere. There's a wealth of evidence to suggest that these plans would cause significant economic disruption," they say.

They argue that the IFS has not taken into account the negative overall impact on growth and business confidence of the Labour policies for spending, taxation and nationalisation.

If that is correct, Labour's deficits would end up far in excess of the 4% projected. But, say economists, there is no way to model this impact. The Conservatives also stress that they are confident of getting a deal.

But it was the PM who chose to include a path to WTO terms in his manifesto, at a time when such a commitment was explicitly sought by the Brexit Party. In effect the PM has rejected the one to two years flexibility on timing for a negotiated trade deal, available in his own exit deal.

It is also the case that a no-deal scenario at the end of the next year would not be quite as disruptive as it might have been at the end of October.

However, many of the models from the IMF and the Bank of England of the hit to the economy did not assume the most disorderly type of no deal.

Evidence from the car industry, external this week was that WTO terms tariffs would cost the UK car industry £3.2bn a year "which could not be absorbed", and lead to the loss of UK production of 1.5 million vehicles worth £43bn over the parliament.

So what can be said? Labour plans to borrow more than the other parties. But the economic consensus is that a WTO-terms Brexit relationship, that is not aimed for, but for which the prime minister and Conservatives have made explicit allowance in their manifesto, leads to borrowing of the same order, and overall debt higher in the next parliament than the amount Labour is actively planning for.

- Published27 November 2019

- Published24 November 2019

- Published21 November 2019

- Published20 November 2019

- Published11 December 2019

- Published6 November 2019