Northern England's disused mills 'at risk'

- Published

It's been a 30-year project to regenerate Halifax's Dean Clough Mill

There are regimented lines of workspaces beneath the beams and a thrum of machinery as over 1,250 workers go about their business in a Halifax mill. But this is not sooty Victorian England, rather the offices of a modern insurance firm with two million customers.

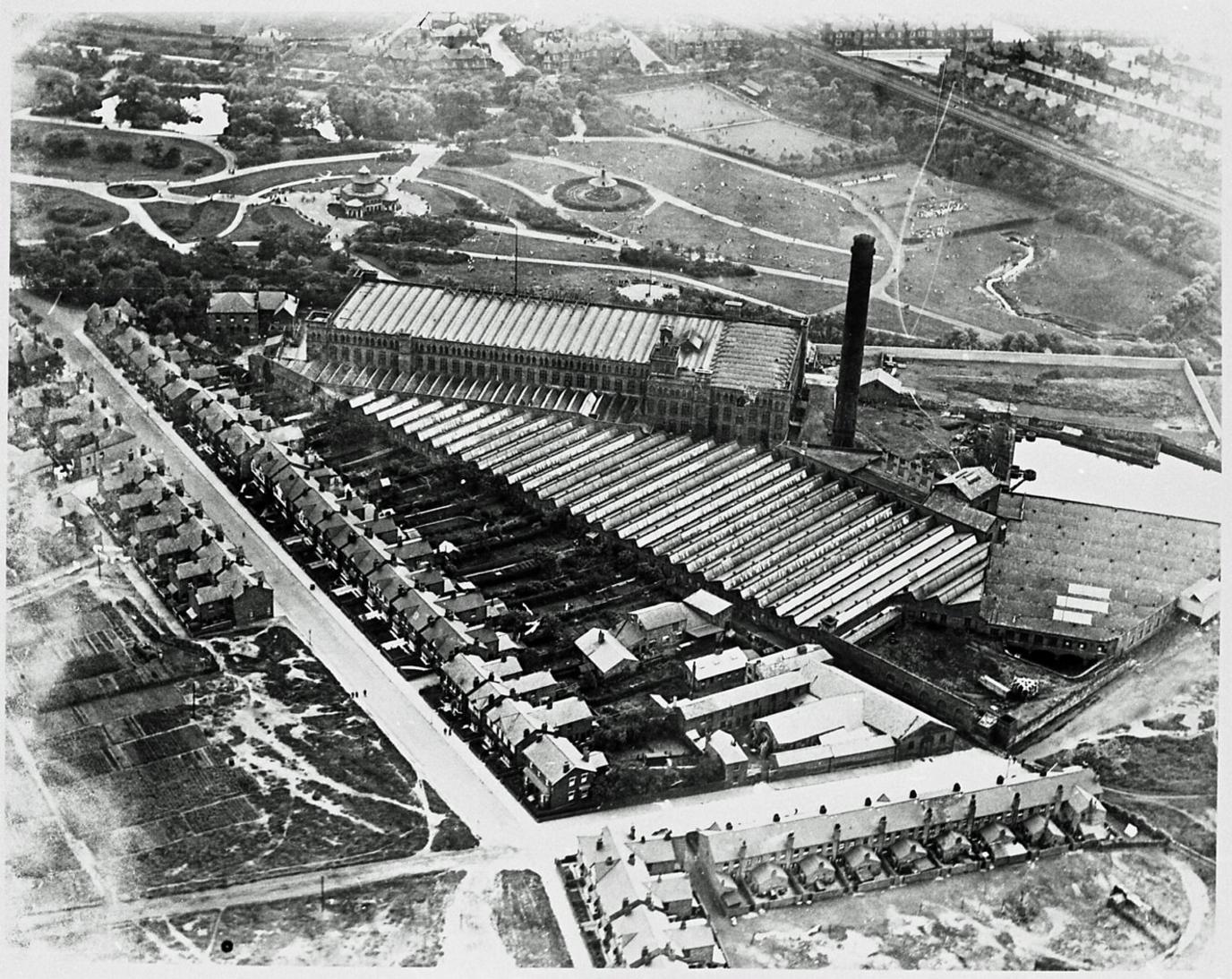

In the 1840s, Crossley's Carpets built the enormous 22-acre (9ha) Dean Clough Mill site to spin and weave its yarns. In its heyday it was one of the biggest carpet manufacturers in the world.

While the industrial decline was steady and final, there has been life in the old mill yet. "It's been about re-using elements one step at a time," explains chairman Jeremy Hall.

He and his father have spent 30 years, a lot of cash and taken a leap of faith with the mammoth site. They've reduced the mill buildings, from about a million square feet to about 600,000, whilst waiting patiently for the right tenants to come forward to fill spaces. It's worked: today it is bustling.

Dean Clough then and now: as a mill and as a modern office space

Dean Clough, external is one of almost 2,000 textile mills dotted across cities and towns in the Pennines. But research by Historic England shows well over a quarter of them are unused, and it that unless steps are taken to protect them, a significant part of the country's heritage will be lost forever.

"They say everything about the North West and West Yorkshire; it's the buildings, it's the skylines that we all know," says Historic England's regional director, Catherine Dewar.

Many of the 572 empty mills are often in the hearts of towns and well connected to local transport. They hold the potential for 120,000 homes or small business spaces without denting the greenbelt, in a region recently made big promises by the new Conservative government.

VIDEO: The challenge of restoring disused mills

But it's not all about potential economic prosperity.

"They tell the story of the local area," Catherine enthuses; from the neat lines of mill workers' houses, still loved and lived in, to the grand old bank buildings in town centres like Oldham or Rochdale, once counting revenues from these businesses.

"It's important to keep our heritage and everybody will benefit from that," she says.

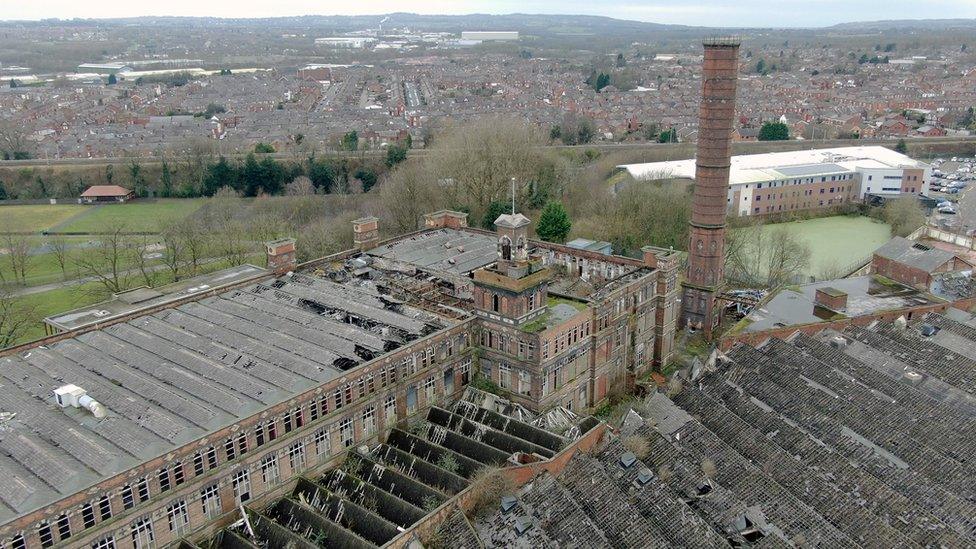

Others are trying, but almost 50 miles away, at Pagefield Mill in Wigan, regeneration feels a long way off. Once 1,300 workers span cotton here, now only pigeons circle the brickwork.

Pagefield Mill in Wigan in its heyday...

...and the disused mill now

The beautifully ornate chimneys loom over the fountains and pavilion in Mesnes Park as the West Coast mainline rushes by. The local college upped and left over a decade ago and hopes of redevelopment were dashed by a fire last year, external.

"Part of the challenge is finding a use that is cost-effective," says Marie Bintley, Wigan council's assistant housing director. "Clearly this is not the South East, where we have high land values."

The site is listed, and privately owned, but the council remains determined: "It's part of the fabric of the place, we want the community to celebrate this building," adds Ms Bintley.

Years of neglect have taken their toll: many windows are broken or missing, sections of the roof have caved in and rain pours in, seeping from floor to floor.

The council knows its time to rescue the building from demolition is running out: "We are in danger of coming to a tipping point where that becomes just too difficult," says Ms Bintley.

There are developers willing to rise to the challenges, but they're not run of the mill.

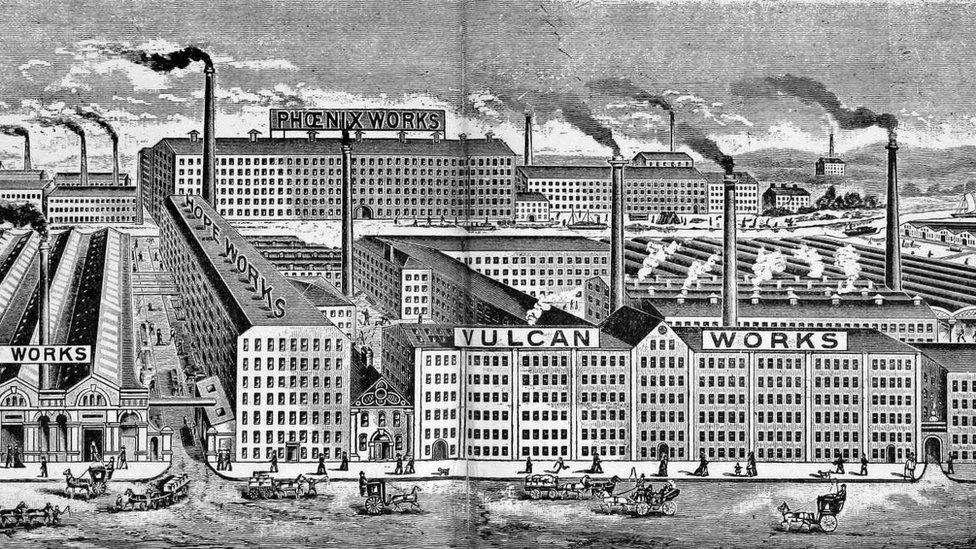

Manchester's Crusader Mill has been transformed...

...and has been turned into 123 apartments

Adam Higgins co-founded developers Capital and Centric; and Crusader Mill in the heart of Manchester is one of a clutch of older buildings his firm has taken on.

The reason is simple: "Arguably it's easier to build something from scratch. But it's quite difficult to put soul into a new block of flats, but you can do it quite easily in a building like this," he smiles.

It's taken five years from purchasing the site to almost completing 123 apartments, regularly unearthing unexpected damage. Just to make the whole project trickier for himself, Adam insists that no building will be sold to an overseas investor: each will be owner-occupied to retain that community the mill once housed.

That risk is worth taking, when you're within earshot of Manchester Piccadilly station. Trams hoot as they pass beneath the open window frames and the trendy bars of the city's Northern Quarter are but paces away.

Adam knows that the values drop off quickly for property as you move out of the city centre but he's also an optimist. "This place wasn't viable 15 years ago. It won't take long, as the North grows, for these economic benefits to reach smaller towns."

But it's time that's critical to save these historic sites: "I think [the] public sector does need to get involved, without it some buildings will just get worse and worse."

So are the mills really worth it? Back in Halifax they think so.

"It's been about re-using elements one step at a time," says Jeremy Hall in Halifax

Dean Clough's renaissance has been a slow burner, but now it's home to 150 businesses big and small - from multinationals to cosy cafes - and has even been immortalised in Lego.

Covea Insurance took on two mill buildings on the site in 2016, director Carol Geldard admits the business did see other office options - many of them cheaper - but says this wasn't a simple business decision: "We saw an opportunity to create a space that's fantastic for our people, but also to become part of a community doing something special, bringing a building back to life."

Next door, local lad Philip Crowther used to play amongst the rubble of the old mill site when his gran worked here.

When it came to picking a home for his flower business, his heart and head led him here: "There was a time when you could walk down to Dean Clough and get a job instantly. It's great now you're getting businesses, local and international, bringing new enterprise."

All agree that the mills' story is not over. And there is plenty more space, if others have the energy - and cash.