Reducing brain damage in sport without losing the thrills

- Published

Shona McCallin playing for the GB hockey team

When Olympic gold medallist Shona McCallin was hit on the side of her head by a seemingly innocuous shoulder challenge, she suffered what was originally thought to be a concussion.

However, headaches and other symptoms would not go away and brain scans revealed damage to her vestibular system - the part of the brain responsible for processing movement and motion.

It was seventeen months before she was able to play competitively again, but she made it back into the Great Britain hockey team.

"You know, unfortunately, injuries in sport and outside sport are a part of life," she says.

From football to F1, professional sport has become more aware of the impact it has on the brains of athletes.

The US National Football League (NFL) has acknowledged that it concealed the dangers of concussion from players, leading to a settlement with ex-players that is expected to cost the NFL more than $1bn (£800m) over a 65-year period.

The 2015 Will Smith film Concussion raised awareness of the impact collisions have on American Football players.

But damage to the brain is difficult to manage because it's difficult to measure. Often the effects are not felt until decades after players retire. So here is where new technology might help.

"In the NFL, they've put strain gauges into helmets to see what impacts are sustained - and they've been able to see the high amount of g-force exerted onto the helmet when two big players collide at speed," says Mr Ian Sabin, a consultant neurosurgeon from the Wellington Hospital in London who has worked with various sporting bodies, including the NFL.

US football players experience high g-forces during collisions

To help assess the impact of those collisions, the NFL, which runs American football, has entered a partnership with Amazon Web Services (AWS).

The organisations are working together on a digital platform that is fed by huge data inputs - including video analysis and sensor data from helmets.

The idea is to be able to create a digital representation of a player in a virtual on-field environment. The NFL can then simulate changes in the environment to see what would improve the safety of players.

The NFL makes the data available to firms that make helmets, and it says this has enabled improvements in one year that had previously taken a decade.

It has also launched a $3m helmet challenge for companies to design better helmets.

The platform could also be used in other sports such as soccer.

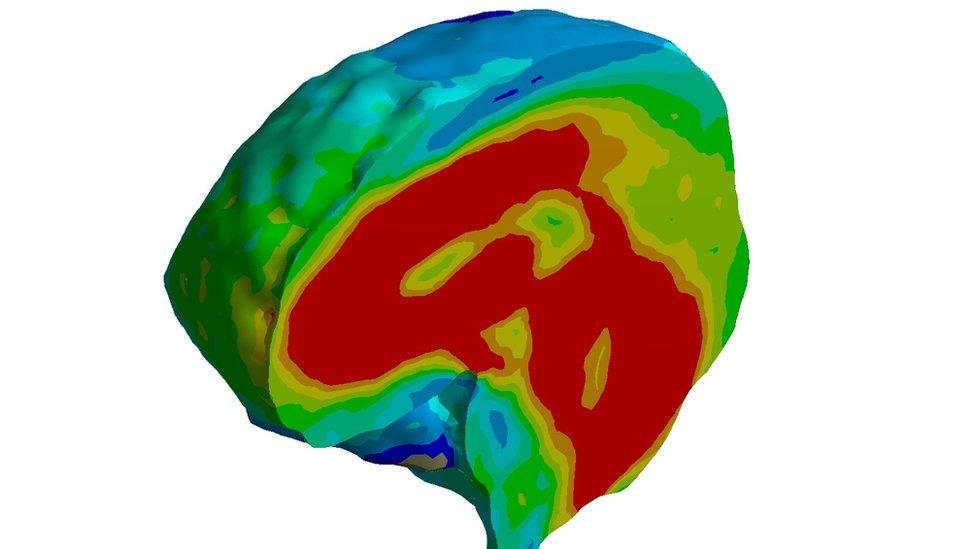

A picture of the brain 10 milliseconds after impact - high stress regions show up in red

This is where companies like ANSYS are pitching for business. It provides simulation technology to check there are no design flaws when creating a helmet for sports.

"We can create a computer model of your brain. As the geometry of the brain is so complex, we are using medical imaging and transforming that into a 3D model," Thierry Marchal, global industry director at ANSYS, explains.

Then the organisation can test and quantify the impact of certain actions, as well as validating these models with trained clinicians to ensure that the computer model represents and predicts accurately what's happening in a player's head.

"If there's some damage to a virtual player's head you can change a component such as the material to see if it will reduce the impact. Eventually we'll be able to have a helmet customised for specific athletes," he says.

Other technologies are being used for rehabilitation. For example, McLaren Racing uses MindMaze technology inside the helmets of F1 racing drivers to provide more accurate neurological data to improve diagnosis and treatments of brain injuries.

Despite the promise of these new technologies, Mr Sabin emphasises that there is still not a reliable imaging test that can either confirm a concussion, or tell the athlete whether they should stop playing their sport.

Football players have been reducing training sessions with headers

Having an extensive data set, such as the one NFL is putting together, could provide insight that hadn't been possible before, suggests Dr Willie Stewart. He is the consultant neuropathologist who led the study commissioned by the Football Association (FA) and the Professional Footballer's Association into the link between neurodegenerative diseases and ex-football players.

"We might consider something that hadn't been thought of before - it might be through using GPS tracking when players are accelerating, and how the brain functioning changes during that," he says.

Although technology is advancing at pace, it will take time to use these to prevent and reduce concussions and impacts to the head in sport.

In the meantime, sports bodies are taking action.

In a joint announcement in February, the FA, Scottish FA and Irish FA, advised that there should be no heading in training for primary school children, or under-11 teams and below.

There are also new rules for age ranges up until 18, with headers being kept a "low priority" and gradually becoming more frequent in training until the age of 16.

While much worthy research and development is going on, sports are often operating under financial pressure.

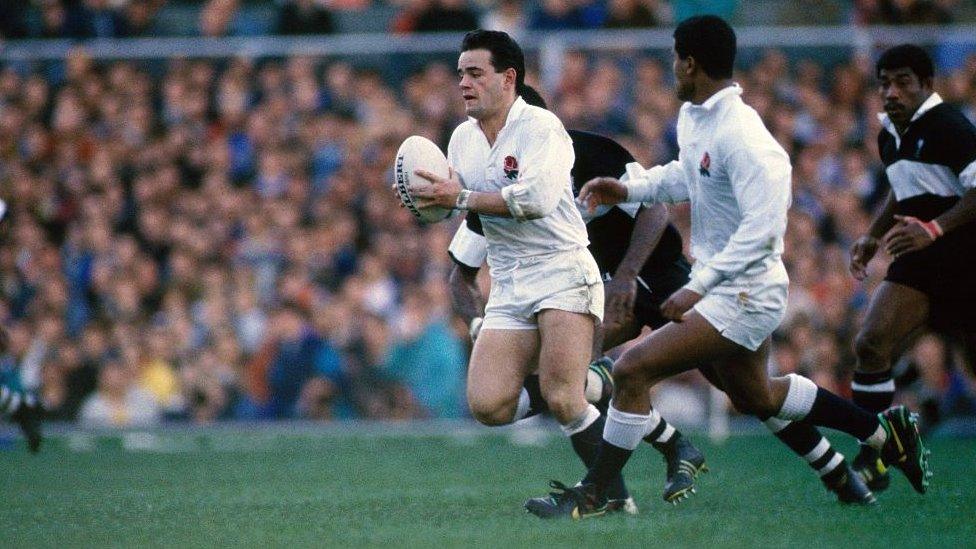

Will Carling playing for England in 1989

Will Carling, who captained England to three Grand Slams in the 1990s, says rugby union authorities are taking safety more seriously, but perhaps the biggest contribution to safety would be to play fewer games.

"I think sometimes we are still mistaking more games, for more money, for more profile, and we are abdicating a little bit of responsibility about player welfare.

"Exactly how much can the players at the very top of the game take? How much can their bodies and their minds actually sustain?"

Professional athletes like Ms McCallin have to accept the risks of their sport.

"For me, the benefits of sport, both on a spiritual, mental and emotional capacity really do outweigh the potential risks of injury," she says.