Stopping Venice choking on its own pollution

- Published

Locals are angry about the pollution from big cruise liners that come into the heart of the city

It is well-known that Venice is drowning as global sea levels rise because of climate change. Last year, the city suffered its worst floods in half a century.

Less well-known is that Venice is also choking on its own pollution.

Hundreds of diesel-powered vaporetti - commuter boats or water buses - spew out tonnes of carbon as they zigzag through the city's canals. Zipping to and from the Italian mainland, they ferry the 25 million tourists that visit annually, as well as food, hotel laundry and goods.

But some in this climate-challenged city believe they have at least a partial answer to Venice's environmental problems; an alternative vaporetto powered not by diesel but by hydrogen, a fuel that emits only water vapour when burnt and none of the carbon or greenhouse gases which cause pollution and climate change.

Commuter boats or water buses spew out tonnes of carbon as they zigzag through the city's canals

Still, this vaporetto won't be taking to Venice's waters anytime soon. In fact, its fate in some ways mirrors the problems that hydrogen has faced globally as an alternative source of "clean" energy.

For many decades, hydrogen has been known as the "magic molecule", the universe's most abundant element that could work as an alternative to natural gas and other fossil fuels. Concerns about hydrogen's safety and cost meant it never quite took off.

But with the threat of climate change now looming large, there are those who say its time has come, not least because the cost of making hydrogen using renewable energy - what's known as "green hydrogen" - has started to come down significantly.

This hydrogen-powered prototype is sitting idle as Italian law doesn't allow boats powered by fossil fuel alternatives to sail

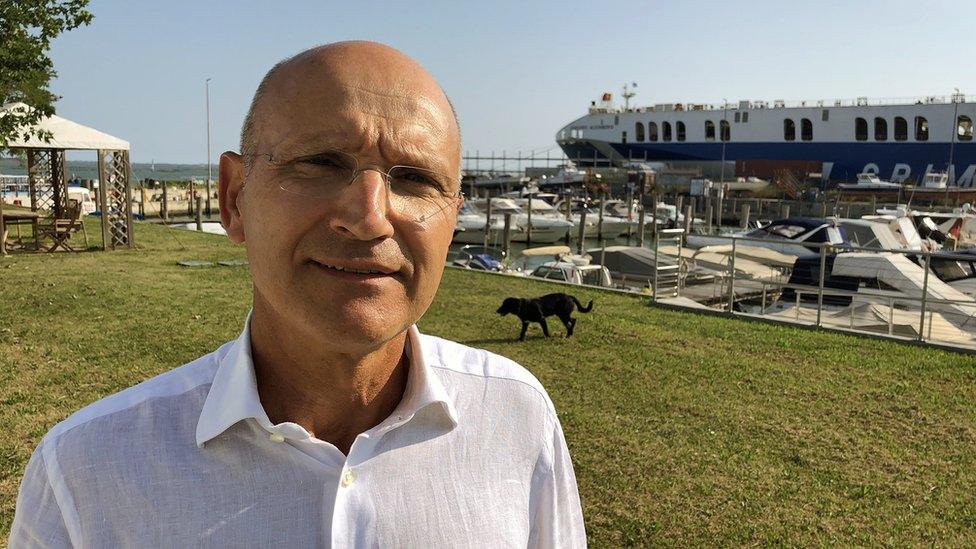

Among its evangelists is Marco Alverà, chief executive of Snam, the Italian company that operates Europe's largest natural gas pipeline network. Green hydrogen is a "key enabler for a decarbonised economy and [it's] becoming affordable," he says.

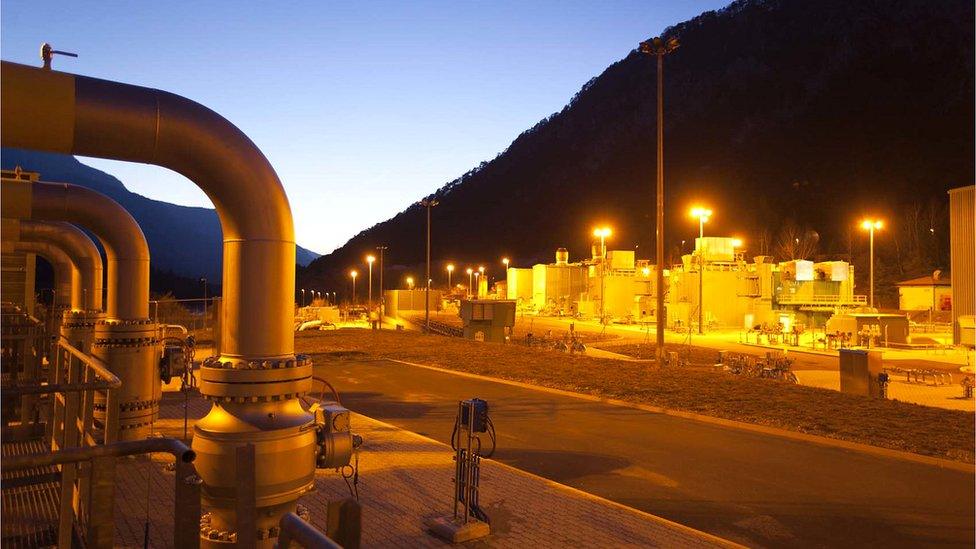

Last year, Snam injected a small amount of hydrogen into Italy's gas network, mixing it with natural gas. It was a much-publicised experiment to showcase hydrogen's potential - and convince the public it was safe.

But the company's vision is even more ambitious: Mr Alverà believes that one day huge banks of solar panels in north Africa could provide the energy needed to create green hydrogen which would then be piped into Europe through Snam's vast natural gas pipeline network.

In 2019, Snam injected a small amount of hydrogen into Italy's gas network to prove it was safe

People would use hydrogen instead of natural gas to heat their homes and cook. Green hydrogen would also power industry because it can generate the intense heat needed by industrial processes such as the manufacturing of steel and cement - industries which are otherwise difficult to de-carbonise.

With hydrogen, says Mr Alverà: "We have a path that doesn't bet on people changing their behaviour." And he reckons it wouldn't be too difficult for Snam's gas pipeline to be adapted to carry hydrogen instead.

But critics point out that the vast majority of all hydrogen being produced today is done so from fossil fuels, what's known as "grey" hydrogen. That effectively cancels out its environmental credentials. What's more they argue that adapting existing pipelines to carry hydrogen instead of natural gas is an expensive process.

Huge solar farms in north Africa could provide the energy for green hydrogen which would then be piped into Europe, says Snam

So what needs to change for hydrogen to really take off as a clean energy source?

The answer requires a quick chemistry refresher. To make hydrogen you need to split water, a process known as electrolysis. Water molecules are made up of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom (H2O). By adding an electrical current to water you separate them, getting bubbles of hydrogen and oxygen atoms splitting out.

"It's a very simple process. We've all done it at school," Mr Alverà says.

Electrolysis requires energy. Solar and wind power are now in many instances cheaper than fossil fuel energy which means that "suddenly you get a cost of [green] hydrogen that can really compete with other fuels in the economy," he says.

Green hydrogen is not competitive with green electricity, says renewable energy consultant Sauro Pasini

But Sauro Pasini, a consultant on renewable energy who has spent his career working in the Italian energy sector, isn't convinced.

"There are other options which remain more competitive [than green hydrogen]," he says. "I don't think hydrogen will play a role in [mitigating] the climate crisis in the near future." Mr Pasini notes that technology for green electricity - and its storage - is already many years ahead of hydrogen.

Snam's Mr Alverà remains undaunted. He concedes that electrification from renewables will play a significant role in decarbonising economies, rising to about 50% of all energy use.

Marco Alverà says the EU should help bring down the of green hydrogen

"The question is how do we make that remaining 50% carbon-free?" he says. He wants the European Union to put in place policies that would help bring down further the cost of electrolysers to make hydrogen competitive with fossil fuels.

It may all come too late for Venice's hydrogen-powered vaporetto. A prototype called the Hepic, is sitting idle in a shipyard outside the city because Italian law doesn't allow boats powered by alternatives to fossil fuel to sail.

"Of course I'm disappointed," says Fabio Sacco, the president of Alilaguna, the water bus company which runs Venice's vaporetti, and which developed the Hepic back in 2010 in a joint project with the regional authority of Veneto, at a cost of over one million euros ($1.1m: £850,000).

"Pollution is a big problem here - we're not going to give up," says Fabio Sacco

Delays in getting the Hepic approved to sail means the technology, and its commercial viability, remain untested.

"I would have liked to see the Hepic sail but the bureaucracy is slow and hasn't kept up," Mr Sacco says. "That said, pollution is a big and serious problem here in Venice and we're not going to give up."

Listen to more from Manuela Saragosa on BBC World Service's Global Business programme - Hydrogen: The answer to climate change?