Madam CJ Walker: 'An inspiration to us all'

- Published

Octavia Spencer stars in a new Netflix show about the life of Madam CJ Walker

When American journalist A'Lelia Bundles published her first article about her great-great grandmother, Madam CJ Walker in 1982, it was in the "lost women" column of a women's magazine.

That marked quite a comedown for Mrs Walker, who founded a haircare business that made her the country's first self-made female millionaire -"the world's wealthiest coloured woman, the foremost manufacturer and philanthropist of her race", as one newspaper described her when she died in 1919.

To this day, Madam CJ Walker products can be purchased in stores - an unlikely legacy for a woman who toiled in poverty for decades and whose parents had been enslaved.

But "for many years Madam Walker was just a little footnote in history. As a woman who made haircare products, she was really consigned to something trivial," says Ms Bundles, who published the first full-length biography of Mrs Walker, "On Her Own Ground" in 2001.

Now, however, Ms Walker is "having a moment", as Ms Bundles put it in a recent blog post.

Journalist A'Lelia Bundles is Madam CJ Walker's great-great-granddaughter, and her biographer

Her story can be found in some 200 books, she's been featured in several recent museum exhibits, including at the Simthsonian in Washington DC, and New York named a street in her honour last year. In March, Netflix released Self-made, a four-part series starring Octavia Spencer about her life and business, inspiring another publicity blitz - and the re-issuing of Ms Bundles' biography.

Meanwhile, her brand has been revived by Unilever subsidiary Sundial Brands, known for its SheaMoisture hair products, which bought the rights in 2013. The foundation started by Sundial's founder, Richelieu Dennis, has also bought her 34-room New York mansion, Villa Lewaro, with plans to turn it into a think-tank for black women entrepreneurs.

"So much of her story is unfortunately still timely," says Elle Johnson, one of the writers of the Netflix series, of the buzz. "When I look at her life and what she accomplished, I can't help but be amazed."

Born in Louisiana in 1867 as Sarah Breedlove, Mrs Walker was orphaned at age seven and a widowed mother by 20. Her struggles with hair loss - a common problem at the time due to infrequent washing - inspired her to start her business, the Madam CJ Walker Manufacturing Co in 1906, which sold a "treatment" that included scalp massage and a special ointment.

By 1916, she employed more than 10,000 agents and ran a network of schools that trained women to enter the hair industry - one of the few ways outside of domestic work that black women could make money at that time.

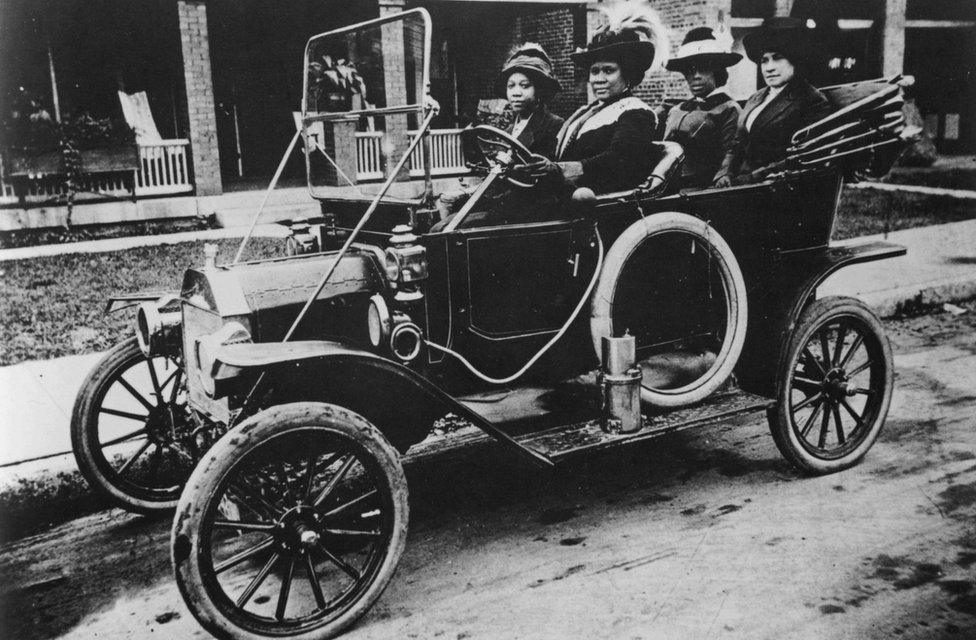

Madam CJ Walker behind the wheel in 1911

"I had little or no opportunity when I started out in life . . . I had to make my own living and my own opportunity," she later recounted, according to Ms Bundles' biography. "But I made it. That is why I want to say to every Negro woman present, don't sit down and wait for the opportunities to come, but you have to get up and make them!"

Ahead of her time

Mrs Walker - who renamed herself after marrying her third husband, with the Madam added for branding purposes - was part of a wave of black entrepreneurs that emerged in the decades after slavery to meet the needs of a black population largely ignored by white business.

That included other African-American women with major haircare businesses, such as Annie Turnbo Malone, whose products Mrs Walker sold before developing her own formula. Their rivalry - which Ms Bundles says is exaggerated for dramatic effect - is a central point of the new Netflix series.

But Mrs Walker - whose life also inspired a Duke Ellington opera - remains the best known. That's in part testament to her marketing savvy, including her willingness to stamp her products with her own image - standard fare in the age of social influencers but a bold move when white beauty standards ruled the day.

"There were so many things that we think we invented or came out of Harvard Business School and this is something that this woman was doing 100 years ago," says Nicole Jefferson Asher, one of the writers of the Netflix show. "It was her own innate business acumen."

A frequent public speaker, Mrs Walker also spoke out on political issues like lynching and described the mission of her company in terms of female empowerment. Her obituaries recognised her for her philanthropy as well as her riches.

"Today we talk a lot about social entrepreneurship and businesses having a double bottom line or triple bottom line, [maximising social and environmental good as well as profits]," says Tyrone Freeman, a professor of philanthropic studies at Indiana University, whose book about Mrs Walker's charitable work is due out this fall. "I see Walker doing this 100 years ago."

Unilever revived the Madam CJ Walker brand in 2013

Ms Asher says Mrs Walker's achievements made her a "folk hero" for generations of black women - even if she was often associated, incorrectly, with inventing the hot comb, a hair straightener.

But although her rags-to-riches tale seems made for the movies, until recently it was hard to get Hollywood to buy into stories focused on black stars, Ms Asher says, Now, at a time when America's economic divides are growing wider, racial and gender gaps are in the spotlight, and the power wielded by the country's business elite, through their companies and their philanthropy, is under scrutiny, the questions raised by her story resonate.

"This is a story about female entrepreneurship and the American dream and specifically the black American dream," she says. "The more we learn about history, about this time period, will help us get through the time period we're currently struggling in right now."

But Mrs Walker's story is compelling in her own right, she adds. "The example of that resilience and that determination and ambition really should be an inspiration to us all."