Swahili’s growing influence outside East Africa

- Published

Swahili is the national language of Tanzania, which is home to 59.7 million people.

There are over a hundred languages spoken in Tanzania, but Swahili is spoken by 90% of the nation and is what unites the country's 130 ethnic groups.

Swahili, which is known colloquially as "Kiswahili", is now used as the language of administration, and it is also widely used in schools and business.

The growing popularity of the language outside Tanzania in the last two decades has largely been catapulted by music, which is breaking down cultural barriers across the region.

In 2017, Tanzania became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to have an African language as the sole language of instruction in its schools, replacing English.

English is widely used in sub-Saharan African nations and is seen as being a critical tool for countries to be able to engage with the global economy, as well as enabling job opportunities and political development.

Following Tanzania's independence in 1964, children were expected to learn English in primary school, and then study Swahili in secondary school.

However, the Tanzanian government discovered that Tanzanian children did not seem to benefit from English lessons, and often could not hold conversations in English.

Teaching subjects in English actually led to lower academic performance in those subjects, so the government decided to make Swahili the sole language of instruction.

Swahili and the economy

However, there are concerns that using Swahili might not be as helpful in boosting Tanzania's economy as communicating in English would be.

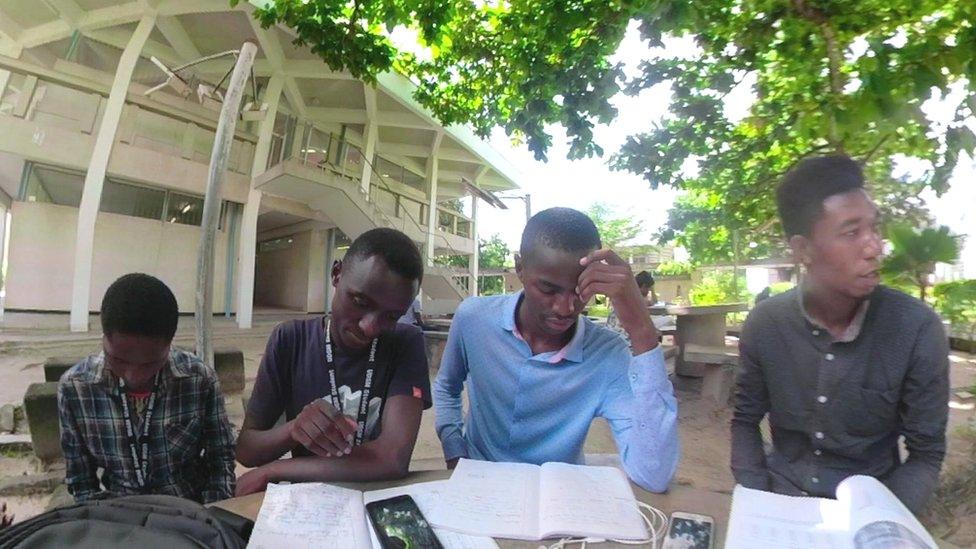

Students studying Swahili at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania

"It's something we can aspire to in the future, because I truly believe that when you talk about economic competence, you have to look at market share," Amani Shayo, a project manager at Empower Ltd, a Tanzanian firm specialising in recruitment, outsourcing and training told the BBC.

"But in the space we currently have, where most of the companies are multinationals, they operate on a global scale and the means of communication is English."

In order to access new markets both abroad and in Tanzania, Mr Shayo believes that being able to speak English is still key at the moment.

Yet universities around the world have introduced Swahili as a language of study, and South Africa is now bringing the language to its schools.

Swahili is also the only African language to have been officially recognised by the African Union, which shows that it is gaining in prominence.

"If you don't have a common language, it's difficult to do business. I call the language a product, because we need to publish more books and prepare more Kishwahili teachers," said Dr Ernesta Mosha, director of the National Institute of Kiswahili at the University of Dar es Salaam.

She thinks that Swahili will truly be able to flourish as a common language with the expansion of the publishing, education and translation sectors.

- Published1 March 2020

- Published4 June 2019